The Tragedy of OTHELLO - The Moor of Venice

by Wm Shakespeare

produced by The ActorsNET of Bucks County

June 10th thru 26th, 2011

directed by Cheryl Doyle

staged by George Hartpence

featuring

Carlo Campbell as Othello

and

George Hartpence as Iago

with

Tess Ammerman as Desdemona,

Carol Thompson as Emilia

and

Brian Jason Kelly as Michael Cassio

Dramatis Personae

additional cast members

additional cast members

additional cast members

Allison DeKorte as Bianca, Cassio's lover

Mort Paterson as Brabantio, a Venetian senator, Gratiano's brother, and Desdemona's father

Aaron Wexler as Roderigo, a dissolute Venetian, in love with Desdemona

Jack Bathke as Duke of Venice, or the "Doge" and Lodovico, Brabantio's kinsman and Desdemona's cousin

Matthew Cassidy as Gratiano, Brabantio's brother

DeLarme Landes as Montano, Othello's Venetian predecessor in the government of Cyprus

Tom Harrelson, Erik Benrud, Daniel Reiher as Officers, Gentlemen, Messenger, Herald, Sailor, Attendants, Musicians, etc

Technical Credits

additional cast members

additional cast members

Stage Manager - Matthew Cassidy

Set Design - George Hartpence

Stage Combat Choreography - Steve Kazakoff

Dramaturg - Jack Bathke

Verse Coach - Mort Paterson

Lighting Design - Andrena Wishnie

Costume Design - Cheryl Doyle

Sound Design - Cheryl Doyle

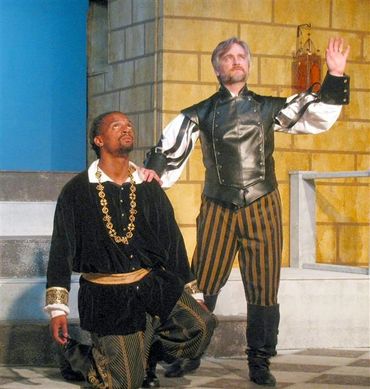

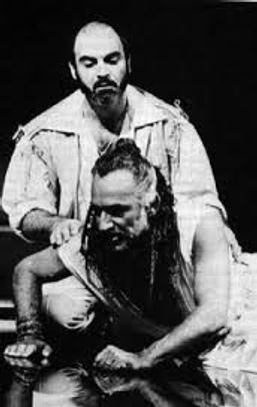

George Hartpence as Iago and Carlo Campbell as Othello

Critical Praise for OTHELLO at ActorsNET

'Othello'

Actors’ NET takes on one of Shakespeare’s great tragedies

Date Posted: Tuesday, June 14, 2011 6:33 PM EDT

by Anthony Stoeckert

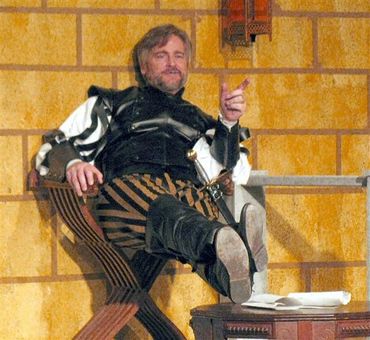

LET’S get right to the point, Actors’ NET of Bucks County’s staging of Othello is a major achievement, remarkable for a community group in fact. Give a lot of the credit to the actors, most of whom speak their lines with confidence and who actually act their roles rather than getting caught up Shakespeare’s language.

Despite its title, Iago is the play’s main character, at least in terms of driving the plot. Most of the story follows the villain’s scheme to convince Othello that Desdemona is having an affair with Cassio, leading to Othello’s destruction and Iago taking Cassio’s job.

George Hartpence is one of the area’s best community actors and his Iago doesn’t disappoint. Hartpence speaks his lines with such clarity and ease, as if he were having a conversation in a coffee shop — that is if a power-hungry warrior devised a plan to destroy everyone around him in a coffee shop.

Hartpence doesn’t resort to mustache-twirling villainy, he’s convincingly charming when dealing with Cassio, falsely loyal to Othello and intimidating and firm with his wife Emilia. Hartpence is so good I actually found myself buying Iago’s act, thinking he seemed like a decent sort. Hartpence does get his fun and powerful villainous moments during soliloquies, where his hatred for Othello and the world pour out of him.

Carol Thompson is Hartpence’s equal as Emilia, the wife of Iago (and Hartpence’s real-life wife). She’s also comfortable with the language and convincingly goes from dutiful wife to someone who realizes the awful truth of her husband.

Mort Paterson gives one of the night’s best performances as Brabantio, conveying the power of an influential man, the concern of a father and the anger of betrayal. Too bad the character isn’t in the play beyond the first act because I could have watched Paterson all night.

Files coming soon.

Othello - Act I - Venice

At Senior Brabantio's house

Othello - Act II - Cyprus

Carol Thompson as Emilia

Othello - Act III - Cyprus

Othello - Act IV - Cyprus

Pouring poison in Othello's ear: George Hartpence (left) as Iago & Carlo Campbell (right) as Othello

Othello - Act V - Cyprus

Planned ambush: Aaron Wexler (left) as Roderigo & George Hartpence (right) as Iago

Ian McKellen on Iago

Ian McKellen as Iago & Willard White as Othello in 1990

When in 1989 the Royal Shakespeare Company's ex-artistic director Trevor Nunn suggested a production of Othello as the last production at the old tin hut called "The Other Place" in Stratford-upon-Avon, the management hesitated, even though the renowned opera baritone Willard White was to make his dramatic debut as the Moor. It was rumoured that Nunn paid for the stage production and eventually for part of the costs to make a video version. Playing Iago would be a return to my partnership with Nunn at the same address where we had done Macbeth 13 years before. With scarcely 100 seats, it was an appropriate theatre for a play which is invariably domestic and where claustrophobia can contribute to the effect.

Iago is an easy part to bring off and rarely fails to impress. I am not the first to realise that there is no need to act the underlying falsity of the man, but rather to play "honest Iago" on all occasions. "Do not smile or sneer or glower — try to impress even the audience with your sincerity": Edwin Booth. As Iago confides the truth to the audience (as always in Shakespeare), they are privy to his deceit and the gulling of Roderigo, Cassio, Desdemona and Othello himself. It is an unfair advantage and early on Willard accused me of trying to get the audience on my side against him. I explained that I didn't need to try — Shakespeare had organised it that the villain's part should be the audience's portal into the action. The history of the play records many more serious misunderstandings between the Moor and his Ancient.

Within his confessional asides, Iago makes his motives clear. I wouldn't have known how to play the critical cliché of the man as the embodiment of all evil. So I played the jealous husband who suspects "the lustful Moor hath leaped into my seat" and can urge his boss to "beware of jealousy" because he himself is a victim of it. This plus what he takes to be Cassio's unfair promotion over him, is more than enough for him to hate. Mischief turns to mayhem as he warms to his successful attack on the commanding officer and his wife. It is yet another Shakespeare tale of what happens when soldiers are not fighting — they get up to no good. So Iago can be compared with Don John, Macbeth, Richard 3 — all admirable professional fighters who also go off the rails away from the battlefield. The costumes were updated to mid-19th century and the whole show was another example of Trevor Nunn's invariable basic approach to the classics — a belief that a naturalistic analysis of the characters will bring them explosively to life. It had worked with our Macbeth and The Alchemist and with Othello did so again. — Ian McKellen, May 2003

David Suchet on Iago's Motivations

David Suchet as Iago and Ben Kingsley as Othello in 1985

The extreme malevolence with which Iago plots the complete destruction of everybody around him is unparalleled by other villains and thus, much debate exists as to why the ensign is as vicious as he is. David Suchet, who played Iago at Stratford-upon-Avon in 1985, explores the motivations behind the role extensively and comments that no one has ever come up with a completely satisfying explanation for Iago's behavior. Instead we get a series of labels:

1.A smiling villain.

2.The latent homosexual.

3.The devils emissasary.

4.The playwright (i.e. creator of events and observer, who conducts the outcome).

5.The melodramatic machiavel.

Each of these poses a legitimate argument. The mock marriage of Othello and Iago provide evidence that the latter possesses a homosexual attraction to his general. The numerous comparisons, both direct and indirect, of Iago to a demon suggest that, at least in the minds of the characters, he may be doing a supernatural's bidding. He certainly spins a complex web and exercises a degree of control that rivals Shakespeare's own on Othello itself. Iago is also fantastically pragmatic, gaining great wealth from Roderigo and eventually a promotion from Othello; perhaps he was a student of The Prince. Or indeed perhaps, meager textual evidence aside, he is simple psychopathic, acting upon irrational and sadistic impulses while still managing to exercise reason.

Additionally, it is sometimes thought that Iago simply hates women, therefore, he want the most powerful women in his world, Desdemona who as the "general's wife is now the general" (II.iii.292) to be destroyed. This is most obvious when, after arriving on Cyprus, Iago banters with and then verbally attacks Desdemona and Emilia calling them "pictures out of doors, / Bells in your parlours, wild cats in your kitchens, / Saints in your injuries, devils being offended, / Players in your housewifery, and housewives in your beds" (II.i.113-116). He thinks of women as simple and lazy creatures accusing that they "rise to play and go to bed to work" (II.i.118). After all, Desdemona is essentially taking from Iago the man whom he may love, "Othello's marrying means that their friendship will never be the same again". However, since much of Iago's hatred seems directed towards Othello, too much faith cannot be placed on this explanation.

It is also possible that Iago acts, much like Othello eventually does, out of jealousy. Immediately, the ensign is envious of Cassio's promotion, feeling the other less deserving and greatly desiring the accolade for himself. Iago is not willing to accept living in Cassio's shadow but realizes that "He hath a daily beauty in his life / That makes me ugly" (V.i.18-19). In addition, he suspects that both Cassio and Othello might have made a cuckold of him, that is, either may have slept with Emilia. Although his suspicion of Cassio might simply arise from the fact that Iago himself is painting Cassio as an adulterer, he is more serious about Othello secretly charging that "I do suspect the lusty Moor / Hath leapt into my seat, the thought whereof / Doth, like a poisonous mineral, gnaws my inwards, / And nothing can or shall content my soul / Till I am evened with him, wife for wife" (II.i.282-286). If, however, Iago does indeed act out of jealousy we must be careful not to analyze him to closely. After all, "jealous souls will not be answered so; / They are not ever jealous for the cause, / But jealous for they're jealous" (III.iv.154-156), or as Suchet adequately translates "don't look for reasons in the behavior of jealous people".

There is not any ample supply of text to adequately confirm Iago's motivations as lying in one area or another. It is of course possible that his actions originate from a mixed background, but the general refusal to accept the test as ultimate on the part of academics and the subsequent searches for answers outside the play suggests otherwise. He is indeed a complicated character, one who at times, such as in his dealings with Roderigo, acts out of predominant self-interest, an understandable and natural human motive. However, at other times, the great lengths he goes to console Desdemona only to eventually plot her murder, appear to be the result of a serious psychosis. The text cannot always be trusted either as David Suchet points out: "Human beings are given to finding justifications for deeds or actions to make those deeds allowable in their own minds even though they are not always valid justifications. And so it is with Iago". Perhaps Iago is simply satisfied to do what he does so well, that is to "play the villain" (II.iii.310).

Honest, Honest Iago

"What's he then that says I play the villain?" — Iago, 2.3

Many critics, including Harold Bloom, have commented that although Othello is the title character, it is Iago's play. He rules the action and even the mindset of the other characters almost as if he were co-authoring the piece. His kindred in the canon are Richard III and the bastard Edmund, two other manipulative villains, but Iago reigns supreme in that category as the mastermind of destructive disinformation. He extracts money and valuables from Roderigo as if the Venetian were Iago's bank account. He sets up Cassio's drunken brawl as if his compatriots were chess pieces. He makes a beautiful young woman seem a whore in her newlywed and devoted husband's eyes. He's devastatingly perceptive about others, gifted at suggestion and innuendo, improvisationally brilliant, and uncannily lucky. In the ranks of villains, he's good—that is, bad.

Iago and Soliloquy

Like Richard Gloucester and Edmund, Iago has a special relationship with the audience, established early on and developed through the action of the play. Richard opens his play and establishes both himself and his audacious plots, enlisting the audience's complicity. Like Richard, Iago is his own color commentator.

Iago plunges into action for two scenes and then, near the end of the third, turns to the audience with almost a showman's wink, "Thus do I ever make my fool my purse." It's the equivalent of "Pretty slick, huh?" From that moment, in case we had any doubt, we know that we too are toys in the hand of a malignant entity. He explains his machinations, a fiendish psychic chemist toying with synapses and verbal poison—"To get his place and to plume up my will in double knavery. How? How? Let's see." His creative imagination is swift in response, recognizing the raw material and its potential, "Cassio's a proper man" and Othello is "of a free and open nature" (1.3.365, 374-6, 381). Pour these ideas together and the beaker of his brain starts to foam and smoke.

What Makes Iago Destroy? Why Now?

Each soliloquy is a prize, a piece of Iago's own psychic puzzle. We watch what he does; that is clear and horrifying enough. But why does he do it?—that is the question. Critics, directors, and actors have wrangled with Iago's psyche for centuries. We have motives aplenty; what is the trigger that makes him lethal now?

The first scene opens with the motive of thwarted ambition, potent enough in its own right to launch a retributive attack. Iago, who has fought side by side loyally with Othello, is passed over for the big promotion when the opportunity arises. Othello prefers Cassio, not an infantry officer but perhaps a strategist or artillery officer, the man Othello trusted as go-between in wooing Desdemona. This seeming betrayal ignites Iago's gasoline-soaked psyche. He bursts into hate-filled diatribe and immediately seeks to spoil, if not the wedding itself, certainly its aftermath. No calm wedding night for these newlyweds; not only Iago but also the Turkish fleet manage to interrupt it.

The second soliloquy offers more, and more disturbing, motives. Iago suspects Othello and also Cassio of sleeping with his wife, and his own jealousy "gnaw[s] his innards." The suspicion is false, but Iago does not care; he seeks to "diet his revenge," to infect Othello with the same disorder that plagues him, to "put the Moor / At least into a jealousy so strong / That judgment cannot cure," even, Iago says, "to madness." Does it take a madman to clone a madman? Or is it simple "knavery"?

For some critics, no amount of explanation adequately accounts for Iago's actions. In Coleridge's phrase, the ensign is "motiveless malignity." To act without reason or provocation, to destroy because one can, would put Iago in the camp of serial killers and other psychopathic sorts who are amorally immoral.

Sorting through the various motives and tracing them from Iago's core into his plotting is necessary, a kind of psychological C.S.I. We have an abundance of testimony, much of it in his own words, and we watch his behavior. Now is he stable or unstable, justified or perverse, suddenly pushed over the edge or long a schemer? Interpreting Iago is indeed one of the great rewards of studying the play.