CYRANO de BERGERAC by Edmond Rostand

George Hartpence as Cyrano de Bergerac

translated and adapted by Anthony Burgess

at The ActorsNET of Bucks County

April 4th through 20th, 2008

Produced by Marco Newton

Directed by Cheryl Doyle

Assitant-Director: George Hartpence

Stage manager: Jennifer Dzama

Set Design: George Hartpence

Lighting Design: Andrena Wishnie

Fight Choreography: Mark Holbrow

Critical Praise: "What a delight... a lovely evening of theater..." S. Duncan, Princeton Packet

‘Cyrano de Bergerac’

Actors' NET gets romantic with one of the most popular and celebrated of all French plays.

The Princeton Packet - TimeOff

Tuesday, April 8, 2008 11:57 AM EDT

By Stuart Duncan

The Actors’ NET revival is no small challenge — there is a cast of 21 covering the 43 roles in the drama. Leading the procession is the husband and wife team of George Hartpence and Carol Thompson and it is they who brilliantly plow through the extraordinary dialogue. And they do it with such panache that one is tempted to believe it is everyday talk, when in fact it is the height of poetic fancy. They have considerable help, of course, from Chuck Donnelly as Le Bret; from Constance Carey as Roxane’s Duenna; from Tom Orr as the rapacious Comte De Guiche; from Walter Smyth in multiple roles, but especially as a Capuchin monk.

What a delight to see the wonderful show once more and how rare to find a community group audacious enough to tame it. Cheryl Doyle has directed with great insight into its complexities, including some serious swordplay, complicated scene changes and large ensemble scenes. It remains a lovely evening of theater and be fairly warned: the show will certainly sell out, so make reservations and make them early.

Panache

puh-nash’, fr. French empenner (to feather an arrow), fr. Old Italian pennacchio; fr. Latin pinnaculum (small wing); also pin, pinnacle, and pennant

Panache is one of those glorious, elusive words that’s impossible to pin down with an exact translation, which is why we’ve retained its French form in English. In simplest terms, panache refers to the feathered plume of a military helmet. This is the meaning Cyrano invokes in Act IV when he speaks of King Henry IV, who urged his soldiers to rally behind his white plume, which will always be found “on the road to honor and glory.” But when Cyrano speaks this word again at the end of the play—his final word in fact—it has acquired metaphorical dimension, suggesting at once a commitment to valor, a certain flamboyant elegance, self-esteem verging on pride, and also a certain je ne sais quoi.

Rostand himself argued against limiting the word to a dictionary definition, as he explained in his Discours upon acceptance into the Académie Française in 1903: “What is panache? To be a hero is not enough. Panache is not greatness but something added to greatness and stirring above it. It is something fluttering, excessive—and a bit curled. If I was not afraid of being too pressed to work on the Dictionary myself, I would propose this definition: panache is the spirit of bravery. It is courage dominating the situation to the point of needing to find another word for it. […] To joke in the face of danger, that is the supreme politeness. A delicate refusal to take oneself tragically, panache is then the modesty of heroism, like the smile with which one apologizes for being sublime. […] A little frivolous perhaps, a bit theatrical certainly, panache is only a grace: but this grace that is so difficult to maintain in the face of death, this grace that assumes such force — this is the grace I wish for us.”

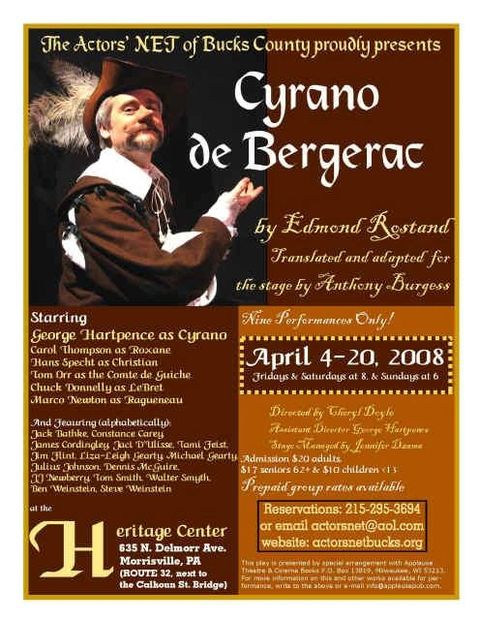

CYRANO de BERGERAC at the ActorsNET

ActorsNET poster

Edmond Rostand - playwright

Edmond Rostand was born April 1, 1868 into a bourgeois family in the southern port city of Marseille.

He was a brilliant student who, although he loved literature and the arts, studied law at his father’s urging. At the same time, however, he began writing poetry and drama. When Rostand arrived in Paris from his native Provence, he brought with him “the sunshine that flooded his childhood,” as one exuberant admirer has put it. He had no affinity for the somber slices of life that followers of naturalism were creating all around him.

His first play, Les Romanesques, was produced at the Comédie-Française in 1894. Based on Romeo and Juliet, it later became the basis for one of the longest-running musicals in Broadway history, The Fantasticks. The legendary Sarah Bernhardt starred in his next two plays, La Princesse lointaine (1894) and La Samarataine (1897) before Cyrano de Bergerac burst upon the world stage and turned its young author into an overnight sensation. His next play, L’Aiglon, appeared a few years later, followed by several more plays and patriotic poems. But Rostand’s health was deteriorating, and apparently he couldn’t even take a walk in Paris without being surrounded by adoring crowds. Desperate for privacy, he decided to move back to the South of France.

After several years of silence, Rostand brought forth his only other major work, Chanticler, in 1910. The morning after its opening in Paris, the daily newspaper in Butte, Montana, devoted not a column but its entire first page to that event—an indication of Rostand’s lingering fame. However, the work was pronounced a failure and Rostand retired to his luxurious villa at the foot of the Pyrenees. He threw himself into the French effort during World War I and died six weeks after the war ended in 1918, at the age of fifty.

Benoit Constantin Coquelin - originator of the role Cyrano de Bergerac

Opening Night - 28 December 1897 - 200 performances

Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac was performed for the first time December 28, 1897 at the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin in Paris. The character of Cyrano was played by Benoit Constant Coquelin, for whom the role had been written. The success of this piece was so astonishing that forever afterward Rostand feared slipping from that pinnacle of popularity in the eyes of the public.

Rostand (along with everyone else connected with the production) was initially convinced that the play was doomed to fail. His foreboding progressed to such an extent that just as the curtain was going up, Rostand fell to his knees at Coquelin’s feet and cried, “My poor friend, have ruined you.” His fear was quickly assuaged, however, for when Cyrano made his first entrance, he was saluted by “Bravos” that never stopped. Every line had the same effect, as applause greeted speech after speech. When the curtain fell at the end of Act I, nine curtain calls announced the triumph. After Act II, the ecstatic audience clamored, “Author! Author!”

The general enthusiasm was such that during the third act, George Clemenceau, the president of the Conseil (Cabinet) announced that he would be decorating M. Rostand that very evening with the Legion of Honor—France’s most prestigious award. At the conclusion of the performance, delirium reigned, with shouts of joy and thunderous applause lasting for two full hours. Men threw top hats into the air and women tossed fans and gloves onto the stage as the actors returned for more than 40 curtain calls. The next day, Paris was ablaze with excitement and the amiable 29 year-old author basked in the glory of becoming a national hero overnight. In 1901, Edmond Rostand became the youngest man ever admitted to the Academy, thereby securing forevermore his status as a master of French arts and letters.

French critics were effusive in their praise:

“Now, there is one more masterpiece in the world!”

“A great heroic-comedic poet has taken his place in contemporary dramatic literature, and that place is first.”

“All who create bow today before the triumphant young genius.”

“A great poet, from whom we can hope for absolutely everything, opens the 20th century in a dazzling and triumphant manner.”

Cyrano’s popularity can be at least partially attributed to the fact that the prevailing theatrical milieu featured naturalism, symbolism, well-made plays, some experimental fare, and light boulevard divertissements—all of which were vastly different from Rostand’s boldly romantic heroic comedy. A further explanation can be seen in the condition of French society at the end of the 19th century, which was still reeling in humiliation from its defeat in 1870 against Prussia. Many critics saw Cyrano as a play that reconnected France with the romantic tradition of cloak-and-dagger stories that had been buried since the days of Alexandre Dumas and Victor Hugo. Audiences identified with him, saluted him, admired him, and grieved for him.

Cyrano de Bergerac played in Paris for many years after its propitious opening, reaching its 1000th performance in 1913, and Coquelin reprised the title role hundreds of times until his death. The play was translated into dozens of languages, with Cyrano rapidly becoming a character known around the world.

Publicity Photos

preliminary poster design

Cast List

CYRANO Set Design by George Hartpence

Act I: A theatre in Paris -1640 - L'hôtel de Bourgogne

Cyrano de Bergerac Synopsis

Act I

In the theatre hall of the Hotel de Burgundy, awaiting the night’s play, Christian, a young but somewhat doltish soldier, anxiously looks for the beautiful Roxane to appear in her box. Christian is passionately in love with Roxane; however, he fears he will never have the courage to speak with her. Others in the audience are awaiting the arrival of Cyrano de Bergerac because the actor Montfleury, Cyrano’s enemy and one of Roxane’s suitors, is to star in the play, and Cyrano had threatened him with bodily injury if he appeared.

Finally Roxane arrives, the play begins, and Montfleury comes onto the stage. Suddenly a powerful voice orders him to leave, the noble Cyrano appears, and the performance is halted. Valvert, another of Roxane’s suitors, insults Cyrano, by pointing out his large nose, and Cyrano, sensitive about what he knows is a disfiguring feature, challenges Valvert to a duel. Cyrano, to show his contempt for his adversary, composes a poem while he is sparring, and with the last line draws blood.

Cyrano confesses to a friend that he is in love with his cousin—Roxane--despite the fact that he could never hope to win her because of his ugliness. At this point, Roxane’s chaperone interrupts to give Cyrano a note from Roxane, who wants to see him. Cyrano is overcome with joy.

Act II

The next morning, while waiting for Roxane, Cyrano composes a love letter to Roxane, which he leaves unsigned because he intends to deliver it in person. However, when Roxane appears, she confesses she loves Christian and asks Cyrano to protect him in battle. Cyrano sadly consents to do her bidding.

Christian joins the famed Gascony Guards, and he and Cyrano become friends. He confesses his love for Roxane and begs Cyrano’s help in winning her by composing tender, graceful messages. Although his heart is broken, Cyrano gallantly agrees and gives Christian the letter he had written earlier. This begins the deception wherein Cyrano writes beautiful letters and speeches, and Roxane falls in love with Christian’s borrowed eloquence.

Act III

Eventually, Christian decides he wants to speak for himself. Under Roxane’s balcony one evening, he tries, but must ask the aid of Cyrano, who is lurking in the shadows. Cyrano, hidden, tells Christian what to say, and Roxane is delighted over the sweet words she thinks are Christian’s. However, a monk interrupts bearing a letter from Comte de Guiche, who wants Roxane as his mistress and who is commander of the cadets. The letter says that he is sending the cadets into battle, but he is remaining behind for one night to see Roxane. Roxane pretends the letter directs the monk to marry her to Christian immediately, which he does. The marriage is not consummated, however, because the cadets leave for the front.

Act IV

During the following battle, Cyrano risks his life to carry letters to Roxane, and she never suspects the author of these messages is not Christian. Later, Roxane joins her husband on the battlefield and confesses that his letters had brought her to his side. Realizing that Roxane is really in love with the nobility and tenderness of Cyrano’s letters, Christian begs Cyrano to tell Roxane the truth. But Christian is killed in battle shortly afterward, and Cyrano swears never to reveal the secret.

Act V

Fifteen years pass; and Roxane, grieving for Christian, is retired to a convent, carrying his last letter next to her heart. Each week Cyrano visits Roxane, but one day he comes late, concealing under his hat a mortal wound inflicted by an enemy. Cyrano asks to read aloud Christian’s last letter; as he does so, Roxane realizes that it is too dark for Cyrano to see the words, that he knew the contents of the letter by heart, and that he must have written it; she also recognizes his voice as the one she had heard under her balcony on her wedding night. She also realizes that for fifteen years she has unknowingly loved the soul of Cyrano, not Christian. Roxane confesses her love for Cyrano, who dies knowing that, at last, she is aware of his love and that she shares it with him.

CYRANO de BERGERAC at ActorsNET - Act I

Ragueneau describes Cyrano's nose. Marco Newton (center) as Ragueneau, Walter Smyth (left) as First Marquis & JJ Newberry as Brissaille

CYRANO de BERGERAC at ActorsNET - Act II

The Ragueneau's examine the pastry lyre. Marco Newton (left) as Ragueneau & Tami Feist (right) as Lise Ragueneau

CYRANO de BERGERAC at ActorsNET - Act III

Cyrano (George Hartpence - left) and Roxane (Carol Thompson - right) share a secret.

CYRANO de BERGERAC at ActorsNET - Act IV

The starving cadets react to Bertrandou's flute playing.

CYRANO de BERGERAC at ActorsNET - Act V

Sisters of the Ladies of the Cross. from left: Jaci D'Ulisse, Tami Feist, Connie Carey

CYRANO cast party

The Real Cyrano de Bergerac

Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac

The character of Cyrano de Bergerac is not a fictional creation of Edmond Rostand. The real Cyrano was a famous swordsman and a provocative poet, philosopher, and social satirist in seventeenth-century France. Everything that happens in the play actually occurred in Cyrano’s life except what many now remember about the story–his unrequited love for Roxane. Although he often wrote love poems as was the fashion of the day, he did not dedicate them to anyone in particular.

In fact, sources close to the actual Cyrano, especially his life-long friend Henri Le Bret, characterize the man as shy and reserved around women. Rostand did borrow names from history for this romance however: Cyrano did have a cousin named Madeleine (Roxane’s real name) who married Christian, Baron de Neuvillette.

Born on March 6, 1619, Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac had the title “de Bergerac,” but no claim to the actual lands or revenue from them.

In spite of his limited means, he entered the swashbuckling Parisian world of plumed hats, lace-trimmed velvet doublets, and rapiers sticking out like a cock’s tail from under the cape slung over one shoulder with poise and self-confidence.

He joined Carbon de Castel-Jaloux’s company of the King’s Cadets, a company of Gascons in which he was welcomed because of his Gascon title even though he was not really from Gascony. During his time with the company, he became a formidable swordsman, known as “le démon de bravoure.”

His most famous adventure, narrated in Rostand’s play, was his single-handed battle against one hundred men at the Porte de Nesle in defense of his friend, the poet Lignière, whose verse had mocked the Comte de Guiche.

While Cyrano rarely initiated a challenge, he never refused a fight, often acting as a second in two or three duels a day. In fact, he joked in a letter to a friend, “It would be false to say I am the first among men, for in the last month I swear I have been second to everybody.”

But there was one subject that would rouse Cyrano to challenge another to a duel – his nose.

Contemporary engravings do show a large nose, especially in relation to his mouth which appears quite small, but not a nose of the gargantuan proportions that legend memorializes. Nevertheless, Cyrano was very sensitive about his nose and would not tolerate any allusions to its size.

In his major work, L’Autre Monde, a philosophical and satirical treatise that reads like science fiction, his utopian society honors men with large noses –the larger the nose, the greater the honor.

After the siege of Arras (portrayed in the play), Cyrano left Castel-Jaloux’s company and devoted himself to his writing under the patronage of Duc d’Arpajon from 1652.

Cyrano began to be associated with the Libertins, free thinkers who included Molière and the poet Lignière. At their rowdy meetings, they often castigated the Cardinal and the Jesuit priests in verse. Thus Cyrano got the reputation of being an atheist, even a blasphemer.

This notoriety caused the failure of his only play to be produced during his lifetime, La Mort d’Agrippine: the audience rioted and drove the actors from the stage when they misunderstood Cyrano’s use of the word l’hostie, hearing host (as in the Holy Sacrament) instead of hostage.

Cyrano’s only other play, Le Pedant Joué, based on one of the hated teachers of his youth, was not produced until after his death, but that did not stop Molière from stealing a passage containing the now famous line, “Que diable allait-il faire dans cette galère?” which appears in Moliere's Les Fourberies de Scapin.

Cyrano’s enmity toward the actor Montfleury, which opens Rostand’s play, is well-documented. He mocked the actor claiming he was unfit for the stage because of his enormous bulk and ordered him to retire or face a certain death. Montfleury took the threat seriously and did not perform for over a month, after which he was allowed to resume his career. Cyrano was not alone in his ridicule of Montfleury; he also appears as an object of laughter in one of Molière’s plays.

The final years of Cyrano’s life were spent composing L’Autre Monde which explored the possibility of space travel to utopian worlds on the moon and the sun where one could pay for a meal with a sonnet and where people chose their king and had the right of veto.

The character Cyrano details several of these methods of flight in the play as he distracts de Guiche while Roxane and Christian marry. In L’Autre Monde, he describes a box that he found on the moon that has an eerie resemblance to a phonograph 230 years before Edison’s innovation.

Cyrano made many enemies during his lifetime, and whether the block of wood that landed on his head as he entered his patron’s home was dropped on purpose or fell by accident will never be known. The blow caused a concussion from which he never recovered; he died on July 28, 1655, fourteen months after the accident, at the age of thirty-six.

Cyrano de Bergerac's close friend Le Bret never left his side during the illness and kept his promise to publish his works after his death.

Almost 250 years later, in 1897, Edmond Rostand revived the legend of Cyrano, but he transformed the disillusionments suffered by the real man into an actual romance filled with disappointment certainly, but also with an ideal passion and nobility–with panache.

The theatrical community lacked confidence in Rostand’s play: forcing the author to pay for the actor’s costumes himself. Even Rostand had serious doubts, and minutes before the curtain rose, he apologized to Constant Coquelin, who was to play the role of Cyrano, and asked his forgiveness for involving him in such a fiasco.

But the undying applause for play, that night and thereafter, changed its destiny forever. Adding to its fame are the many films, musicals, and stage adaptations that are regularly performed in many languages, all over the world.

Cyrano de Bergerac: Heroic Comedy or Romantic Tragedy

George Hartpence as Cyrano and Carol Thompson as Roxane

From Utah Shakespeare Festival Insights, 1992

In the heart of the naturalistic movement in France, Edmond Rostand returned to the romantic verse drama. In 1897, after Sarah Bernhardt had starred in several of his plays, Rostand reached his peak when Coquelin the elder (Benoit Constant Coquelin) took the title part in the poetic drama that won the most enthusiastic popular reception in dramatic history: Cyrano de Bergerac.

The play is based very loosely on the life of an actual French poet and soldier (1619-1655), a free-thinker and author of a few plays and of the satires The States and Empires of the Moon and The States and Empires of the Sun. In the play, Cyrano is a long-nosed daredevil who, thinking himself too ugly for Roxane, aids the inarticulate Christian to woo her. Cyrano writes Christian’s love letters, and, in a superb balcony scene, whispers from the dark the poetic phrases that gain Christian entrance to Roxane’s heart and to her chamber. Christian dies in the wars, however, and many years later Roxane in her convent discovers, as Cyrano is dying, that he was the author of the letters, that his was the spirit she had always loved. Roxane sighs: “I loved but once, yet twice I lose my love.” Cyrano’s sense of inferiority he bends to his glory; his love leads to his sacrifice. Yet the final moment of ecstasy atones for a barren lifetime.

In fact, “Cyrano de Bergerac” for purposes of classification may be called a romantic tragedy [although Rostand spoke of it as a heroic comedy]. The play, however, combines so many elements of the dramatic art that more explanation seems necessary. Act One is full of local color. It is a picture of early seventeenth century France. Life seems almost to be overflowing. There is a restless, noisy audience made up of mischievous pages, gay young spirits, charming ladies, soldiers, tradesmen, and even pickpockets. The action is a delightful mixture of nonsense, of swagger, of romance, of fantastic courage and wit. Act Two, in Rageneau’s pastry shop, adds a comic note and introduces the Gascons, every one a baron and a liar, and reveals the extent of Cyrano’s affection and his self-sacrificing devotion. Act Three idealizes the impossible love of the hero in the glorious balcony scene, and we have the brilliant ‘moon’ speeches which might be chanted, so lyrical is the poetry and so rhythmical the swing of the lines. Our souls are touched by the sincerity, the passion of Cyrano’s affection, the words, the gestures, the emotion of the perfect lover. Act Four presents the encampment of the Gascon Cadets just before battle, and charms us with its poetry depicting the bravery of empty stomachs, and then surprises us with the dramatic appearance of Roxane in her fantastic carriage. Finally, we have, in Act Five, the peace of a convent garden, and the quiet courage of the old swashbuckler, quick-witted, self-sacrificing, independent as ever, still hating shams and fearless even in the face of death” (Noble’s Comparative Classics [New York City: Noble and Noble, Publishers, lnc.], 43-44).

The story is presented in a style that recaptures both the swagger and the preciosity of the seventeenth century. Its verse mingles bombast and grandiloquence, flourish and gallantry with sadness and devotion. The lightness of the period is caught in pastry-cook Rageneau, patron of poets. Its recklessness gleams on the clashing swords, as Cyrano composes a ballade while fighting a duel. The play is a colorful and consummate tapestry of romance, beneath its carefree bravado playing a quiet undertone of sacrifice and sadness.

Carol Thompson as Roxane and George Hartpence as Cyrano

Cyrano de Bergerac: Optimistic Idealism

by James Mills

From Utah Shakespeare Festival Midsummer Magazine, 1992

The fin-de-siècle period in France was a time of continued disillusionment from the disastrous results of the Franco-Prussian war, of political and social division caused by the stormy Affaire Dreyfus, and of uncertainty from the inefficiency and instability of the Third Republic. It was a time of turbulence in literature when naturalism was passing from the scene and symbolism was running its course. But with Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac came a new impetus from neo-romantic idealism which took a struggling France into the more optimistic Belle Epoque of the early twentieth century.

After the play’s opening in 1897, Emile Faguet, the renowned literary critic, boldly declared that “A great poet decidedly appeared yesterday . . . on whom Europe is going to fix its eyes with envy, and France with a proud and hopeful delight” (Jules Haraszti, Edmond Rostand [Paris: Fontemoing et Cie, 1913], 123). (All quotations in this paper which were originally written in French have been translated into English by James Mills.) So pronounced was Rostand’s impact that it was said that “France suddenly became alive with the appearance of Cyrano” (Marc Andry, Edmond Rostand, le panache et la gloire [Paris: Plon, 1986], 78). Dubbed “the king of La Belle Epoque,” Rostand went on to dominate the French stage from 1897 until his death in 1918 (Andry, 11).

PRACTICALLY UNKNOWN. Prior to Cyrano de Bergerac, Rostand was practically unknown to the public. His play, Les Romanesques, was performed only fifty times in ten years, while La Princesse lointaine was a failure. Another play, La Samaritaine, which appeared in the same year as Cyrano, was performed only to a limited audience. Yet, other than Corneille’s Le Cid and Hugo’s Hernani, no French play has had such an immediate success as Cyrano.

As a playwright Rostand had an intimate knowledge of the theatre and “was a master craftsman, with a high degree of theatrical intelligence, with scenic sense, with a delight in solving technical difficulties” (Thomas Doyle and David Hoffman, Ed., Romeo and Juliet and Cyrano de Bergerac, trans. Howard T. Kingsbury [New York: Noble and Noble, Pub., Inc., 1963], 23). His literary masters included Shakespeare, who gave him the spirit of enchantment, Corneille, who taught him about lúesprit précieux, and Racine, who caused him to appreciate the tragic. His sense of the comic was influenced by Molière, his verve and wit by Regnaud, his use of vaudeville by Labiche, and his refinement of subtle sentiments by Marivaux. (For additional information on Rostand’s literary formation, see chapter 2 of Haraszti’s Edmond Rostand.)

The insertion of the author’s life into Cyrano has been much discussed by a number of his biographers. Alba della Fazia Amoia is one who has related the youth’s experience as a boarder at school writing love letters for a friend who then copied them to send to his girlfriend to “the immortal trio of Cyrano, Christian, and Roxane” (Edmond Rostand, Twayne Series [Boston: G. K. Hall, 1978], 63). Rostand’s wife, Rosemonde Gérard, herself a poet, included an anecdote in her book about her husband that sheds light on how the idea first came to him for Cyrano de Bergerac. While spending a summer in Luchon, he met a young man grievously disappointed in love, wrapped up in his sorrows. Later, Edmond met the young lady, who spoke passionately of the young man: “‘You know, my little Amédée, whom I had judged to be so mediocre, is marvelous; he’s a scholar, a thinker, a poet.’” (Amoia, 63). When Rostand realized that Amédée was, in reality, none of these but rather “a pale reflection of her ideal,” the idea for Cyrano was born.

HISTORICAL INACCURACIES. The historical basis for the play has also been much debated, for there was a real Cyrano who lived in the time of Louis XIII and, like the fictional character, had a large and ugly nose. However, a number of critics have pointed out the historical inaccuracies between the fictional Cyrano and the real one, none of which, however, diminishes the poetic value of the play. Martin Jacob Premsela, for example, has written that the real Cyrano was a noble, although of obscure origin, who may have been born in the domaine of Bergerac or Bergerat in the surroundings of Paris. He reminds the reader of the claim that Cyrano may have even been of Italian origin (Edmond Rostand [Amsterdam: J. M. Meulenhoff, 1933], 75, note 4). He points out that Roxane’s real name was Magdeleine Robineau, and not Robin, and that Cyrano and Montefleury remained friends, not enemies. Furthermore, he states that Cyrano did, in fact, take a protector, the Duke of Arpajon (78).

Amoia has suggested that the real Cyrano was born in Les Halles district of central Paris on 6 March 1619, and that the “de Bergerac” title appeared later when the father acquired two castles in the outskirts of Paris, one of which was known as Bergerac. As the second child, Savinien de Cyrano was authorized to use the title of the second castle to become Cyrano de Bergerac (64).

According to Amoia, the real Madeleine Robineau was married in 1635 to the Baron de Neuvillette and loved to dance and to eat and was noted for her “peach complexion” (65). She took charge of Cyrano’s social education until he enlisted as a cadet with the Noble Guards of the Gascon captain, Carbon de Casteljaloux. After being wounded in battle at Mouzon in 1639, Cyrano left the cadets to join the regiment of the Counts and participated in the siege of Arras where he and his comrades would spend the long hours smoking and playing cards.

One of the soldiers, a newlywed named the Count of Canvoye, would receive as many as three letters a day from his young bride, but it was Cyrano who supplied the rather dull husband with love poems to send back to her. Stabbed in the throat by an enemy saber, Cyrano recovered consciousness to learn that Madeleine’s husband had been killed in battle. When he returned to Paris to convalesce, he further learned that Madeleine was spending her life in prayer and penitence. However, upon seeing her in the convent he hardly recognized her for her clothes were “of the poorest sort,” and her former “peach complexion” was hidden under long grey hair. It is reported that “he fled from the convent, horrified, and vowed never to return (Amoia (65-66).

While at the residence of the Duke of Arpajon, Cyrano was struck on the head by a falling beam causing him to spend one year on the brink of death. His friend Henry le Bret assisted him, and Madeleine is said to have visited him twice. A short time after her second visit, on 28 July 1655, Cyrano died.

“THIS DISASTROUS ADVENTURE.” The play named after him was performed on 28 December 1897 at the Théâtre de la Porte-Saint-Martin with Constant Coquelin, to whom the work was dedicated, in the role of Cyrano. Initially, nobody had given the play much hope for it was a long work in five acts, expensive, with over fifty speaking parts and five décors, with complicated stage directions, and written about an anachronistic subject. In a moment of discouragement, Rostand apologized to Coquelin, saying: “Pardon! Ah! Pardon me, my friend, for having led you into this disastrous adventure” (Emile Ripert, Edmond Rostand, sa vie et son oeuvre [Paris: Hachette, 1968], 75-76).

Happily, for as long as one hour after the closing curtain, most of the audience remained in the theatre giving an enthusiastic standing ovation. A new French hero was born.

“TO SHOW, TO PREACH, TO EXALT.” The primary goal of Cyrano de Bergerac is “to show, to preach, to exalt the dignity of love” (Premsela, 68). That is the basis of the panache, rather than pride, misanthropy, or social, moral, intellectual independence. The dignity of Cyrano lies in his selflessness, while for Christian it is in his ultimate abandonment of a love that he has not earned (Premsela, 68).

It is a heroic comedy that approaches Corneillean tragedy by glorifying the efforts of energy (Haraszti, 235). It is a comedy where tragedy is much present and where death intrudes: Cyrano is killed by an enemy, Christian commits a form of suicide by throwing himself into the fore of the battle to die, and Roxane symbolically dies as she casts aside love and society for voluntary confinement in a convent (Premsela, 68).

Rostand was successful in recreating the life and atmosphere of an age, that of Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu and the early years of Louis XIV and Cardinal Mazarin. It was a time of national achievement, the Golden Age of French power and culture when French was the universal language of diplomacy and of polite society, and French taste and art were internationally adopted and imitated. He captured the social life of the Age of Splendor with “movement, exuberant spirit, romance, affectation, intrigue, self-sacrifice all crowded together as they were in those hectic years” (Doyle, 29). Ultimately, Rostand appealed to the collective soul of modern France seeking to find itself again.

Louis Haugmard’s claim at the end of World War I that “Cyrano de Bergerac . . . has remained the greatest theatrical success of all time,” (6) typifies the esteem in which the play was held at the time of Rostand’s death in 1918 (Edmond Rostand [Paris: E. Sansot et Cie., 1918], 6). Upon returning to his former school, the collège Stanislas, the playwright summarized the universal appeal of Cyrano de Bergerac with the following admonition to the students: “Be yourselves young Cyranos! Have panache, have soul” (Andry, 79)! Even Cyrano’s fictional rival, the Count de Guiche, recognized the hero’s greatness when he acknowledged: “He lives his life / His own life, his own way—thought, word, and deed / Free!” (Edmond Rostand, Cyrano de Bergerac, trans. Brian Hooker [New York: Bantam Books, 1981], 178. Ultimately, Cyrano’s integrity remains intact and his panache untarnished.

Carol Thompson as Roxane, George Hartpence as Cyrano, Chuck Donnelly as LeBret & Marco Newton as Ragueneau

Cyrano de Bergerac: A Romantic Melodrama

By Jerry L. Crawford

From Utah Shakespeare Festival Souvenir Program, 1992

Labeled in various ways, Cyrano de Bergerac has been called “heroic comedy” (by its author, no less), “romantic comedy,” and “tragicomedy,” among others. Yet, perhaps it is best to refer to it as a “romantic melodrama.” That it is romantic is indisputable. Also, theatre at its most truly theatrical is melodrama—elevated, intensified reality stretching into a world of fancy, improbability, and imagination. The play also personifies a lyric expression and exotic grandeur. It is a magic carpet to a world in which everyone delights in escaping. At its opening, 28 December 1897, Cyrano de Bergerac caused a furor of excitement not seen since 1830 when Victor Hugo’s romantic Hernani stirred major controversy. Yet, Rostand and his epic play did not stir up controversy; rather, audiences uniformly cheered Cyrano as a man who embodied the very essence of French nationalism, along with his own individualism. Rostand relied on a plot of unrequited love and the language of romantic lyricism to guide his audiences through one adventure after another, culminating in a classic scene in which idealism triumphs and the supremacy of love is assured forever. Yet, while Cyrano was universally popular and was translated at once into many languages, an unusual fact must be kept in mind: the play was in many ways anachronistic, existing out of its given time.

Cyrano de Bergerac was presented to the world in an age conditioned to realism and naturalism. Regardless, there was no dissenting voice to its success. The popularity of this play has never dimmed. Why? Perhaps because there is always a place in our imaginations and hearts for romance, poetry, moonlight, and dashing behavior. Further, the genius of Rostand rested in his ability to balance intellect and emotion, unite poetry and reality, and weld idealism with rationalism without destroying a synthesized theatre experience. His key device in reconciling these seeming opposites was to employ a serious form, but to offset it through self-criticism and laughter on the part of the central figure. Rostand’s finest characters always have a sense of humor. Cyrano, for instance, possesses far more than his great nose; he possesses the unusual capacity to recognize what is immutable in the human experience and simultaneously smile.

Regardless, Cyrano’s outlook is not superficial because all his reactions are thoroughly intellectualized—they may be launched from his heart, but they reach us from his marvellous mind. The content and structure of the play are much the same.

Detractors have long accused Rostand of imitating Hugo, of distorting facts (indeed, Cyrano is a kind of history play), of exaggerating emotions, of indulging in verbal pyrotechnics, and of being too personal and limited in style and scope. In other words, they accuse Rostand of being a romantic. His supporters, on the other hand, applaud his verbal virtuosity, lyrical dialogue, elevating idealism, wit, grace, gentle satire, and ability to manage feats of enviable theatricality. In other words, they champion him for being a romantic. That he is somewhat limited in comparison to, say, a Shakespeare (an inevitable comparison in Cedar City, Utah) must be conceded; yet, Rostand has not been excelled in the particular dramatic style that made him famous.

It may be that Edmond Rostand was a minor poet with one major work; yet, despite his failures and shortcomings, Rostand will live on because he has given to the theatre its first, quality romantic melodrama. Rostand has also given to a tedious, often drab world “the gesture of a Cyrano.” Cyrano de Bergerac: an anachronism that is always in vogue, always in line with our hearts. With tears in our eyes, but a smile on our lips, we bow to Cyrano’s grand “white plume.”

Paris - circa 1640

The play Cyrano de Bergerac begins in the hall of the Hôtel de Bourgogne where a disparate crowd awaits the opening of a new play. People from all social strata are gathered—valets, royal guards, pickpockets, students, artisans and food vendors. Standing in the parterre or pit, they eat, drink, play cards, flirt and pick fights. Two galleries of loges are reserved strictly for aristocratic patrons such as the Comte de Guiche and the Vicomte de Valvert, who enter ceremoniously and make their way to the upper level, while noblemen of the highest rank are permitted to sit on the stage.

The Hôtel de Bourgogne was the first theatre in Paris, built in 1548. The King’s Players, his first permanent company of actors, was installed in 1610 and reigned supreme for many years. The royal troupe featured legendary performers such as Bellerose and Montfleury—masters of the bombastic acting style so popular with audiences.

L’esprit précieux du XVIIème siècle.

There appeared in France during the 17th Century a social and philosophical movement called préciosité which established a code of polite behavior among aristocratic ladies and gentlemen. After many years of bloody civil war, les précieuses sought to eliminate the vulgar language and crude behavior that had become commonplace, replacing them with elegance, refinement and graciousness. Although eventually deemed to be artificial and snobbish, préciosité was celebrated by artists and poets, influencing the fashions, speech and literature of the day. Women, who no longer wished to be considered mere objects used by men, set about redrawing the laws of a society that considered marriage no more than a financial arrangement. All cultured gentlemen were required to understand and practice gallantry, and everyone was preoccupied with discussions of idealized romantic love.

The Aristocracy.

The first member of the House of Bourbon to achieve royal rank was Henry IV, formerly Henry of Navarre, who ruled from 1589-1610. He was succeeded by his son, Louis XIII, who became king at the tender age of 11 and reigned under his mother’s regency until 1617, when he rebelled and had her imprisoned. Louis XIII appointed Cardinal Richelieu as Chief Minister in 1624, and together they reconcentrated power in the French throne. Members of noble class existed within a strict hierarchy based largely upon land holdings. Titles, which were either hereditary or bestowed by the King, were (in descending order) duc, marquis, comte, vicomte and baron. Chevalier (knight) was a rank within the titled nobility and seigneur (lord) was not a title, but referred only to the possessor of a certain kind of property. Louis XIII’s successor was his eldest son, Louis XIV, whose legendary reign as the Sun King from 1643-1715 marked the apogee of royal absolutism throughout Europe.

The Siege of Arras.

In 1640, the Flemish city of Arras, along with most of the ancient French province of Artois, was under Spanish rule. As the Thirty Years War entered its final phase, Louis XIII sent an army into Flanders, where they settled in for a long battle outside the city walls of Arras.

The outlook was bleak for the Spanish until massive reinforcements arrived, trapping their besiegers and cutting off supply lines. The starving French troops tried to appease their hunger on minnows fished from the River Scarpe and on sparrows—the only game available.

Ultimately, the great Condé succeeded in breaking through to Doullens to get supplies and recaptured Arras for France. But the French soldiers who remained to fight met with a devastating assault by the Spanish. Bearing the brunt of this attack was the regiment of Gascon cadets led by Captain Carbon de Castel-Jaloux, including the Baron de Neuvillette, who was killed in the battle, and Cyrano de Bergerac, who suffered a massive throat wound from which he never fully recovered.