The Merchant of Venice by Wm Shakespeare

What's new on the Rialto?

The Merchant of Venice was written sometime between 1596 and 1598. Although classified as a comedy in the First Folio, and while it shares certain aspects with Shakespeare's other romantic comedies, the play is perhaps more remembered for its dramatic scenes (particularly the trial scene), and is best known for the character of Shylock.

The title character is the merchant Antonio, not the more famous villain, the Jewish moneylender Shylock, who is the play's most prominent figure. Although Shylock is a tormented character, he is also a tormentor, so whether he is to be viewed with disdain or sympathy is up to the audience (as influenced by the interpretation of the play's director and lead actors). As a result, The Merchant of Venice is often classified as one of Shakespeare's problem plays.

The Merchant of Venice holds a special place in my list of plays simply because it was the very first play I auditioned for after high school... a good deal after high school. It is also the play (or more particularily the audition) when I met my dear good friend, Dale Simon. He and I happened to meet on the street outside and walked in together to the audition at the Artist Showcase Theatre in Trenton, New Jersey. In fact, I met many people during this first production who would become dear friends over the course of my association with Shakespeare`70: Frank and Gail Erath, Steve Kazakoff and Carol Kehoe, Tom Moffit, Tom Curbishley and Cheryl Leaver, David Geisler, Lee Harrod and Howard Goldstein.

1990

1990

1990

June 1990 Shakespeare`70 production

at the

Washington Crossing Open Air Theater

directed by Frank Erath

George Hartpence as Solanio

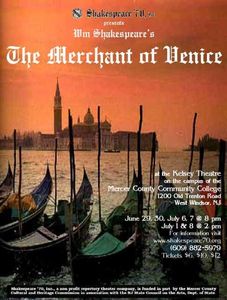

2007

1990

1990

June 29 - July 8, 2007

Shakespeare`70 production

at the Kelsey Theater

on the campus of

Mercer County Community College

directed by Frank Erath

George Hartpence as Antonio

2013

1990

2013

May 31 - June 16, 2013

ActorsNET of Bucks County production

at The Heritage Center, Morrisville, PA

directed by Cheryl Doyle

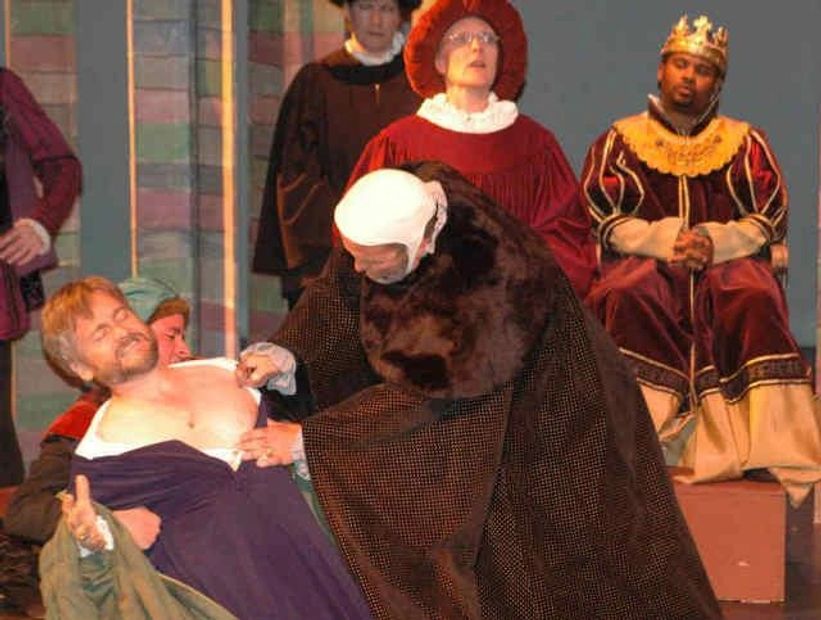

George Hartpence a Shylock

Cast Lists - The Merchant of Venice

The Merchant of Venice (2013) at the ActorsNET

George Hartpence as Shylock

The ActorsNET of Bucks County production

May 31 - June 16, 2013

at

The Heritage Center

635 Delmorr Avenue

Morrisville, PA

Directed by Cheryl Doyle

Stage Managed by Kathleen Landes

Set Design by George Hartpence

Lighting Design by Andrena Wishnie

Costumes by Cheryl Doyle

Critical Praise

Anthony Stoeckert writes for the Central Jersey Princeton Packet TimeOff entertainment section:

SHYLOCK is probably Shakespeare’s most troublesome, and troubling character, but George Hartpence has risen to the challenge of playing the Jewish moneylender in the striking production of The Merchant of Venice being presented by Actors’ NET of Bucks County in Morrisville, Pa., through June 13.

In Mr. Hartpence’s hands, Shylock is smart, funny, vengeful, greedy and heartbreakingly human.

With Cheryl Doyle directing, the courtroom scene is one of the best in the play, though it’s troubling. Shylock’s evilness is on full display as he demands that pound of flesh — even doubling his money doesn’t satisfy him. … Shylock is wrong to demand his pound of flesh (though the law must take some of the blame for recognizing this bond), but after Shylock is cleverly defeated, he is forced to give up his heritage and become a Christian. This results in the play’s most powerful moment, and a brilliant breakdown by Mr. Hartpence. But at the same time, the scene made me squirm, because the play’s heroes, led by Antonio, pile insults and hurts on Shylock to the point where I felt like I was watching a schoolyard bullying.

Critical Praise

Gina Vitolo-Stevens writes for Stage Magazine:

The most jarring moment of the play is the animalistic cry from Hartpence when his Shylock must surrender all that gives him life. Portia has him remove his yarmulke and he crumples to the floor. It’s one of the most moving few seconds to uncomfortably sit through. It’s his surrender of soul that each person in the audience can palpably feel when you hear his muffled cry.

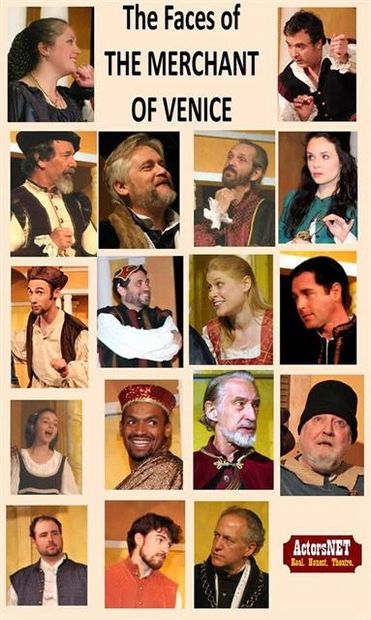

Cast Roster - The Merchant of Venice (2013)

George Hartpence (right) as Shylock & Rob Norman (left) as Tubal

DeLarme Landes (left) as Antonio & Brian Jason Kelly (right) as Bassanio

Kyla Mostello-Donnelly (left) as Portia & Maryalice Rubins-Topoleski (right) as Nerissa

Mark Swift (left) as Launcelot Gobbo & Marco Newton (right) as Old Gobbo

Aaron Wexler (center) as Gratanio

Amanda Hecht as Jessica & John Helmke as Lorenzo

"The Salad Boys"

Eric Wishnie (left) as Solanio & Michael Wurzel (right) as Salerio

James Cordingley as the Prince of Aragon

Carol Campbell as the Prince of Morocco

Mort Paterson as the Doge

ON STAGE by Anthony Stoeckert

Springing Into the Bard

Actors' NET explores “The Merchant of Venice”

Preview article appearing in The Princeton Packet

Shylock can be a troubling character for modem sensibilities. He personifies the stereotype of the greedy Jew, and he's the target of endless anti-Semitic insults hurled by the play's protagonists, especially Antonio. Perhaps most troubling of all, the play ends on a supposed happy note (or what would be in Elizabethan times) as Shylock is “redeemed" by agreeing to convert to Christianity, thus saving his soul, in exchange for some of his fortune. But Shylock is also a victim, and voices one of Shakespeare's most famous, and eloquent speeches, in which he demands to be treated as person (“If you prick us do we not bleed ... ")

The goal for Actors' NET, which is staging Merchant of Venice May 31-June 16 at the Heritage Center in Morrisville Pa., is to delve into the text to do justice to Shakespeare, and to Shylock, who IS a villain, but often a sympathetic one.

"You can't cut out the fact that Antonio behaves or has behaved, terribly badly to Shylock," says Cheryl Doyle, who's directing Merchant of Venice (and who runs Actor's NET with her husband Joe). "That's part of what has to be worked into his character, just as how Shylock responds has to be worked into it. And we have to have, in the long run, some overriding point of view, but not to the point of changing the play."

Complicated as he is for today's theatergoers, Shylock remains a great character, one that actors want to play.

"For everyone who does Shakespeare, there's a bunch of roles on the bucket list and Shylock is certainly one of them," says George Hartpence, who plays Shylock and stars in Actors' NET Shakespeare presentations. "He's one of the most fascinating characters that Shakespeare has written, but it's also one of most problematic plays there is to modern audiences."

He adds that the key to producing Shakespeare for an audience is reading, and re-reading, the text. "There are so many things you can find within his character and the things that are said by him and about him, that can give you justification for a sympathetic interpretation, but there's one thing you can't forget: Shylock is a would-be murderer," Mr. Hartpence says. "And that's extremely important in this particular play. So you need to be able to accommodate both of those things."

"I'm so happy to get a chance to do 'Merchant,' " Mr. Hartpence says. ”Because I think when you look deeply at Merchant, the play IS about human values, and how being human sometimes gets in the way of human values. Shakespeare does what Shakespeare does beautifully, he takes a mirror and holds it up to nature and says here's what people are really like, and here’s what people could be like."

George Hartpenec a Shylock and Kyla Mostello-Donnelly as Portia

George Hartpence as Shylock and DeLarme Landes as Antonio

Merchant of Venice (2013) Performance Photos

George Hartpence (left) as Shylock Rob Norman as Tubal

Merchant of Venice (2013) Rehearsal Photos

"In sooth, I know not why I am so sad." DeLarme Landes (left) as Antonio & Brian Jason Kelly (right) as Bassanio

SYNOPSIS: The Merchant of Venice by Wm Shakespeare

In Venice, young Bassanio needs a loan of 3,000 ducats so that he can properly woo a wealthy heiress of Venice named Portia. To get the necessary funds, Bassanio entreats his friend Antonio, a merchant. Antonio's money, unfortunately, is invested in merchant ships that are presently at sea; however, to help Bassanio, Antonio arranges for a short-term loan of the money from Shylock, a Jewish usurer. Shylock has a deep-seated hatred for Antonio because of the insulting treatment that Antonio has shown him in the past. When pressed, Shylock strikes a terrible bargain: the 3,000 ducats must be repaid in three months, or Shylock will exact a pound of flesh from Antonio. The merchant agrees to this, confident in the return of his ships before the appointed date of repayment.

At this stage of the play, Portia is introduced: due to her father's will, all suitors must choose from among three coffers—one of which contains a portrait of her. If a man chooses the right one, he may marry Portia; however, if he chooses wrong, he must vow never to marry or even court another woman. Princes of Morocco and Arragon fail this test and are turned away. As Bassanio prepares to travel to Belmont for the test, his friend Lorenzo elopes with Jessica, Shylock's daughter (who escapes with a fair amount of Shylock's wealth in the process). Bassanio chooses the lead casket, which is the correct one, and happily agrees to marry Portia that very night.

In contrast to this happiness, Antonio finds himself in a pinch. Two of his ships have already wrecked in transit, and Antonio's creditors—including the vengeance-minded Shylock—are grumbling about repayment. Word comes to Bassanio about Antonio's predicament, and he hastens back to Venice, leaving Portia behind. Portia, however, travels after him with her maid, Nerissa; they disguise themselves as a lawyer and clerk, respectively. When Bassanio arrives, the loan is in default and Shylock is demanding his pound of flesh. Even when Bassanio (backed now by Portia's inheritance) offers many times the amount in repayment, Shylock is intent on revenge. The duke, who sits in judgment, will not intervene. Portia enters in her guise as a lawyer to defend Antonio. Through a technicality, Portia declares that Shylock may have his pound of flesh so long as he draws no blood (since there was no mention of this in the original agreement). And, since it is obvious that to draw a pound of flesh would take Antonio's life, Shylock has conspired to murder a Venetian citizen; he has forfeited his wealth as well as his loan. Half is to go to the city, and half is to go to Antonio.

In the end, Antonio gives back his half of the penalty on the condition that Shylock bequeath it to his disinherited daughter, Jessica. Shylock also must convert to Christianity. A broken and defeated Shylock accepts in a piteously moving scene. As the play ends, news arrives that Antonio's remaining ships are returned to port; with the exception of the humiliated Shylock, all will share in a happy ending.

The Merchant of Venice (2007) for Shakespeare`70

George Hartpence as Antonio

June 29 - July 8, 2007

directed by Frank Erath

Shakespeare`70 production

at the Kelsey Theater

on the campus of Mercer County Community College

set design by Dale Simon

Critical Praise

Carol Kehoe as Portia, George Hartpence (right) as Antonio & Tom Curbishley (left) as Bassanio

Stuart Duncan, critic for The Princeton Packet says this is "a show that should be seen by everyone with even a minimum interest in Shakespeare. Beautifully set and costumed."

"And this production is the troupe at its very best — a blend of veteran actors much accomplished and used to working together to maximum effect. Among those veterans are the husband and wife team of Carol Kehoe and Stephen Kazakoff. Director Erath uses them to perfection in the top roles. Kehoe mixes a sensational comedy skill with her special brand of female diffidence and in her opening scene sets the mood of the evening as she taunts her pompous suitors when they try to pass "the test of the caskets," choosing between gold, silver and lead for her hand in marriage.

Scholars have always argued that the plot line was available only in Italian and therefore the simple Man of Stratford who did not read Italian could not have been the author of this 1595 play. But that's another discussion. While Ms. Kehoe taunts such actors as John Anastasio as The Prince of Morocco and Dale Simon as the Prince of Aragon, Kazakoff plays Shylock, the money lender, to perfection. Never once does he overact the dangerous dialogue, nor yet is he trapped by Shakespeare's devious plot twists. He is able to develop a very rare sympathy for the Jew and it adds a new dimension to the evening.

George Hartpence plays Antonio with his usual understated intelligence (it's actually the title role) and Tom Curbishley plays Bassanio, the successful suitor, with easy charm. Tracy Hawkins has a terrific time as Nerissa, Portia's maid and confidante. And Tom Moffit makes a return to the group after a three-year battle with a serious illness that has left him sightless, in the role of Old Gobbo. And what a welcome return it is."

Merchant of Venice (2007) Production Photos

The Merchant of Venice, Antonio. George Hartpence "In sooth, I know not why I am so sad."

The Merchant of Venice (1990) for Shakespeare`70

George Hartpence as Solanio

June 1990

Shakespeare`70 production

Washington Crossing Open Air Theatre

To this day, Dale Simon and I would be hard pressed to name off the top of out heads which of the two Tweedle-Dee and Tweedle-Dum characters, Salerio and Solanio, we actually played. It was great fun, though, and the beginning of a decades long obsession.

Merchant of Venice (1990) Production Photos

Steve Kazakoff (right) as Shylock, Dale Simon & George Hartpence (center) as Salerio & Solanio. David Harris (Leonardo - left) looks on

OVERVIEW: The Merchant of Venice

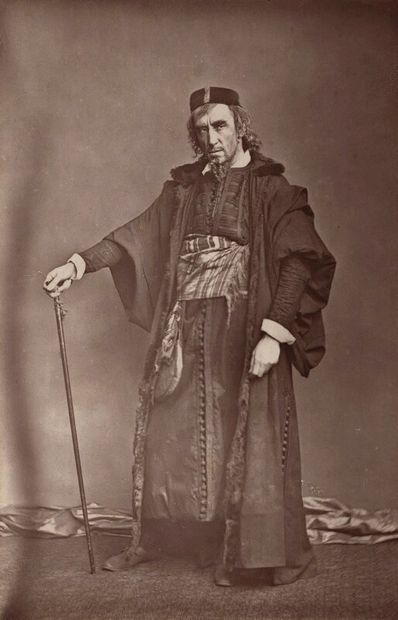

Sir Henry Irving as Shylock

Written sometime between 1596 and 1598, The Merchant of Venice is classified as both an early Shakespearean comedy (more specifically, as a "Christian comedy") and as one of the Bard's problem plays; it is a work in which good triumphs over evil, but serious themes are examined and some issues remain unresolved.

In Merchant, Shakespeare wove together two ancient folk tales, one involving a vengeful, greedy creditor trying to exact a pound of flesh, the other involving a marriage suitor's choice among three chests and thereby winning his (or her) mate. Shakespeare's treatment of the first standard plot scheme centers around the villain of Merchant, the Jewish moneylender Shylock, who seeks a literal pound of flesh from his Christian opposite, the generous, faithful Antonio. Shakespeare's version of the chest-choosing device revolves around the play's Christian heroine Portia, who steers her lover Bassanio toward the correct humble casket and then successfully defends his bosom friend Antonio from Shylock's horrid legal suit.

There are many possible texts that Shakespeare could have used in constructing The Merchant of Venice, and while we can confirm that he relied upon two particular sources, the others sources I will mention were likely, though not definitely, influences on Shakespeare. His chief source was a tale in an Italian collection entitled Il Pecorone or The Simpleton, written in 1378 by Giovanni Fiorentino, and published in 1565. No known English translation existed for Shakespeare to use, but it is possible, although very unlikely, that someone Shakespeare knew had translated his own private copy and gave it to Shakespeare to read. It is more likely that Shakespeare was more learned than people like to assume, and that he read the text in its original Italian. The story in Il Pecorone tells of a wealthy woman at Belmont who marries an upstanding young gentleman. Her husband needs money and has friend, desperate to help, goes to a money-lender to borrow the required cash for his friend. The money-lender, who is also a Jew in Il Pecorone demands a pound of flesh as payment if the money is not paid back. When the money is not paid in time, the Jew goes to court to ensure he receives what he is owed. The friend's life is saved when the wealthy wife speaks in court of true justice and convinces the judge to refuse the Jew his pound of flesh. Shakespeare adds the casket story line and the Shylock's usury -- in Il Pecorone the Jew lends the friend money without interest.

Portia's suitors and the game of casket choosing they must play for her hand in marriage are from the Gesta Romanorum, a medieval collection of stories translated by Richard Robinson, and published in 1577. Here is the excerpt from Gesta Romanorum relevant to The Merchant of Venice, as reprinted in the edition of Shakespeare's play edited by H. H. Furness:

Then was the emperour right glad of her safety and comming, and had great compassion on her, saying: Ah faire lady, for the love of my sonne thou hast suffered much woe, nevertheless if thou be worthie to be his wife, soone shall I prove. And when he had said thus, he commanded to bring forth three vessels, the first was made of pure gold, beset with precious stones without, and within full of dead mens bones, and thereupon was ingraven this posey: Whoso chooseth me shall finde that he deserveth. The second vessel was made of fine silver, filled with earth and wormes, and the superscription was thus: Whoso chooseth me shall finde what his nature desireth. The third vessel was mad of lead, full within of precious stones, and the superscription, Whoso chooseth me shall finde what God hath disposed to him.

Additionally, in approximately 1591, Christopher Marlowe wrote The Jew of Malta. Marlowe, considered by most to be the greatest playwright other than Shakespeare in the English language, crafted his hero, Barabas, the wealthiest Jew in Malta, no doubt from the same sources as Shakespeare used. Barabas is cunning and extremely intelligent, but his intellect prompts his downfall, and he dies in the trap that he set for his enemy. Marlowe's play was a wild success, and its popularity may have been the reason why Shakespeare decided to write his own version of the tale told in Il Pecorone.

The Merchant of Venice is significant as the first play Shakespeare wrote as a Dramatist first and poet second. The pre-Venice plays are notable for their long florid speeches, in which Shakespeare allows himself to wax poetical on every subject, drawing out very beautiful words and phrases. In Venice and the plays that followed, he had become a more restrained writer. He continued to indulge in his penchant for long speeches, but now those speeches were strictly in service of the plot. The most famous aspect of the play is the character of Shylock, and his famous speech. It is interesting to note that at the time Shylock was thought of as more of a villain than he is today: "When the play was first acted, there was little sympathy for him, and some surprise that he was let off so lightly." Modern analysts have questioned how Shakespeare actually felt towards Jews. Sadly, the play offers no definitive answers.

In the modern, post-Holocaust readings of Merchant, the problem of anti-Semitism in the play has loomed large. A close reading of the text must acknowledge that Shylock is a stereotypical caricature of a cruel, money-obsessed medieval Jew, but it also suggests that Shakespeare's intentions in Merchant were not primarily anti-Semitic. Indeed, the dominant thematic complex in The Merchant of Venice is much more universal than specific religious or racial hatred; it spins around the polarity between the surface attractiveness of gold and the Christian qualities of mercy and compassion that lie beneath the flesh.

Anti-Semitism in England

Prejudice against Jews increased in England around 1190 after non-Jews borrowed heavily from Jewish moneylenders, becoming deeply indebted to them. In York, about 150 Jews committed suicide to avoid being captured by an angry mob. King Richard I (reign: 1189-1199) put a stop to Jewish persecution, but it returned in the following century during King Edward I's reign from 1272 to 1307. The government required Jews to wear strips of yellow cloth as identification, taxed them heavily, and forbade them to mingle with Christians. Finally, in 1290 Edward banished them from England. Only a few Jews remained behind, either because they had converted to Christianity or because they enjoyed special protection for the services they provided. In Shakespeare's time 300 years later, anti-Semitism remained in force and almost no Jews lived in England. In fact, it is very likely that the only opportunity for Shakespeare to actually have seen a Jew with his own eyes was if he happened to witness the execution in 1594 on charges of treason of the unfortunate physician to Queen Elizabeth, Rodrigo Lopez. The Portugese Jew, professing Christianity, fell afoul of the Earl of Essex, who accused him of trying to poison the Queen. Christopher Marlowe, a contemporary of Shakespeare, wrote a play entitled The Jew of Malta, which depicted a Jew named Barabas as a savage murderer. Shakespeare, while depicting the Jewish moneylender Shylock according to denigrating stereotypes, infuses Shylock with humanity and arouses sympathy for the plight of the Jews.