The Tragedy of KING RICHARD III

by Wm Shakespeare

directed by Cheryl Doyle

ActorsNET of Bucks County production

presented March 5 through 21, 2004

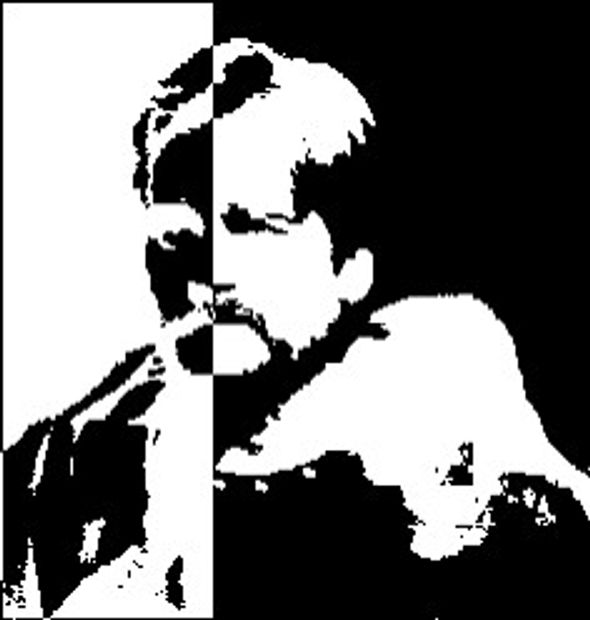

George Hartpence as Richard, Duke of Gloucester, later King Richard III

featuring:

Carol Thompson as Lady Anne

Dale Simon as Buckingham

C. Jameson Bradley as Hastings

David Swartz as King Edward IV

Aaron Wexler as George, Duke of Clarence

Susan Fowler as Queen Elizabeth

Steve Lobis as Lord Stanley

Stuart Duncan writes of George Hartpence's performance in the Princeton Packet:

"... a delicious performance from one of the area's most versatile actors. "

ActorsNET Production

Part One: Richard of Gloucester

Prologue: London. The Tower and Palace

Act 1, Scene 1: London. The Palace.

Act 1, Scene 2: Street in London.

Act 1, Scene 3: The Palace.

Act 1, Scene 4: London. The Tower.

Act 2, Scene 1: London. The palace.

Act 2, Scene 2: The palace.

Act 2, Scene 3: London. The palace.

Act 3, Scene 1: London. The City Gate.

Act 3, Scene 2: Before Lord Hastings' house.

Act 3, Scene 3: Pomfret Castle.

Act 3, Scene 4: The Tower of London.

Act 3, Scene 5: Beneath the Tower-walls.

Act 3, Scene 6: Baynard's Castle.

Act 4, Scene 1: Before the Tower.

Scene Break-down

Part Two: King Richard III

Act 4, Scene 2: London. The palace.

Act 4, Scene 3: The Tower.

Act 4, Scene 4: Before the palace.

Act 4, Scene 5: Lord Stanley’s house.

Act 5, Scene 1: Salisbury. An open place.

Act 5, Scene 2: The camp near Tamworth.

Act 5, Scene 3: Bosworth Field.

Act 5, Scene 4: Another part of the field.

Act 5, Scene 5: Another part of the field.

Condensed Plot Summary:

George Hartpence as King Richard III

Richard III

by William Shakespeare

After a long civil war, England enjoys a period of peace under King Edward IV. But Edward's younger brother, Richard, resents Edward's power and the happiness of those around him. Richard decides to ascend to the throne himself-and to kill anyone he has to in order to do it.

Richard begins his campaign for the throne by manipulating Lady Anne into marrying him and having his own older brother Clarence executed. After his sick older brother King Edward dies, Richard becomes Lord Protector of England - the person who will be in charge until the older of Edward's two sons grows up.

Richard's continuing reign of terror causes the common people of England to fear and loathe him, and alienates nearly all the noblemen of the court - even the power-hungry Buckingham. When rumors begin to circulate about a challenger to the throne named Richmond who is gathering forces in France, noblemen defect in droves to join his forces.

Richmond finally invades England. The night before the battle that will decide everything, Richard has a terrible dream: all the ghosts of the people he has murdered appear and curse him, telling him that he will die the next day. In the battle on the following morning, Richard is killed, and Richmond is crowned King Henry VII. Promising a new era of peace for England, the new King is betrothed to young Elizabeth in order to unite the warring houses of Lancaster and York.

George Hartpence as Richard of Gloucester

George Hartpence sa King Richard III

Critical Praise

Anita Donovan writes for the Bucks County Courier Times:

“George Hartpence brings the right touch of evil to the role.”

“Director Cheryl Doyle sets a fast moving pace and injects a humorous tone – even if it is gallows humor – whenever possible, making the increasing horrors more shocking. Hartpence makes Richard repulsive to the moral intellect while keeping him plausible as a human being – not an easy task.”

Stuart Duncan writes on March 10, 2004 for the Princeton Packet TimeOff entertainment section:

George Hartpence plays Richard (for the first act he is Richard of Gloucester, and by Act IV, Scene II, he is King). He begins by establishing clearly both that he is "misshapen" and that he is "determined to prove a villain," and does so with relish. In an inspired bit of text juggling, a monologue that closes Henry VI, Part III is used here to introduce our evening's journey. And then we watch, almost in awe, as Richard grins at evil, soothes anguish and banters with assassins. It is a delicious performance from one of the area's most versatile actors.

"On Playing Richard" by George Hartpence

Richard causes the untimely demise of his brother, Edward IV, by bringing news that the royal cellars have been depleted of Bombay Sapphire.

Wm Shakespeare's Richard III is my favorite character from the canon. I have wanted to play Richard as long as I have wanted to act. The opening monologue is the first Shakespearean speech I ever committed to memory. So when director Cheryl Doyle asked me what my "dream role" was, the answer to her question was simple and rapidly forthcoming. It was, therefore, a great personal triumph to portray him in this ActorsNET production.

Director Doyle and I worked for many months editing the script of Richard III into a more manageable form and length. As a result we were able to condence 3 hours of stage time from a 4 hour script (a link to the edited text is provided below) and to eliminate much of the character confusion so prominent in Shakespeare's histories - especially true where so many of the characters share the same first names: four Richards, three Edwards, two Henrys, two Georges, two Elizabeths. And nearly every one of them with the same surname: Plantagenet!

The result, I believe, was an eminently accessible version of what many consider to be a difficult play for modern audiences to appreciate, converting it from a historical pageant to a fast-paced thriller.

If you wish to understand Shakespeare as an actor, then look at Richard of Gloucester. He always speaks the truth - when he's talking to the audience, that is. I know of no other Shakespearean character who so completely and consciously takes the audience into his confidence. He seduces the audience so completely that you become his accomplice, and while you may not admire him, you certainly cannot help but enjoy him. He relishes his villany and feels completly justified in his actions. Unlike so many soloquies in other plays, it is not difficult for an actor to tell when Richard breaks the fourth wall and engages the audience directly and when Richard is speaking his own thoughts to himself.

Richard knows what he is and shares it with you - both his self-love and self-loathing. He embodies so much of what is faulity in the human condition, that he cannot truly be called an "inhuman" monster. Inhumane, yes. Inhuman, no. To borrow from another of the Bard's famous villians, his "black and deep desires" propel this play with juggernaut force to its inevitable end. For Richard the ends do justify the means - a Machiavellian sentiment present in all of us, yet under control (for the most part) in most of us.

In addition to working with Cheryl Doyle in editing the text, I was also given the opportunity to design the set for our production. With technical assistance from my friend and co-star in this production, Dale Simon, we designed a simple, Tudor-esque apearance while leaving plenty of open space and levels to accommodate the large cast. And Stephen Kazakoff worked out some amazing fight choreography for us that allowed my Richard to fight with axe and broadsword and for the "white boar" to get his comeuppance, appropriately enough, via a boar spear.

Richard of Gloucester - Part 1

Richard contemplates the crown of dead King Henry VI, before bringing it to the coronation of his brother Edward IV. Richard (George Hartpence)

Set Design by George Hartpence

RIII Boar Sigil

Adaptation of the White Boar emblem in Richard III's crest

front view

note use of Boar Sigil on wall right

White York and Red Lancaster Roses used throughout - emblems of the War of the Roses

second story platform center and "tower" on stage right

Richard the King - Part 2

Richard alone in the throne room with Catesby Catesby - right (Philip Katz) King Richard III - left (George Hartpence)

Cast List for RICHARD III at ActorsNET

Script - Richard III by Wm Shakespeare

Edited script of Richard III - 3 hour run time

Stage History & Historical Background

STAGE HISTORY

In the early 1590's, William Shakespeare wrote “The Tragedy of King Richard the Third,” his first blockbuster hit. Chroniclers Edward Hall, Raphael Holinshed, and Sir Thomas More, Shakespeare's presumed sources, deliberately distorted their accounts of Richard so as to augment public empathy and support for the reigning Tudor monarchs. Shakespeare, blending fact, fiction, and rumor, molded his Richard III into an exciting political figure. The play has had a long popularity beginning with the first actor to perform the role for Shakespeare, Richard Burbage, and the role has been a favorite among actors up to the present day.

In America, “Richard III” from the eighteenth century onward has been one of the most popular of Shakespeare’s plays. A host of Richards hissed their way into the consciousness of early American theaters and improvised playhouses from New York to the most distant outposts of the new country. “Richard III” was a favorite play on the showboats on the Mississippi and in the repertory companies that played in barns and halls on the frontier long before the railroads got there. In 1767, a performance of “Richard III” was chosen as the means of entertaining a delegation of Cherokee Indian chiefs on a diplomatic mission on New York. A New York newspaper reported that the Indians regarded the play with “seriousness and attention,” and perhaps with some wonderment at this revelation of the white man’s bloodthirsty iniquity.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Richard's reputation, through reasons of politics and envy, has been distorted through the ages. Most historians agree that Richard was cultured and intelligent, with a proven ability to govern. They concur that his deformity has been greatly exaggerated, and describe him as attractive but frail. The incidents in Shakespeare's play are based on historical fact; however, there is considerable debate as to whether Richard was indeed responsible for the murder of the princes in the tower, or the death of Lady Anne.

Shakespeare's audience knew the story of Richard III. The Wars of the Roses (1453-1497) between the Yorkists, whose badge was the white rose, and the Lancasters, traditionally identified by the red rose, resulted in some the most brutal battles in English history.

This split in the royal family occurred in the fourteenth century with the sons of King Edward III, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, and Edmund Langley, Duke of York. Marriages and intermarriages arranged among their descendants erupted in war as relatives killed and imprisoned one another in dispute over the crown.

The civil war in “Richard III” was initiated by Richard's father, Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, against King Henry VI of the House of Lancaster. King Henry VI, married to Margaret of Anjou, entrusted his administration to inept personal friends. Richard of York sought to alleviate the ensuing problems. Moreover, he could lay stronger claim to the crown than the reigning king. A series of battles followed. Richard of York was, in fact, placed in power in 1454 and 1455-1456, due to Henry VI's bouts of insanity, and it was decreed that the succession was to pass down to Richard’s line, not Henry’s. Queen Margaret, determined that her son succeed his father, vehemently opposed the Duke. He was killed by her army at Wakefield in 1460.Duke Richard’s son, Edward IV, assisted by Richard of Gloucester, later Richard III, then took up the dispute. Edward IV's victory at Tewkesbury at last secured the crown for the House of York.

The marriage of the Earl of Richmond and Princess Elizabeth, announced at the end of Richard III, brings peace and unity once again to the Houses of Lancaster and York.

DRAMATURGICAL NOTES

THEATRICAL RICHARD: HERO, VILLAIN, AND IRONIC COMEDIAN

Like the historical Richard, Shakespeare's Richard is also legendary. It has been a coveted role for actors through the centuries. The theatrical Richard plainly states that he is "misshapen" and "determined to prove a villain. "Richard’s moral and physical deformity is counter-balanced by the quick wit and charm with which Shakespeare endows him. He is both tenacious and contemptible in his determination to rule. The play emphasizes the political intrigue of Richard's exploits, and allows the drama's human and poetic qualities to develop naturally.

“Richard III”, like “Hamlet”, requires judicious cutting for presentation on the modern stage. For one thing, it is much too long for an evening’s performance. We have attempted to streamline the action our production to produce a “thriller-like” atmosphere, rather than a “pageant-like” historical presentation. By cutting almost 25% of Shakespeare’s text we have focused on the material context of Richard’s rise and inevitable fall. Richard is shown to capitalize, skillfully, brutally and single-mindedly, on the political conflict that surrounds him. At the same time, he is seen as a victim, psychologically and emotionally damaged by the flawed belief structures, expectations and codes of a society rising from civil confusion; flaws which his rise to power both exploited and exposed. This is the end of the Middle Ages and we have not quite entered the Age of Reason or Renaissance.It is a bloody time, the concept of “nationalism” or personal sacrifice for the sake on one’s country has not yet taken hold in the collective consciousness, self-interest lies at the heart of all alliances and no one is above helping his neighbor “across the River Styx” if there is something to be gained by it. There are no “clean hands” – except perhaps for those of the Princes in the Tower.

So how is Richard a hero? The impetus to such consideration is most of all the contradiction that lies in the figure of Richard. On the one hand, he is so repulsive a villain that his punishment in the end causes great satisfaction. On the other hand, though, one has to admit feeling some delight in the genius of his machinations and his absolute ignorance of all morals and authority.

PRODUCTION NOTES

Our production opens with a silent prologue extracted from a scene in Shakespeare’s “Henry VI Part 3” - Gloucester’s murder of the imprisoned King Henry VI - to set the stage. This is followed by the coronation of Edward IV and the beginning of Shakespeare’s “The Tragedy of King Richard III.” We have divided the play into two sections. The first, dealing with Richard’s bloody ascent to the throne is entitled “Richard of Gloucester” and includes the first three acts of Shakespeare’s play. The second, called “King Richard”, follows intermission and chronicles Richard’s brief rule and overthrow on the field of Bosworth.

George Hartpence and director Cheryl Doyle collaborated in editing Shakespeare's text down into a 3 hour working version for use in the "Net's" production. (See attached document below for the working script -with edits visible.) About a dozen minor characters were deleted from the show, thereby decreasing confusion from too much double and triple casting - very important in a play where most of the major characters mentioned share the same surnames - four Richards, three Edwards, two Henrys, two Georges, two Elizabeths, etc. About 25% of the original script was excised, but care was taken to see that only two very minor scenes were deleted in their entirety - the "woe to a land governed by a child" scene in Act 2 between three previously and subsequently unseen citizens, and the forgettable scrivener scene in Act 3. Other scenes were edited and blended to improve the pace and understandability for an audience unfamiliar with the political state in England at the end of The War of the Roses.

The set design is stylized to reflect the decay brought about by the nearly fifty years of civil war known as The War of the Roses. Our costume pieces were chosen to reflect the actual time period, but also to portray a more sinister, “Goth” appearance expressive of the dark nature of much of the action in the play.

Sources:

“Richard III”, The Folger Shakespeare Library General Reader’s Edition.Edited by Louis B. Wright and Virginia A LaMar.

The Tragedy of KING RICHARD III - Synopsis

Multiple murders, serial seductions and a serious shortage of strawberries... Shakespeare's favorite villain-king is back in town ... and looking for his horse.

The ActorsNET of Bucks County presents Shakespeare’s “Richard III”.

THERE WERE THREE KINGS OF ENGLAND NAMED RICHARD. One was a butcher who killed hundreds in one day; one was an irresolute tyrant who was deposed by his own men. The last had the throne for just a few years, but traded it at his death for another: He is the monarch of villains, the most enduring evildoer in Western literature, and perhaps the best known.

As Shakespeare envisioned it, upon the death of King Henry VI, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, believes himself to be the most qualified to rule. However, his brother, Edward, is first in succession and is, therefore, crowned King Edward IV. Richard devises a brutal stratagem to ascend the English throne. He callously executes family, friends, and subjects. By 1483 the sceptre, at last, is his. But in 1485, the Earl of Richmond at the bloody battle of Bosworth Field confronts Richard. Richmond, a distant cousin from another branch of the family, kills Richard and assumes the throne.

Richard was the last British monarch to take to the field in battle – for now obvious reasons. Richmond was crowned King Henry VII and married Princess Elizabeth, Richard's niece and daughter of the late King Edward IV. Together, Henry and Elizabeth founded the Tudor dynasty of English monarchs.

In the first scene of the play, Richard announces in a soliloquy his plan to be king. With his elder brother, King Edward IV, dying, Richard hires two murderers to kill his other brother George, Duke of Clarence – an obstacle he must o`erleap on his way to the crown. When the king dies, Richard becomes "Lord Protector" of the new heirs, the king's young sons. Anxious to "protect" his own interests, Uncle Richard imprisons them in the tower.

Aided by the Duke of Buckingham, a powerful political ally, Richard executes the family of the late king's wife, Queen Elizabeth, who naturally would prefer to see her son on the throne. To further discredit his brother, Richard circulates rumors that the previous king and his sons are illegitimate – Edward by parental indiscretion, and his children because of his failure to fulfill his oath to marry two previous fiances, thus rendering his marriage to Elizabeth Woodeville invalid.(At that time being betrothed carried all the responsibility and commitment of marriage itself.)To increase public support for his own claim to the crown, Richard enacts shows of humility, devotion, kindness, and other virtues which recommend him to the citizenry, and especially to the Lord Mayor and aldermen of London.

Finally, having staged the offer himself, Richard accepts the "golden yoke of sovereignty. "Unjustifiably convinced that his position is threatened, he "terminates" the princes in the tower, poisons his wife, Lady Anne, and arranges to marry Princess Elizabeth, daughter of the former king, Edward IV. Even Buckingham, without whom he would not have secured the crown, is executed, so paranoid has Richard become.

Eventually, Richard's real enemies combine forces to overthrow him. Thus, despite a torrent of plots, a web of intrigue, and a long and infamous trail of blood, his reign is over after only two years.