Two by Austin Pendleton: BOOTH and ORSON'S SHADOW

BOOTH by Austin Pendleton

role: Junius Brutus Booth

Another backstage tale by Austin Pendleton. Based on the true story of Junius Booth, a tormented, alcoholic, 19th-century actor. His glory would be forgotten, while son Edwin would win fame as a great actor and his other son, John Wilkes, would win infamy as Lincoln’s assassin. “As the twig is bent, so grows the tree …”

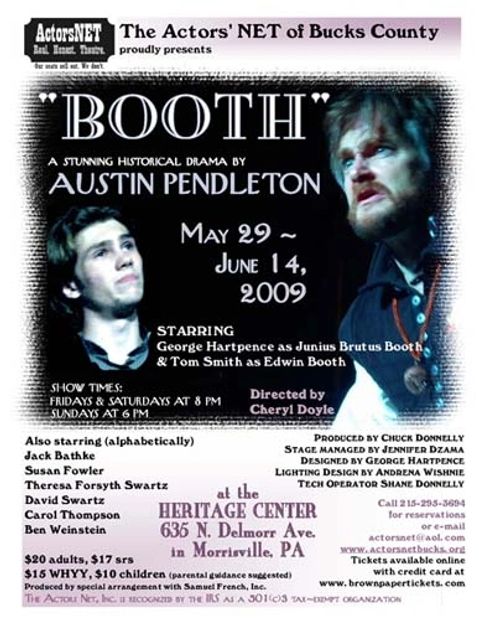

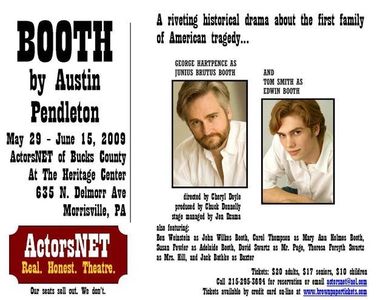

ActorsNET of Bucks County production

May 29 - June 14, 2009

Directed by Cheryl Doyle

Produced by Chuck Donnelly

Stage Managed by Jennifer Dzama

Set design by George Hartpence

CRITICAL PRAISE

"Director Cheryl Doyle gets everything she can from her cast, while smoothly changing the pace from dramatic to comedic and back to dramatic."

Tuesday, June 9, 2009

By Anthony Stoeckert

The Princeton Packet

"In playing Junius, George Hartpence gives another of his terrific performances. Junius’ unpredictable behavior transitions abruptly but convincingly from humorous to frightening. Throughout, Hartpence maintains a sense of humanity. I never doubted that Junius loves his family; he just can’t put them before himself or his craft."

Tom Smith holds his own while sharing the stage with Hartpence. Other terrific work comes from Carol Thompson as Mary Ann Holmes, the mother of the boys. Susan Fowler shows up toward the end as Adelaide, the wife Junius left behind, but she makes the most of her time on stage, and her character has a definite impact on the lives of the others.

It’s playing at the Heritage Center through June 14, and it deserves to be playing to packed houses for the rest of its run.

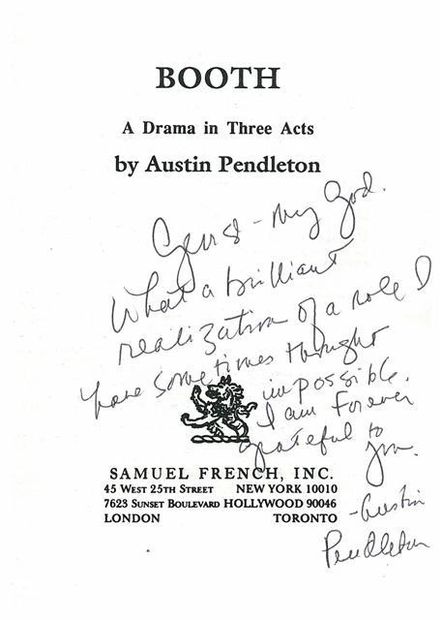

Actors’ NET Testimonial from Actor/Director/Playwright Austin Pendleton

via email dated July 17, 2009

“On June 7 of this year (2009) I traveled with some friends to see a production by Actors' NET of my play Booth. They were doing a version I had last seen in 1994, the one published by Samuel French, and I had since done a couple of rewrites of the play, trying to find an ultimate form for it, but haunted by the feeling that I had strayed from the heart of it in the process. The production of Actors' Net brought me back to that heart. I saw, in the passion and depth of what they found in the play, what I had lost in it and therefore I saw so clearly the revisions I could make to clarify the form of the piece in a way that protected that heart. It was a transformative experience for me seeing their work. They had done another play of mine earlier in their season and I had heard splendid things about what they did. Booth, however, was a vast challenge for them because it has always been a play in search of itself. Actors'Net, through the beauty of the direction and acting they bestowed upon the play, helped it very far along in its search. I am forever grateful. They are to be cherished and nurtured. They, to me, are what theatre is all about.”

Booth Summary

excerpted from Ben Brantley's 1994 NYTimes review of the York Theater Company production at the Midtown Arts Common at Saint Peter's Church, Lexington Avenue at 54th Street, Manhattan.

Austin Pendleton's psychodrama “Booth” - about the legendary theatrical family of the 19th century - portrays Junius Brutus Booth, an alcoholic star in the last years of his career, a man who comes across as a cataclysmic force of nature, whose every gesture seems freighted with the potential for devastation.

Mr. Pendleton's script has endowed Junius with all the traits common to fictional portrayals of narcissistic scenery chewers -- overweening vanity, mesmerizing charm, territorial paranoia and blazing physical energy – but they are here pushed firmly over the edge of madness. This is a man, after all, who once played Othello naked and came close to smothering Desdemona in the bedroom scene.

A particular strength of Mr. Pendleton's script is that it is able to suggest both Junius's uncontrollable compulsions and an abiding melancholy awareness of their effects. When, in the play's first scene, it is decided that Edwin will accompany his father on a tour as a dresser, Junius warns him that he will destroy him on the road. And at a later point, he tells him: "The worst has happened. I have fascinated you." In this case, self-knowledge is in no way redemptive.

The play was inspired by the real-life history of the Booth family. Junius Booth, a British actor who appeared with (and felt humiliatingly overshadowed by) Edmund Keane in London, immigrated to America, leaving his wife and young son behind. In this country, he took a mistress by whom he fathered many children (two of whom, Edwin and John Wilkes -- who would later become the assassin of Abraham Lincoln -- are represented here). And he made a career of bringing Shakespeare to the still largely rustic new nation. While alternately dazzling and contemptuously attacking his audiences in manic outbursts, he always kept, as Edwin finally tells him in disgust, "your actors backstage, your wife in London and the mother of your children in the backwoods."

For much of the play's first half, it comes across as a dark-edged, often-witty celebration of the thespian's disjointed world, a sort of historical variation on David Mamet's "Life in the Theater," with a neophyte on the road learning from an eccentric seasoned ham. In these sections, for all of Junius's violent extravagance, he seems like a cousin to the alcoholic swashbuckler portrayed by Peter O'Toole in "My Favorite Year," who charms more than he alarms us. "Sit still, idiots!" Junius is heard yelling at the audience. "In five minutes, I'll give you the damnedest Richard you've ever seen."

But as the tour progresses, and Edwin begins to develop his own, independent theories of acting, the play shifts into a darker Oedipal struggle from which there can be only one survivor. It takes the form of both Edwin's attempt to make his father come to terms with the consequences of his irresponsibility -- of the lives he has wrecked among his family and the people he works with -- and his gradual usurpation of his father's role as a matinee idol.

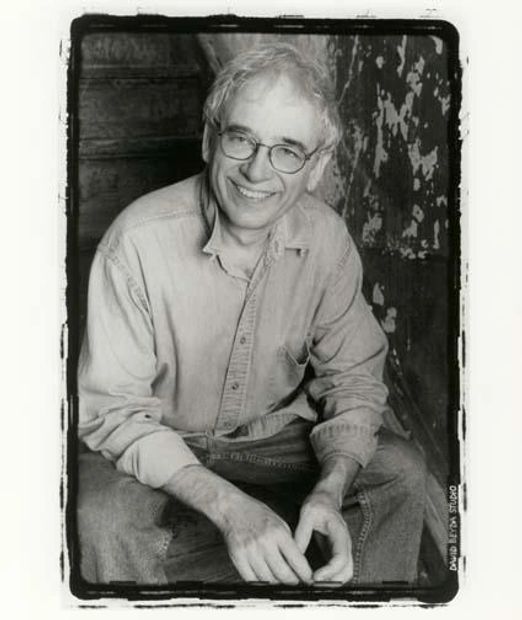

About the Playwright

AUSTIN PENDLETON (Playwright)

A graduate of the Yale School of Drama - is an acclaimed multi-talented artist.Booth is one of his three published plays - a second, Orson's Shadow, was presented at ActorsNET for a Jan/Feb run, and his third, Uncle Bob, is under consideration for future presentation. For more information about the ActorsNET production of Orson's Shadow, refer to my web page . Mr. Pendleton co-wrote the book for the musical The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz with Mordecai Richler; music by Alan Menken and lyrics by David Spencer. An ensemble-member of Steppenwolf Theatre since 1987 he apprenticed at the Williamstown Theatre Festival, where he frequently acts and directs. On Broadway, he has appeared in The Diary of Ann Frank, Doubles, Hail Strawdyke and as Motel in the original cast of Fiddler On the Roof.AnObie award -winning actor, Mr. Pendleton just completed an Off-Broadway run of The Mad Monk (Jan `09). Other Off-Broadway acting credits include Richard II, Richard III, Hamlet, The Sunset limited, The Sweet Days of Isaac, and Oh, Dad, Poor Dad, Momma's Hung You in the Closet and I'm Feelin' So Sad. Regional acting credits include King Lear and Waiting for Godot for the New Repertory Theatre.Film credits include The Front Page, Piccadilly Jim, Dirty Work, Finding Nemo, A Beautiful Mind, Queenie in Love, Manna from Heaven, Mr. and Mrs. Bridge, What’s Up Doc, Joe the King, The Associate, Trial and Error, Amistadt, Sue, The Muppet Movie, My Cousin Vinnie)' and Christmas with the Cranks. His television credits include Homicide (NBC), 0Z (HBO), The Fourth Floor (HBO) and Liberty (PBS). He has directed three Tony-nominated Broadway productions: Spoils of War by Michael Weller and starring Kate Nelligan, The Little Foxes by Lillian Hellman and starring Elizabeth Taylor, and the musical Shelter by Gretchen Cryer and Nancy Ford, which starred Marcia Rodd. He teaches acting at the HB Studio in New York City, where he lives. In 2009 Pendleton directed Uncle Vanya by Anton Chekhov at the Classic Stage Company in the spring of 2009, Pendleton starred in an off-Broadway production of Love Drunk written by Romulus Linney.

Austin Pendleton on "BOOTH"

"It was at Yale that he first started writing the book for college musicals, in particular for one about Edwin Booth, great American actor (1833-1893); it won a Yale Drama competition and, says Austin, “kicked around for years as a musical done here or there; then one day somebody said: ‘You should turn it into a play,’ so I did. I wrote it, my first play, as a 50th birthday present to myself” – a play simply called “Booth” – “and it was done at Williamstown, at the Long Wharf (in New Haven), and by the York company here in New York; a great success every time, mainly due to a spectacular performance by Frank Langella in all three productions.”

Austin Pendleton at ActorsNET

Playwright's inscription in my script

Grab interest

Say something interesting about your business here.

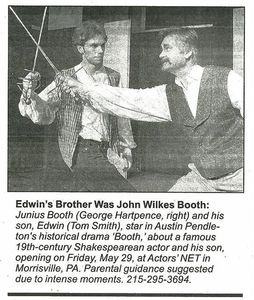

US 1 newspaper promo article

Interview with Austin Pendleton for Princeton Packet

I think this photo really shows the intensity of the relationship between this father and son... It comes towards the end of Act II, after Junius and Edwin have

practiced the duel from Richard III, and Junius has tried several dirty tricks to get the upper hand, exasperating Edwin.

BOOTH - Act I

Tom Smith as Edwin Booth

The Booth Family

Junius Brutus Booth and Edwin Booth

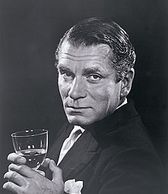

Junius Brutus Booth

Mary Ann Holmes

Edwin Booth

John Wilkes Booth

BOOTH - Act II

Junius chastized Edwin for assuming the role of Ratcliff against his express orders.

BOOTH - Act III

Junius (George Hartpence) arrives backstage at Edwin's (Tom Smith) Hamlet performance

Booth Family Timeline

Jackson Papers Project Helps Solve History Mystery

subtitled: "As the twig is bent, so grows the tree - Part 2"

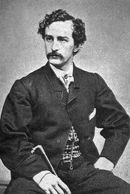

The Andrew Jackson Papers Project at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, has helped solve the mystery surrounding a letter threatening the assassination of President Andrew Jackson.

The mystery centers on a July 4, 1835, letter received by Jackson and signed by Junius Brutus Booth. London born Booth was a flamboyant Shakespearean actor of the day and manic public figure -- and father of John Wilkes Booth, who would assassinate President Abraham Lincoln 30 years later, in 1865.

The letter, kept in the Library of Congress, says:

To His Excellency, General Andrew Jackson, President of the United States, Washington City,

You damn'd old Scoundrel if you don't sign the pardon of your fellow men now under sentence of Death, De Ruiz and De Soto, I will cut your throat whilst you are sleeping. I wrote to you repeated Cautions so look out or damn you. I'll have you burnt at the Stake in the City of Washington.

Your Master, Junius Brutus Booth.

You know me! Look out!

Dan Feller, history professor and director of the Andrew Jackson papers project, said presidential historians always believed the letter to be a hoax. But a recent investigation, involving Feller and his staff, the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Ill., the Hermitage in Nashville, the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., and others, has proven the letter authentic.

Feller said there are several reasons why presidential historians were convinced the letter was a fake.

First, someone -- presumably one of Jackson's clerks -- wrote "anonymous" on the envelope. Historians believe that notation meant Jackson's own staff considered the letter to be a fake.

Also, the letter indicates that Booth had written to Jackson on several occasions before, but there is no other known correspondence between the two.

Finally, Feller said, it was understandable that someone writing such an inflammatory letter might forge Junius Booth's name to it.

"Booth was sort of a combination of Dennis Rodman and Darth Vader," Feller said. "He was a famously histrionic character. Signing his name as an alias wouldn't be at all illogical."

America's seventh president had become accustomed to threats, according to Robert V. Remini, author of the biography "Andrew Jackson" and history professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

"It wasn't a crime to threaten the life of the president back in Jackson's time," Remini said.

Loved by the masses, Jackson also was considered by some to be unfit for the presidency. A man named Robert Lawrence tried to assassinate Jackson earlier in 1835.

"He approached Jackson on the steps of the Capitol, but the gun misfired," said Marsha Mullin, vice president of museum services and chief curator at the Hermitage, Jackson's Nashville home.

The Tennessean then chased Lawrence with his cane.

"His forceful personality was such that it attracted the crazies of the world," Remini said of the same incident.

While presidential historians dismissed the letter as a fake, theatrical historians assumed it was real. The historians' debate might have gone unnoticed if the Lincoln Museum in Springfield hadn't put a copy on display as if it were authentic.

A visitor saw it and, later, while visiting the Hermitage -- Jackson's home in Nashville -– began asking questions about the letter and its veracity.

The Hermitage staff called Feller, and he called the staff of the Lincoln Museum.

Feller hoped to quash rumors that the real Booth was the author. He was in for a surprise when he researched the return address on the envelope, Brower's Hotel in Philadelphia.

They found records showing that Booth was in a theater production in Philadelphia in July 1835 and coincidentally had called in sick on July 4 -- the day the letter was written.Further, they discovered that he always stayed at the Brower's Hotel when he was there," Feller said.

In a letter to his theater director, Booth apologized for not showing up for a performance - the same day the Jackson letter was written.

"He later apologized (to the director) for writing letters that he shouldn't have, including letters to 'authorities of the country,' Feller said.

A handwriting analyst confirmed that the handwriting matched that of other surviving Booth papers.

As for the motive behind Booth's threat?

In the letter, Booth demands clemency for two men sentenced to death for piracy for robbing an American ship of $20,000 in coins and attempting to kill the crew.

It was a very celebrated case of the day and many people thought the pirates -- who claimed they were slave traders and not pirates, but weren't given time to procure evidence to prove it -- had gotten a bum rap, Feller said.

"It had all of the elements of the O.J. Simpson trial," he said. "Vivid personalities, allegations of authorities' misconduct, over-the-top lawyers, disputed evidence, etc."

In addition to all of this, Feller said, Jackson was quite controversial and some of his decisions -– such as his patronage policy, Indian relocation and banking changes -– were highly criticized.

"Jackson was a famously polarizing figure in his own day," Feller said.

- excerpted from University of Tennessee Knoxville website article

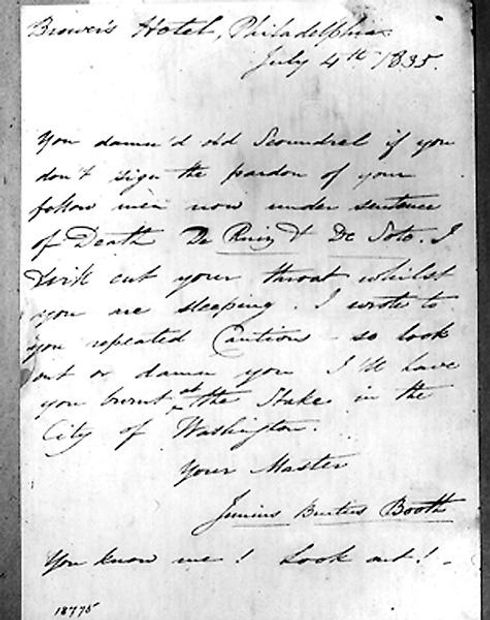

ORSON'S SHADOW by Austin Pendleton

role: Laurence Olivier

Directed by Cheryl Doyle

produced at the ActorsNET of Bucks County

January 23 - February 8, 2009

featuring:

Dale Simon as Orson Welles

George Hartpence as Laurence Olivier

Paul Dake as Kenneth Tynan

Carol Thompson as Vivien Leigh

Vicky Czarnik as Joan Plowright

Mark Riley as Sean, the stagehand

Technical Credits:

Stage Management by Dennis McGuire

Assistant Stage Manager & Box Office by Lorraine Murray-Robson

Lighting Design by Andrena Wishnie

Set Design by George Hartpence

Critical Praise for the ActorsNET production of Orson's Shadow:

excerpts from Theater Review by Anthony Stoeckert in The Princton Packet

‘Orson’s Shadow’

The collaboration between Orson Welles and Laurence Olivier is examined in this solid Actors’ NET of Bucks County production

Wednesday, January 28, 2009 6:24 PM EST

By Anthony Stoeckert

"George Hartpence (who also designed the simple but moody sets) makes a fine Olivier, behaving so differently than you’d think a legend would. He’s incapable of making a decision without Plowright and is fearful of trying anything new. He’s most afraid of telling Vivien, who is mentally ill, that he wants to end their marriage. A phone call between Olivier and Leigh is one of the play’s most dramatic. Hartpence displays a desperation to get away from Leigh while making it clear that although he may love Plowright, he loves Leigh more, he just can’t handle the illness anymore."

"Carol Thompson is terrific as Leigh, the play’s trickiest part. She acts affected, as a mentally unstable star would, while keeping everything believable and true."

"Playing Plowright is Vicky Czarnik, who’s very good at playing the kind of woman who would offer comfort to Olivier. It makes perfect sense that he would seek her advice and listen to it."

"Actors’ NET deserves praise for bringing different works to the area, and for doing a fine job with Orson’s Shadow."

Interview with playwright Austin Pendleton on “Orson’s Shadow” which opened on January 23rd, 2009 at the ActorsNET of Bucks County

Austin Pendleton: I’m so thrilled that the ActorsNET is doing two of my plays, Orson’s Shadow and Booth, in their season.

In the spring of 1996 I was approached by my friend Judith Auberjonois to write the play and it was developed at Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago. Over breakfast that morning she told me that in 1960, in London, Orson Welles had directed Laurence Olivier and that by the time the play opened Orson no longer felt welcome in the project.

Orson’s Shadow re-imagines actual events during those rehearsals of Eugene Ionesco's Rhinoceros, directed by Welles and starring Olivier and Joan Plowright (his then paramour and soon-to-be third wife). Having Welles direct the play was set in motion by Welles' ardent admirer, critic Kenneth Tynan for whom this matchmaking was a stepping stone to a job as the soon to be formed National Theatre's literary manager, which Olivier had been named to head. Additional theatrical fireworks ensue with visits from Vivien Leigh (Olivier’s soon-to-be ex-wife).

AP: I was daunted by the idea at first. Originally I wasn't sure how to approach their lives so that they would seem more than "turf wars," but then I read in a biography of Olivier that it was during the rehearsals for Rhinoceros that Olivier decided to make the break with Vivien Leigh and that's when it fell into place. I knew there was something dramatic there.

AP: I think that these characters are all on the line. Playwrights are drawn to people, whether imaginary or actual, who do that. Who wants to watch an evening of people who don't put themselves on the line? They allow themselves to be totally vulnerable and I like that.

AP: Almost everything in the play is based on fact, although things happen not necessarily in the context in which they originally took place.

AP: I had worked with Orson in the movie of Catch-22, which was rough. He was an unhappy guy and wished he had been directing it. He was very funny and charismatic, but disruptive. He did to director Mike Nichols on that film what Olivier does to Orson in Orson's Shadow. After that movie I began to see his other movies and I saw that he was a major artist.

AP: I also met Vivien Leigh once for about an hour in 1962. I never saw her on stage, but I was in Oh Dad, Poor Dad and she was thinking about doing the show in London. My mother and I were invited to tea by Vivien so that we could talk about the play. We went up at 4 PM to Vivien's suite in the Dorset. She was gorgeous, in part because she was in distress (this was a couple of years after the breakup with Laurence) in that way that with some people their beauty is enhanced by suffering, it just intensifies their beauty. She's the only person I ever met where there was a kind of courtesy that is rarely seen.

You're an actor, playwright, director and you wear many hats very well. When did you start writing as a playwright?

AP: When I turned 50. It was my present to myself. Until then I had been hired to work on the librettos for musicals, but none has been produced professionally. And then someone said, why don't you just try writing a play? I took the idea behind a musical I had been working on and I turned it into my first play, Booth. It was very exhilarating and that play was a real crowd-pleaser.

Booth, another theatrical story - this time about the famous first family of American Tragedy - is scheduled for a May/June run in 2009 at the NET. With any luck, the ActorsNET will complete the trilogy by presenting the third of my plays, Uncle Bob (which by the way has nothing to do with famous theatrical personages), in an upcoming season soon.

Excerpted with the playwright’s permission from an interview with Warren Hoffman, dramaturg for the Philadelphia Theatre Company, and from other direct communications with ActorsNET personnel.

ORSON'S SHADOW CAST and Promotional Materials

ActorsNET final production poster

ORSON'S SHADOW - Act I

Paul Dake as Kenneth Tynan welcomes the audience and sets the stage.

ORSON'S SHADOW - Act II

George Hartpence as Laurence Olivier and Vicky Czarnik as Joan Plowright

ORSON'S SHADOW - Act III

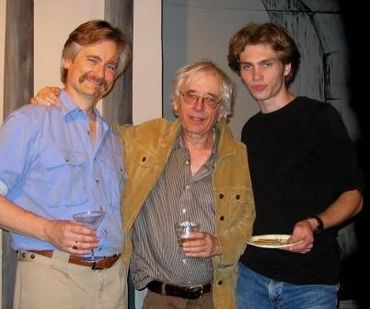

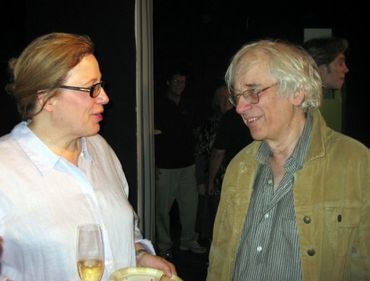

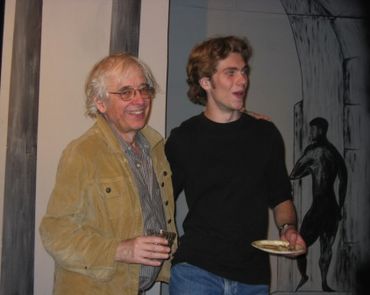

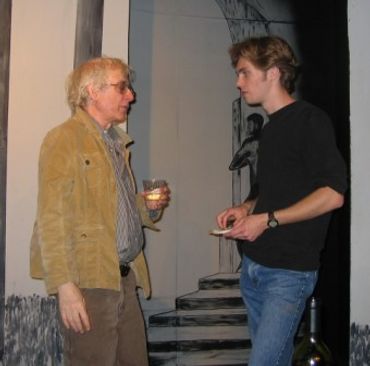

Glitterati

Vivien Leigh (1913-1967)

Laurence Olivier (1907-1989)

Laurence Olivier (1907-1989)

The daughter of British colonials, Leigh was born in Darjeeling, India and later moved to Europe for her schooling. Leigh was featured on the London stage in productions of Shakespeare's Richard II (1936) and A Midsummer Night's Dream (1937) before her star-making turn in film as Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind (1939). In 1940, Leigh married Laurence Olivier and the two actors quickly became prominent celebrities in the theatre world and toured together abroad in productions of The Skin of Our Teeth, The School for Scandal, and Richard III in 1948. Leigh returned to film on occasion, starring in That Hamilton Woman (1941), Anna Karenina (1948), and A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) as Blanche DuBois - a role originated by her in its London debut and which garnered her second Academy Award.However, Leigh's personal problems at times disrupted her professional success. In 1945, while acting with Olivier in The Skin of Our Teeth, she suffered from the beginnings of tuberculosis - a disease which would ultimately cause her death.Another complication was Leigh's long struggle with manic depression and bipolar disorder, which perpetuated rumors of her difficult behavior on the set and in rehearsal. In the last few years of her life, Leigh made her final film, Ship of Fools (1965), and performed in Chekhov's Ivanov on the New York stage in 1966.

Laurence Olivier (1907-1989)

Laurence Olivier (1907-1989)

Laurence Olivier (1907-1989)

Born to the son of an Anglican minister in a London suburb, Olivier studied theater as a child and made his professional debut with the Birmingham Repertory Company in 1926. Olivier became most famous for his interpretations of Shakespearean drama and his major stage plays included Hamlet, Othello, Richard III, Antony and Cleopatra (also starring Vivien Leigh), and The Entertainer. He won Academy Awards for his screen version of Hamlet in 1948 (Best Actor and Best Picture). He was knighted in 1947 and elevated to the rank of baron in 1970. In 1936, Olivier first worked with Vivien Leigh in the film Fire Over England. The two soon fell in love and were married in 1940 and became a power couple in the theater until their divorce in 1960. In 1963, Olivier became the director of the National Theatre and stayed there until 1973. In 1974, Olivier was diagnosed with dermatomyositis, a muscle-crippling disease that limited the amount of acting that Oliver could take on. Some of Olivier's most famous films include: WutheringHeights(1939), Hamlet (1948), Richard III (1955) Spartacus (1960), Sleuth (1972), and Marathon Man (1976). He published his autobiography Confessions of an Actor in 1982.

Orson Welles (1915-1985)

Laurence Olivier (1907-1989)

Kenneth Tynan (1927-1980)

Welles was born to a successful inventor (father) and concert pianist (mother) in Kenosha, Wisconsin. By the age of fifteen, both of his parents had passed away, leaving Welles with a large inheritance, which gave him the freedom to explore his artistic talents. In 1931, Welles became a member of Dublin's Gate Players, and during the 1930s, Welles worked with John Houseman on the Federal Theatre Project, which led to the formation of the Mercury Players. In 1938, Welles's broadcast of H.G.Wells's War of the Worlds on the radio was so convincing it struck actual fear into the American public, who believed it was a real account of an alien invasion. In 1941,Welles directed, co-wrote, and starred in Citizen Kane (1941), one of the most acclaimed films of all time. However, budget and production problems damaged Welles's reputation at RKO and his contract was terminated. Some of Welles's theatrical credits as director include: Macbeth (1936), The Cradle Will Rock (1937), Native Son (1941),Othello (1951), and King Lear (1956). Notable film credits include: The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), Jane Eyre (1944), The Lady from Shanghai (1948), which co-starred his former wife, Rita Hayworth, The Third Man (1949), Touch of Evil (1958), and Chimes at Midnight (1966).

Kenneth Tynan (1927-1980)

Kenneth Tynan (1927-1980)

Kenneth Tynan (1927-1980)

Tynan was born illegitimately in Birmingham, England. He wrote his first review at the age of 16 and went on to Oxford where he honed his writing skills. Upon graduating, he quickly entered the professional field of dramatic criticism where he became one of the most feared and respected critics of London theater. Tynan began working for The Spectator in 1951, and then moved on to The Evening Standard and The Observer, becoming the latter's critic at the young age of 27. He remained at The Observer until 1958 when he came to New York to become the drama critic for The New Yorker. Tynan played a key role in establishing the National Theatre which opened in 1963 and served as the theater literary manager for nine years. Tynan himself also wrote three plays including the erotic revue Oh, Calcutta! (1969), which became one of the longest-running Broadway musicals. Tynan died at the age of 53 from pulmonary emphysema in Santa Monica, California and was survived by his wife Kathleen and three children.

Joan Plowright (1929 - )

Kenneth Tynan (1927-1980)

Joan Plowright (1929 - )

Plowright was born in Brigg, in Lincolnshire, England, to a dancer/actress and a newspaper editor. She first appeared on the professional stage with director Harry Hanson's theater company at the Savoy. She later attended the Old Vic Theatre School in London. After an unsuccessful marriage to Richard Gage in 1953, the actress began an affair with Sir Laurence Olivier, whom she had met while performing The Entertainer (1957). In 1961, the couple married and had three children together. Other famous theater credits include an adaptation of Moby Dick--Rehearsed (1955), directed by Orson Welles; Look Back in Anger (1956); Ionesco's The Chairs and The Lesson (1956), The Country Wife (1957); A Taste of Honey (1961) for which she won a Tony Award; and Chekhov's Uncle Vanya (1962), co-starring Olivier. Her film credits, among many others, include Enchanted April (1992), Jane Eyre (1996), and Tea with Mussolini (1999).

Notes from Austin Pendleton and more...

Playwright's advice on playing Laurence Olivier:

(above: George Hartpence as Laurence Olivier & Vicki Czarnik as Joan Plowright)

Mr. Pendleton was kind enough to reply to a letter I sent to him asking for advice on assaying the role of "the greatest actor of the twentieth century." His advice proved invaluable to me. GH

"Advice: well, I guess, just go for it. Remember about Olivier: he's not an asshole. (Some people seem to miss that point.) In a way he's the most professional of all of them because he's really tearing himself apart trying to find his way into the part he's playing. And he does love Vivien, he really does. It's just that she scares the shit out of him. It's implied but never directly stated in the play (and perhaps it should be) that he's the only one of the five of them in the play to whom success did not come easily and early (poor Sean is, of course, in another category altogether). So he (Olivier) desperately doesn't want to piss it all away. What today we would call the bipolar state (Vivien certainly, and to a certain degree Orson and Ken) is terrifying to him, though (and because) he has more than a trace of it in himself. He keeps watching it destroy other people, as people and as artists and as professionals, and, by God, that is not going to happen to him."

My Two Cents by George Hartpence: Resources for studying Olivier

"I never pass along my secrets. Never." Larry to Joanie in Orson's Shadow

But I do.

I used the following in fleshing out "Sir Laurence's" mannerisms:

- Olivier's "Big 3" Shakespeare films - Henry V, Hamlet, Richard III

- Laurence Olivier: Confessions of an Actor - An Autobiography

- Lord Larry: The Secret Life of Laurence Olivier by Michael Munn

- Laurence Olivier - A Life, a Granada Television interview by Melvyn Bragg

- The Entertainer (1960 – film)

- The Prince and the Showgirl (1957 – film)

- Sleuth (1972 – film)

The films listed were particularly valuable for identifying physical mannerisms for Olivier, particularly at the age (53) he is depicted in this play. Of those films mentioned, I found Sleuth the most useful even thought it was filmed 10 years after the events in this play, so that should give you some idea of what my final performance looked like. And of course it didn't hurt that, like Ken Tynan, I have idolized Olivier since I was a youth and have seen most of his film and television work at some point or another. And I did see both the 2005 NYC Barrow Street Theatre and the 2007 Philadelphia Theatre Company productions of Orson's Shadow.

Notes on Pendleton’s Orson’s Shadow and Ionesco’s Rhinoceros

(above: George Hartpence as Laurence Olivier & Carol Thompson as Vivien Leigh)

Notes compiled by George Hartpence:

Orson's Shadow is a play that has a lot going for it. It's about the struggle to create art amid personal turmoil; it's about the conflict between different types of artists; it's even got some juicy gossip about legendary movie stars. And it's got some very witty and intelligent dialogue, courtesy of playwright Austin Pendleton.

It's 1960, and Orson Welles has been hired to direct Laurence Olivier in a London production of Eugene Ionesco's Rhinoceros. Welles has a lot to prove with this production: it's been nearly twenty years since he became a legend, thanks to Citizen Kane, but his demanding perfectionism has made him a pariah in Hollywood. Olivier, meanwhile, wants to prove that he's more than just the world's greatest classical actor; he wants to show that he can handle edgy, modern works like Ionesco's. He is also struggling to make a clean break from his tormented wife, Vivien Leigh, and create a new life with his lover (and Rhinoceros leading lady) Joan Plowright. Critic Kenneth Tynan is on hand, too, to assist Welles with the production.

Playing well-known, recognizable figures can be a tricky proposition; our actors in Orson's Shadow generally steer clear of direct imitation – relying instead on a few physical mannerisms or vocal inflections to convey a sense of the character’s famous persona.

If you’re unfamiliar with Hollywood history you need not be deterred from seeing Orson's Shadow, now being staged at the ActorsNET of Bucks County, as despite the play's mostly factual gathering of stage and screen legends backstage at the Royal Court Theatre in London, each of the impressive characters, director Orson Welles, thespian Laurence Olivier, stars Vivien Leigh and Joan Plowright, both of whom shared marriage vows with the former, and storied critic Kenneth Tynan, find plenty of time to run down their list of credits and accomplishments throughout the night.

And leave it to playwright Austin Pendleton to insert such egotistical rants throughout Orson's Shadow, occasionally while breaking the fourth wall, without ever being anything but acutely accurate in his characterizations of actors in general, who often find time to slip in a name drop or credit whenever the situation allows. Pendleton is a spot-on observer of human characters, and much of this play is built upon such intuitive examinations of theatrical legends.

While Ionesco's play, Rhinoceros, is a comment on totalitarianism and group conformity as a small French town, with the exception of one man, all turn into rhinos, there are strong thematic similarities between Ionesco's modern classic and Austin Pendleton's behind-the-scenes look at the staging of this play.

In Rhinoceros, Ionesco's characters literally transform into pachyderms, representing modern society's easy ability to turn into unfeeling and hardened creatures who have left their humanity behind. Similarly, Welles in real life and in the play is a large, hulking, domineering individual whose singular and determined sense of artistic vision often made him appear aggressive and bullying to others. Once he's put into a rehearsal room with Laurence Olivier, the stage is set for a showdown as the two men occasionally go at each other like wild beasts.

But Rhinoceros is also about taking a stand as best seen by the play's hero Berenger (played by Olivier) who goes from apathy to action. "I'm not capitulating!" Berenger screams in the final line of Rhinoceros. Welles frequently screamed similar sentiments at the Hollywood studios who wanted him to conform to their ideas of how a movie should be made and edited. Despite having achieved fame at a young age for Citizen Kane, Welles spent the remainder of his film career unsuccessfully trying to assert his right to complete control and final cut privileges over his work.

Where Welles and Olivier ultimately have it out, though, is over the question of modernity. In Pendleton's play, Welles wants to direct Rhinoceros in the modernist fashion in which Ionesco conceived it. Olivier, however, known principally for performing Shakespeare, approaches the play (and tries to undo Orson's directing) from a romantic perspective. Olivier's new flame Joan Plowright had already made a name for herself performing Ionesco and Pendleton clearly positions Plowright not only as Olivier's new love interest, but also as the embodiment of modern drama, while Vivien Leigh represents not only Olivier's broken marriage, but also an older style of acting.

Orson's Shadow, then, is not a "simple" look at stubborn rhinoceros-like theatrical egos, but a clash of multiple ideologies: modernity vs. tradition, innovation vs. status quo, and the individual vs. the collective. Pendleton's play reveals both the rhinoceros and the non-conformist in Welles and Olivier, a struggle that both of them would fight between each other and internally for much of their lives.

Orson' Shadow received its world premiere at the Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago in January 2000, and subsequently premiered in New York City at the Barrow Street Theatre in March of 2005. Rhinoceros was originally produced on January 25, 1960, at the Odéon in Paris under the direction of Jean-Louis Barrault. Its London premier was on April 28, 1960 at the Royal Court Theater, directed by Orson Welles and starring Laurence Olivier and Joan Plowright. Ken Tynan was not involved in this production, though he did go on to work with Olivier at the National Theatre.

When Real Actors Play Real Actors by Jean Schiffman for Backstage Magazine

(above from left: George Hartpence as Laurence Olivier, Vicki Czarnik as Joan Plowright, Dale Simon as Orson Welles, Paul Dake as Ken Tynan and Mark Reilly as Sean)

June 17, 2008

Orson's Shadow, a play by actor Austin Pendleton, opened at Chicago's Steppenwolf Theatre Company in 2000. But when it landed Off-Broadway after several productions in other venues around the country, the cast knew there would be audience members who idolized, and maybe even knew, the icons that appear as characters in the play: Vivien Leigh, Orson Welles, Laurence Olivier, Joan Plowright, and the critic Kenneth Tynan. New York University acting teacher Lee Roy Rogers, who originated the role of Leigh, says the actors never knew who might attend each performance -- the likes of Woody Allen, David Bowie, Ian McKellen. "People had amazing attachment and identification with Leigh," he says. "And there were people who knew her as well," including actor Eli Wallach, Dick Cavett, and Tynan's son Matthew. Pendleton had also met Leigh.

Providing Leigh-Way

Rogers says she has always been told of her resemblance to Leigh and that she loved Leigh in films. Still, she says, "it's always a concern when you play someone in the public eye that you'll not humiliate yourself" or do them a disservice. Like the other actors I talked to, Rogers read everything she could find about her character, including watching Leigh's films and looking at photos of her. She also studied the floating way Leigh moved, observing her posture and gestures, and thought about her own grandmother, who, like the bipolar Leigh, had electric shock treatments. She discovered how Leigh placed her voice, and she adopted Leigh's particular British accent.

Rogers' castmate Jeff Still was cast in the original production as Welles. As he looks nothing like Welles, he wore a fat suit and high-rise shoes. He also worked on Welles' vocal resonances, capturing the man's cadences and breathiness rather than trying to lower his voice to match Welles'. "Nobody ever asks you to imitate anyone exactly, but you have to honor it, do your best," Still says. Knowing what Welles looked and sounded like was a starting point; after that, "it sounds a little glib, but you take a swipe at the essence of the character," he says. "An imitation would be very limiting." In the end, it's about the character's needs at the time.

British-born Sarah Wellington, who created the role of Plowright, agrees: "You cannot fall into the trap of doing an impersonation. I don't look exactly like Joan, but you do want to honor certain physical aspects."

For Chicago actor John Judd, playing Olivier was not just daunting but downright preposterous -- "To portray the guy everybody thought was the greatest actor in the English-speaking world!" he exclaims.

More useful to him was a documentary, Laurence Olivier: A Life, that was made when Olivier was 75, 22 years older than his age in Orson's Shadow, which is set in 1960. Judd nevertheless watched the documentary many times, absorbing the essence of the man until he felt haunted by Olivier. He lost weight to play him, worked on nailing details of gesture and physicality, and, unfortunately, developed vocal problems from speaking in Olivier's higher register. Judd, like Olivier, also likes to work from the outside in. "It was a life-changing role," he says. "As an actor, I learned to take no half measures.... Now I throw myself at everything like it's life or death. I loved him. I hated being him at times. He'll never leave me."

Similarly, Sharon Lawrence misses Leigh, whom she played in a recent Pasadena Playhouse production of Orson's Shadow. For her preparation, Lawrence listened to recordings of the star at press conferences to hear how she pitched her voice. She studied her tempo, especially in The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, when Leigh was the age she is in Orson's Shadow. "It was important to make sure that her mania and her behavior came from her personality and wasn't just generic," says Lawrence. Wearing a wig and wardrobe were helpful; she also used some of the personal characteristics she saw in Leigh's most famous role, Scarlett O'Hara in Gone With the Wind.

I got an email from acting teacher Larry Biederman, who directed The Ladies of the Camellias at Theatre First. "When actors play actors," he wrote, "I see it as an opportunity to be self-loving, gentle, forgiving, and come to terms with the...traits we associate with actors, from the stories of diva fits to the old 'Oh, you're an actor, which restaurant?' jokes." He added: "Perhaps playing an actor is an actor's opportunity to accept that to actually be the instrument of your profession is a beautiful, unique, and ultimately selfless calling."