The Cleopatra Plays

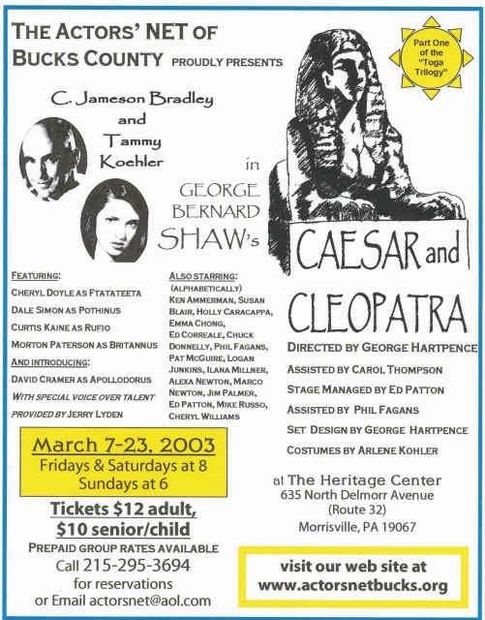

CAESAR AND CLEOPATRA

by George Bernard Shaw

directed by George Hartpence

March 7 through 23, 2003

ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA

by Wm Shakespeare

directed by Cheryl Doyle

April 25 through May 11, 2003

CAESAR AND CLEOPATRA

by George Bernard Shaw

directed by George Hartpence

March 7 through 23, 2003

C. Jameson Bradley as Julius Caesar and Tammy Koehler as Cleopatra

CRITICAL PRAISE:

Stuart Duncan writing for Princeton Packet publications said:

Actors' NET of Bucks County has mounted a stunning production of the Shaw play on its tiny stage at the Heritage Center in Morrisville. It will knock your eyes out with its majestic setting and costumes, then tease your brain into pretzels with the playwright's joyous leaps to surprising conclusions. In a series of impressive mountings, this one — with George Hartpence as director and a deliciously talented company of two dozen — may just be the most impressive ever.

The Great God RA & Sphinx gobos

Caesar and Cleopatra, a play written in 1898 by George Bernard Shaw, was first staged in 1901 and first published with Captain Brassbound's Conversion and The Devil's Disciple in his 1901 collection, Three Plays for Puritans. It was first performed at Newcastle-on-Tyne on March 15, 1899. The first London production was at the Savoy Theatre in 1907.

Caesar and Cleopatra marked George Hartpence's directorial debut with The Actors' NET of Bucks County. George also designed the set, which was subsequently used for the NET production of Wm Skakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra.

Jamie Bradley as Caesar and Tammy Koehler as Cleopatra

CAESAR AND CLEOPATRA Production Photos

Shaw's CAESAR AND CLEOPATRA cast

CRITICAL PRAISE

read the full review by Stuart Duncan in Princeton Packet

CaesarandCleopatra review 031203 (pdf)

DownloadDirector's Notes by George Hartpence

Caesar and Cleopatra - A Tale of Two Empires

I’d like to thank Joe and Cheryl Doyle for giving me the opportunity to make my directorial debut with such a wonderfully written and exciting play. An avid playgoer myself, I really enjoy reading the programme before and after the performance, in particular the director’s notes and any information on the history of the play or production background. I think these notes help make for a richer theater experience, but sadly one often has to travel as far as The Shaw Festival in Canada to find them. Below are a series of comments compiled from a variety of sources, most particularly the above referenced festival, which I hope will increase your appreciation of the many facets of this show.

Shaw was deliberately playing with history when he sat down to write Caesar and Cleopatra. Written in 1899, the play premiered in 1906, at a time when historical spectacle or "tableaux" were popular. Public education then was very classically based, and the history of the Roman conquests would have been much better known than it is to today's audience. Undoubtedly the first of Shaw’s really great plays, it is crammed with authentic historical detail, but plays fast and loose with the facts. It is clear that Shaw used the British Empire as a model for the Rome of Caesar's time. Caesar’s soldiers are made to talk like members of the British army that occupied Egypt in the 1880’s to protect Britain’s investment in the Suez Canal. Caesar’s secretary Britannus explains why all British men of social standing regard blue as the only respectable color to wear, in peace and war. Again and again in the course of the play Shaw throws some anachronistic joke at the audience, as if to say with a wink, “don’t believe a word of it!” Most dramatically, he presents the young Cleopatra, nearly twenty-one when she first met Caesar, as a girl of only sixteen.

Caesar and Cleopatra was also Shaw’s first attempt to put his idea of the Superman on the stage. Shaw’s notion of the Superman is of a kind of visitor from the future: a representative of the next stage of human evolution appearing on earth before his time. For an audience to feel his significance, he needed to appear in a society the audience could think of as primitive but also just like themselves; to strike contemporary listeners as one of us battling an ignorant past, but also as a superior being from a time yet unborn showing us how to become Supermen ourselves.

From his studies in the Egyptian gallery of the British Museum Shaw reasoned that human nature was many centuries older and more primitive than most supposed, and that it might go on evolving for centuries more, until what passed for civilization in nineteenth-century Europe might seem as barbarous as ancient Egypt. He felt the highest form of human intelligence is one that feels its unity with this immense river of time, at home at once with Socrates, Shakespeare and Darwin; capable of stretching back in imagination to the dawn of history and forward to a world fit for supermen and superwomen. That is the state of mind into which he maneuvers us.

At the heart of the play is a very human conundrum: How do you live a good life? Caesar is the most powerful man in the world – we see him on the edge of action, in private moments, in political meetings and beginning a military skirmish – and always we see this fascinating human being trying to accomplish the impossible: ethical government. His distraction, and indeed the counter-figure to whom he is attracted, is Cleopatra, who learns from him how to make herself obeyed but remains a creature of impulse.

Caesar and Cleopatra is a comedy about a tragedy, whose full meaning we grasp only if we carry Antony and Cleopatra in our heads. As such it is a perfect pairing with the next installment of our “Toga Trilogy.” Their heroines are the same unteachable woman. The visitor from the future comes to alter the course of history if he can, to try to avert Shakespeare’s tragedy. For a moment, when she rises to his vision of a kingdom of the future at the source of the Nile, Caesar hopes he can give Cleopatra the mind of a great ruler. But a moment later, she proves herself a woman who lives only in the present, addicted to such instant gratifications as cruelty and revenge. She sees no value in futures. When her bright day is done, she will choose the dark.

There is no Shavian resolution here, only a sense of loss and foreboding as these two extraordinary characters move toward their own inevitable ends.

Our intention is to make the themes of the play predominate over the spectacle, creating a world where the consequences of cultural conquest and warfare are real. We hope it will also remind the audience that the conflict in the Middle East is as old as history, and that Shaw's play can be read as a primer on how to rule in difficult times.

I hope you enjoy tonight’s production.

George Hartpence

Historical Notes:

Egypt was one of the most troublesome areas of the Roman Empire in the first century BC, especially when ruled by the famous Cleopatra (69 – 30BC). The daughter of Ptolemy XII, she was the last monarch of the Macedonian dynasty that ruled Egypt between the death of Alexander the Great in 323BC and its annexation by Rome in 31BC. Through Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra she became known as one of history’s great lovers, though most historians consider her political achievements more astonishing: the Greek biographer Plutarch commented, “Plato admits four sorts of flattery, but she had a thousand.” In history (though not in Shaw’s play), she became the lover of Julius Caesar when he came to Egypt in 48BC, bore a son by him, and lived for a time in Rome. After Caesar’s assassination she returned to Egypt, where she later became the lover and then wife of Caesar’s bigamous protégé Marcus Antonius (82 – 30BC). Besides Hannibal, Cleopatra was the only foreign ruler that Rome feared: Antony and Cleopatra’s defeat at Actium and their suicide the next year cleared the way for the Roman Empire of Julius Caesar’s nephew Octavian, who took the title Caesar Augustus.

Musical Note:

Most of this evening’s incidental music comes from two film scores composed by Sir Arthur Bliss – The Shape of Things to Come and Caesar and Cleopatra. A falling out between the composer and the director of the 1945 film Caesar and Cleopatra resulted in the rejection of Bliss’ proposed score in favor of another composer’s work. Tonight we hope to correct, at least in part, that injustice.

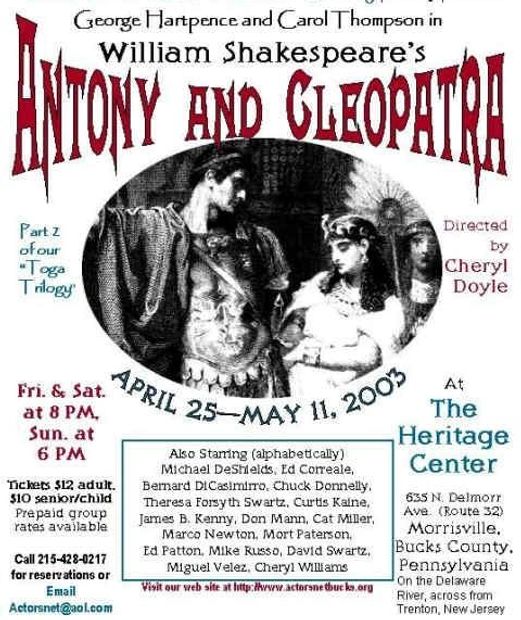

ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA

by Wm Shakesperae

directed by Cheryl Doyle

April 25 through May 11, 2003

Carol Thompson as Cleopatra and George Hartpence as Antony

CRITICAL PRAISE:

Stuart Duncan writes for Princeton Packet publications:

Actors' NET of Bucks County has developed a knack for taking huge projects, fashioning them to fit its postage-stamp space at the Heritage Center in Morrisville, Pa., snipping away excess material, doubling and sometimes tripling cameo roles and offering rewarding, comprehensive productions to its knowing audiences.

The latest triumph is Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra, seldom staged and unwieldy, but passionate and fiery.

…ultimately the production rests with George Hartpence and Carol Thompson as the title characters. We have seen the two paired before — principally in Camelot, Becket and My Fair Lady. Both have a superior sense of language and impeccable timing. More importantly for this particular production, however, they have a depth of passion that sets the tone of the evening from the first scene. Shakespeare's tale demands we believe that Antony, despite his mastery of war maneuvers and personal bravery, became so much putty when Cleopatra turned on her considerable charms. Hartpence and Thompson, engaged to be married on a June Sunday this summer, leave no doubt as to the passion of the relationship.

Carol Thompson as Cleopatra and George Hartpence as Antony

Antony and Cleopatra is a historical tragedy by William Shakespeare, originally printed in the First Folio of 1623.

The plot, based on Thomas North's translation of Plutarch's Life of Mark Antony, follows the relationship between Cleopatra and Mark Antony from the time of the Parthian War to Cleopatra's suicide. The major antagonist is Octavius Caesar, one of Antony's fellow triumvirs and the future first emperor of Rome.

The tragedy is a Roman play characterized by swift, panoramic shifts in geographical locations and in registers, alternating between sensual, imaginative Alexandria and the more pragmatic, austere Rome. Many consider the role of Cleopatra in this play one of the most complex female roles in Shakespeare's work. She is frequently vain and histrionic, provoking an audience almost to scorn; at the same time, shakespeare's efforts invest both her and Antony with tragic grandeur. These contradictory features have led to famously divided critical responses.

ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA Production Photos

design graphics for Antony and Cleopatra

Shakespeare's ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA cast

CRITICAL PRAISE

read the full review by Stuart Duncan of the Princeton Packet

AnthonyandCleopatra review 043003 (pdf)

DownloadPlot Synopsis - Antony and Cleopatra

Following the assassination of Julius Caesar and the battle of Philippi, Mark Antony, Octavius Caesar and Lepidus are the joint rulers of the known world.

Antony, however, is captivated by Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, and is neglecting his military responsibilities to spend time with her at her court in Alexandria, where they live a life of luxury and self-indulgence. This scandal is now the talk of Rome and has created a dangerous rift between Antony and young Octavius Caesar.

News comes from Rome that Fulvia, Antony's wife, is dead. More urgently, the power of the triumvirate is being challenged by Pompey, son of Julius Caesar's former rival, Pompey the great. Antony is forced to return to Rome and resume his responsibilities. When it is suggested that he should cement the alliance with Octavius by marrying his sister, Octavia, Antony agrees. His friend and comrade-in-arms Enobarbus, however, predicts that Antony will not be able to break with Cleopatra. Back in Egypt, the news of Antony's marriage sends Cleopatra into a jealous tirade.

On the brink of war, Antony and Octavius make peace with Pompey and celebrate the treaty with a feast. Shortly afterwards, however, Antony learns that not only has Octavius attacked Pompey after all, but he has also spoken scornfully of Antony in public and has had Lepidus imprisoned on dubious charges. Antony sends Octavia back to negotiate with her brother while he returns secretly to Alexandria.

News arrives in Rome that Antony and Cleopatra have crowned themselves and their children kings and queens in Alexandra. Antony's desertion of Octavia is the final straw. Octavius declares war on Egypt.

The Egyptian forces lose the sea-battle of Actium when Antony deserts the battle to follow Cleopatra's fleeing ship. Antony is consumed with shame and despair. However, hearing that Octavius has offered to make a secret treaty with Cleopatra, he rouses himself for a second, victorious battle.

On the eve of the third battle, Antony's soldiers are nervous and fear bad omens. Even the faithful Enobarbus deserts him for Octavius.

In the event, the Egyptian fleet surrenders and Antony, in his fury, accuses Cleopatra of betraying him to Octavius. She retreats from his anger to her monument and, hoping to bring him round, sends a false report that she is dead. On hearing this, however, Antony attempts suicide and is brought to Cleopatra's monument to die in her arms. Rather than be captured and enslaved by the Romans, Cleopatra also kills herself, using a poisonous snake brought to her concealed in a basket of figs.

With all his enemies eliminated, Octavius returns victorious to Rome.