The Tragedy of MACBETH by Wm Shakespeare

George has been involved in four separate productions of "The Scottish Play"... very nearly five.

Macbeth (1996) was my first major Shakespearean lead role & "the curse" let its full effect be felt for the 2007 production - the run had to be postponed 2 months to allow me to recover from torn calf muscles that occurred during rehearsal.

MACBETHs

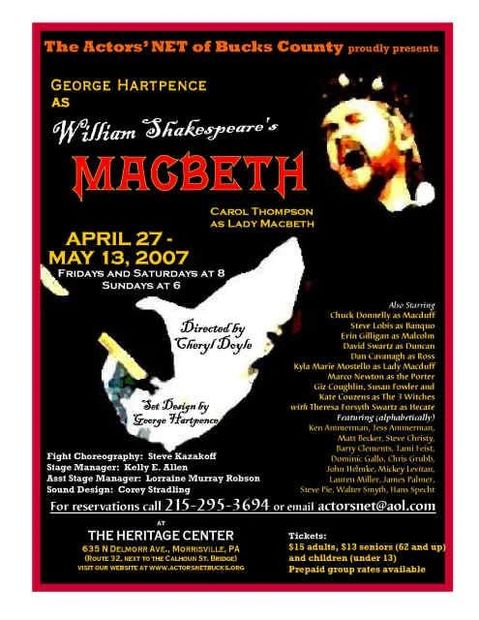

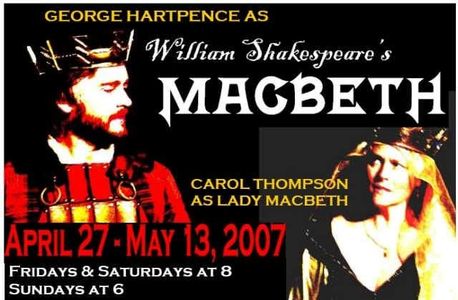

ActorsNET (2007)

Players Club of Swarthmore (2000)

Circle Players (2003)

directed by Cheryl Doyle

April 27 - May 13, 2007

George Hartpence as Macbeth

Carol Thompson as Lady Macbeth

Steve Lobis as Banquo

Chick Donnelly as Macduff

Circle Players (2003)

Players Club of Swarthmore (2000)

Circle Players (2003)

directed by Rob Pherson

staged reading

December 2003

George Hartpence as Macbeth

(the one that got away - all rehearsals went smoothly, inclement weather forced postponement of the performance & schedule conflicts lead to cancellation)

Players Club of Swarthmore (2000)

Players Club of Swarthmore (2000)

Players Club of Swarthmore (2000)

directed by Bhoden Senkow

October 19 - November 4, 2000

George Hartpence as Macduff

Steve Gleich as Macbeth

Shakespeare`70 (1999)

The College of New Jersey (1996)

Players Club of Swarthmore (2000)

directed by Frank Erath

June 10 - 19, 1999

George Hartpence as Caithness (one night appearance)

The College of New Jersey (1996)

The College of New Jersey (1996)

The College of New Jersey (1996)

directed by Hal Hogstrom

April 1996

George Hartpence as Macbeth

Janet Quartarone as Lady Macbeth

Dale Simon as Banquo

Walt Cupit as Macduff

MACBETH (2007) at ActorsNET

directed by Cheryl Doyle

April 27 - May 15, 2007

George Hartpence as Macbeth

and Carol Thompson as Lady Macbeth

Also Starring:

Chuck Donnelly as Macduff

Steve Lobis as Banquo

Erin Gilligan as Malcolm

Dan Cavanagh as Ross

Kyla Marie Mostello as Lady Macduff

David Swartz as Duncan

Giz Coughlin, Kate Couzens, Susan Fowler as the Three Wierd Sisters

and Theresa Forsyth Swartz as Hecate

Featuring (alphabetically):

Ken Ammerman, Tess Ammerman, Liz Bartlett, Matt Becker, Barry Clements, Tami Feist, Dominic Gallo, John Helmke, Mickey Levitan, Lauren Miller, J.J. Newberry, Marco Newton, James Palmer, Steve Pie, Neil Pirozzi, Tom Smith, and Hans Specht!

Fight Choreography by Steve Kazakoff

Set Design by George Hartpence

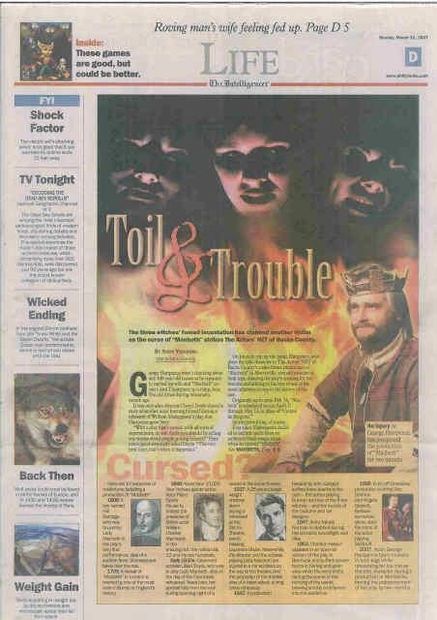

The Curse of the "Scottish Play" Lives!

Great press, but oh the pain!

The Curse Lives!

Originally slated to follow hot on the heels of their January production of “The Crucible,” the 2007 ActorsNet mid-February production of “Macbeth” unfortunately fell prey to the curse of the Scottish Play and had to be postponed for two months while its lead player recuperated from torn calf muscles sustained during rehearsal.

Doylestown Intelligencer article by Andy Vineberg about "the curse" at ActorsNet:

TOIL & TROUBLE

"The three witches’ famed incantation has claimed another victim as the curse of "Macbeth" strikes the Actors'Net of Bucks County.

read the full Doylestown Intelligencer article

MACBETH (2007) Production Photos

Act I sc ii The bloody sergeant (Ken Ammerman) informs King Duncan (David Swartz) of Macbeth's feats on the battlefield.

MACBETH (2000) at Players Club of Swarthmore

George Hartpence as Macduff

directed by Bhoden Senkow

October 19 - November 4, 2000

featuring Steve Gleich as Macbeth, Kathleen Coll Senkow as Lady Macbeth,

and Carol Thompson as Lady Macduff and one of the Wierd Sisters.

Photo Gallery

George Hartpence (left) as Macduff and Dennis Smeltzer (right) as Malcolm

MACBETH (1999) with Shakespeare`70

directed by Frank Erath - June 10th thru 19th, 1999

The second production of the Scottish play in which I appeared was an informal walk-on for Shakespeare`70's 1999 production at the Open Air Theater in Washington Crossing Park directed by Dr. Frank Erath. I was offered a principal role in the production, but wasn't able to accept a commitment for the entire run - due to the death of my first wife a month earlier. However, "for fellowship" with the company I did a one night walk-on as Caithness.

It featured Steve Kazakoff as Macbeth and Carol Kehoe as Lady Macbeth, Dale Simon appeared as Banquo and Tom Moffit played Macduff.

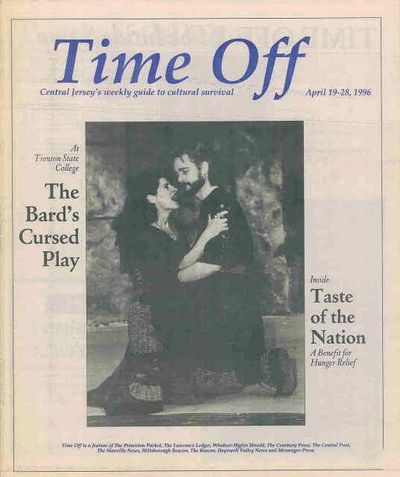

MACBETH (1996) at The College of New Jersey

directed by Professor Hal Hogstrom - April 1996

The first production of The Scottish play in which I appeared was for Professor Hal Hogstrom at The College of New Jersey (then Trenton State College) in 1996.

I appeared as Macbeth along with Janet Quartarone as his fiend-like queen (Lady Macbeth), Dale Simon as Banquo, Walt Cupit as Macduff, and Brian Bara as Ross. It was George's first major lead in a Shakespearean production.

The rest of the cast consisted of college students, alumni and advisers.

cover of the Princeton Packet weekend "TimeOff" entertainment supplement

cover picture features Janet Quartarone as Lady Macbeth welcoming her warlord husband home from the wars (Act I sc v)

and George Hartpence as Macbeth.

quotes from George Hartpence used in the article:

"... Macbeth really is a tragic hero, a murderer with a conscience..."

"He is a powerful man caught in a morality play. He makes one false step, and then everything steamrolls from there."

"We see him disintegrate before our eyes."

read TimeOff feature article

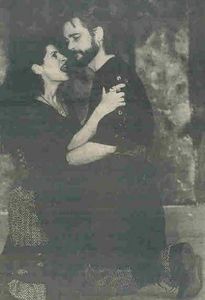

Janet Quartarone as Lady Macbeth and George Hartpence as Macbeth

Poster graphics by Dale Simon

Photo Gallery

Janet Quartarone as Lady Macbeth welcomes her husband home from the wars. George Hartpence as Macbeth

MACBETH (1996) poster artwork by Dale Simon

Dramatis Personae

MACBETH: KINGCRAFT AND WITCHCRAFT

notes compiled for the 2007 production

Dr. Clare Jackson is Lecturer and Director of Studies in History at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, and the author of Restoration Scotland 1660-1690. Royalist Politics, Religion and Ideas (2003). In Macbeth, Kingcraft and Witchcraft, she explains how the play, Macbeth, might have been interpreted by an early 17th-century audience and especially the ways in which kingship and witchcraft could be seen as mutual competitors for supernatural influence.

The “Divine Right of Kings”:

Shakespeare’s Macbeth presents theatregoers with an absorbing drama of kingship, tyranny, usurpation and regicide. Composed around 1606, Macbeth was performed before the reigning British monarch, James VI & I, who held notoriously specific views about kingship and had written extensively on the theory and practice of royal governance. As James VI of Scotland, he had published two works expounding his belief in the ‘divine right of kings’ before coming to the English throne on Queen Elizabeth’s death in 1603. In The True Law of Free Monarchies (1598) and Basilicon Doron (1599), James insisted that monarchs were divinely-ordained and served as God’s representatives on earth. At the same time, however, James recognized a compelling ideological correlation between divinely-ordained monarchy and diabolic prophecy. A monarch who claimed, as James VI & I did, to be the Lord’s Anointed, inevitably became the Devil’s most potent enemy. Promoting kingcraft also entailed confronting witchcraft.

Scotland’s bloody history:

In choosing to write a play about Scottish kingship, Shakespeare had to tread sensitively to avoid provoking royal censure, whilst also appealing to an English audience that tended to regard Scotland as an alien, primitive and barbarous backwater. Such popular prejudice was, to some extent, confirmed by the violent and volatile period of medieval Scottish history in which Macbeth is set. Whilst Macbeth ruled Scotland for seventeen years (1040-1057 AD), of his nine royal predecessors who ruled between 943 and 1040, seven were murdered, either by their successors or in royal feuds. The life expectancy of Scots monarchs was correspondingly short. Since Robert III’s accession in 1390, every Scots monarch had succeeded to the throne as a minor, leading to destabilizing royal regencies and endemic noble rivalries. James VI had himself been crowned in July 1567, when he was only thirteen months old. His coronation followed the vicious assassination of his father, Henry, Lord Darnley, and the forced abdication and imprisonment of his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, who later escaped to English exile, before being executed by Queen Elizabeth in 1587.

King James and Witchcraft:

An aspect of Jacobean kingship theory that would have exerted a particular fascination for a seventeenth-century audience of Macbeth is the relationship between kingcraft and witchcraft. As a divinely-ordained monarch, James acknowledged a sacred duty to prosecute all witches who subversively tried to replace his divine authority in earthly affairs with diabolic influence. In 1597, James published a treatise entitled Daemonology, in which he argued that the potential for witches to harm a monarch varied in direct proportion to that monarch’s vigilance on the grounds that ‘God is very able to make them instruments to waken and punish his sloth’. James had personally presided over a series of witchcraft trials held near Edinburgh, at which over a hundred suspected witches were examined between November 1590 and May 1591, of whom a large number were convicted and put to death. Charges leveled against the suspected witches included treasonable acts directed against James himself, including attempted regicide by melting waxen royal effigies, as well as raising the tempestuous gales that had delayed James and his Danish bride, Anne, from returning to Scotland in the spring of 1590.

Performance History of Macbeth

Evidence suggests that Macbeth was written by command as one of the plays to be given before King James I and the King of Denmark during the latter’s notable visit to England in the summer of 1606. Shakespeare’s company was the King’s Players, and it would be natural for them to be commanded to produce a story of Scottish history touching on the ancestry of their patron. The title role was created by the great Richard Burbage and his infamous queen by the boy-actress Edmans. The play was first printed in the Folio of 1623, where the text shows some signs of cutting and alteration. The lyrical episodes of Hecate and the witches (III, 5 and IV, 1) are thought to have been added by another playwright.

When Charles II ascended the British throne in 1660, he assigned Macbeth to William Davenant and the Duke’s Company. Not content to produce the play in its original form, Davenant altered the work considerably to indulge his two favorite hobbies. The first was his desire for operatic and scenic splendor; the second, his pursuit of structural balance. The first he obtained by elaborating the witches’ scenes, introducing all kinds of dancing, singing, and gibberish, some of it taken from Middleton’s The Witch. The second was achieved by amplifying the role of Lady Macduff, for whom he created numerous scenes between her and her lord symmetrically opposed to the bits between Macbeth and his wicked wife. Macduff’s virtuous lady inveighs to him against ambition. Lady Macbeth is given a new scene in which she is haunted by the ghost of Duncan, which induces her to try to persuade Macbeth to give up ambition and the crown. Davenant’s bastardization, with Thomas Betterton in the title role, drove Shakespeare’s original from the stage until 1744.

It was David Garrick who, during his management of the Drury Lane Theatre (1742-1776), revived Macbeth as written by Shakespeare, playing the title role there every season except four. Although he kept Davenant’s operatic witch scenes, he omitted the spurious Lady Macduff scenes, along with her infamous murder scene (IV, 2) and the bit with the Porter (II, 3). He could not resist writing a new climactic speech for Macbeth, in which the hero-villain mentions, with his dying breath, his guilt, delusion, the witches, and horrid visions of future punishment. Garrick and his leading lady, Hannah Pritchard, introduced a natural style of acting and became famous as the tortured hero and heroine. So urgent was Garrick’s delivery that in one performance when he told the First Murderer “There’s blood upon thy face,” the actor in question involuntarily replied, “Is there, by God?”

The next famous pair to assay these roles were John Philip Kemble (1757-1823) and his talented sister, Sarah Siddons, at Drury Lane in the season of 1784 and for many years thereafter. Siddons made an extraordinary innovation when in the sleep-walking scene she put the candle down, defying the tradition of carrying the candle throughout. J. Boaden recorded in her Memoirs (1827), “She laded the water from the imaginary ewer over her hands-bent her body to listen to the sounds presented to her fancy, and hurried to resume the taper where she had left it, that she might with all speed drag her husband to their chamber.” Her delivery of several lines has become legendary: the long pause on “made themselves-air,” the sudden energy on “shalt be what thou art promised,” the association of “my spirits in your ear” with the spirits she has just invoked, and the downward and decisive inflection on “We fail.” Siddons imagined the character as a fragile and delicate blonde who subdued Macbeth by the dual exercise of intellect and beauty, moved by the memory of her father and the babe to whom she had “given suck.” She achieved every part of the role except the blonde fragility, which was beyond her stately, statuesque appearance.

William Charles Macready proved a workmanlike Macbeth in his revival of 1837, which featured new scenic effects and innovative staging. John Bull recorded his admiration of the scene in which the murder of Duncan is discovered, and the march of the army from Birnam Wood. “In the latter each man was completely screened by the immense bough he carried; and the scenic illusion by which a whole host was represented stretching away into the distance, and covered as by one leafy screen, which was removed at the same time that the soldiers in the foreground threw down theirs, had all the reality of a dioramic effect.” Macready himself made memorable several moments: his imperious command to the witches-“Stay and speak,” his desperate recoil from Banquo’s ghost, the dropping of his truncheon on hearing that Lady Macbeth is dead, his half-drawn sword over the messenger who announces the approach of Birnam Wood, and the remarkable energy of the fight in which he died.

Samuel Phelps (1804-1878) is credited with removing the last vestiges of adaptation from Macbeth during his management of Sadler’s Wells between 1844 and 1862. Unlike his contemporaries, who rearranged the play to avoid scene shifts and made drastic cuts to allow scope for spectacle, Phelps made only minor cuts and transpositions.

Charles Kean and his wife Ellen Tree staged a spectacular, long-running Macbeth at the Princess’s Theatre in 1853, famed for its historically accurate scenery and costumes. Kean apparently turned in a performance considerably less ferocious than his wife’s. The Leader reported, “When the witches accost him, his only expression of ‘metaphysical influence’ is to stand still with his eyes fixed and his mouth open ... In Charles Kean’s Macbeth all tragedy has vanished; sympathy is impossible, because the mind of the criminal is hidden from us. He makes Macbeth ignoble, with perhaps a tendency towards Methodism.”

The last great pair of the 19th Century were Henry Irving and Ellen Terry at the Lyceum Theatre in 1874 and later in 1889. Terry’s Lady Macbeth was less fearsome than sympathetic, according to The Times. “Her matted red hair, hanging in long tresses, and her ruddy cheeks mark her as a raw-boned daughter of the North, and she wears an appropriate dress of garish green stuff embroidered with gold. There is nothing of the martial or adventurous spirit in her composition to bring her into harmony with her barbarous surroundings. On the contrary, she is a woman of warm sympathies living in the tenderest relation with her husband.”

The 20th Century saw numerous great revivals, especially Orson Welles’ “Voodoo” Macbeth at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem (1936), Margaret Webster’s famous production with Maurice Evans and Judith Anderson (1941) which set a standard for decades to come, and Glen Byam Shaw’s Royal Shakespeare Theatre production with Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh (1955). Kenneth Tynan argued that in the role of Macbeth Olivier “shook hands with greatness,” and proclaimed the performance “a masterpiece: not of the superficial, booming, have-a-bash kind, but the real thing, a structure of perfect forethought and proportion, lit by flashes of intuitive lightning.” Trevor Nunn (1972) tackled the play at The Other Place, the RSC’s studio theatre in Stratford, with Ian McKellen as Macbeth and Judi Dench playing Lady Macbeth in a version that was later deemed definitive. Reportedly produced with a budget of only £250, scenery and lighting were kept to a minimum. Actors sat on upturned crates outside the playing space, a Brechtian chalk circle. Adrian Noble (1993) directed an RSC production with Derek Jacobi and Cheryl Campbell. Jacobi’s consummately military Macbeth was praised as one of those highly trained, sensitive military men who love the army for its discipline and order. Campbell’s Lady Macbeth performance was praised for its paradoxical power. Her Lady Macbeth was a woman consumed by her own ambition, “a woman discovering not only her own power but also the sapping of her nature by that very power.” Gregory Doran directed Macbeth in the Swan Theatre in 1999. Hailed as the RSC's "best Macbeth since Trevor Nunn's legendary production a quarter of a century ago," the fast-moving production presented Macbeth (played by Antony Sher) as a dynamic warrior/military dictator driven insane by his lust for power. Set in a militaristic state, the production drew parallels with the Balkan conflict and the Ceaucescu regime in Romania.

The “Curse”

The lore surrounding Macbeth and its supernatural power begins with the play’s creation in 1606. According to some, Shakespeare wrote the tragedy to ingratiate himself to King James I, who had succeeded Elizabeth I only a few years before. In addition to setting the play on James’ home turf, Scotland, Will chose to give a nod to one of the monarch’s pet subjects, demonology (James had written a book on the subject that became a popular tool for identifying witches in the 17th century). Shakespeare incorporated a trio of spell-casting women into the drama and gave them a set of spooky incantations to recite. Alas, the story goes that the spells Will included in Macbeth were lifted from an authentic black-magic ritual and that their public display did not please the folks for whom these incantations were sacred. Therefore, they retaliated with a curse on the show and all its productions.

Those doing the cursing must have gotten an advance copy of the script or caught a rehearsal because legend has it that the play’s infamous ill luck set in with its very first performance. John Aubrey, who supposedly knew some of the men who performed with Shakespeare in those days, has left us with the report that a boy named Hal Berridge was to play Lady Macbeth at the play’s opening on August 7, 1606. Unfortunately, he was stricken with a sudden fever and died. It fell to the playwright himself to step into the role.

It’s been suggested that James was not that thrilled with the play, as it was not performed much in the century after. Whether or not that’s the case, when it was performed, the results were often calamitous. In a performance in Amsterdam in 1672, the actor in the title role is said to have used a real dagger for the scene in which he murders Duncan and done the deed for real. The play was revived in London in 1703, and on the day the production opened, England was hit with one of the most violent storms in its history.

As time wore on, the catastrophes associated with the play just kept piling up like Macbeth’s victims. At a performance of the play in 1721, a nobleman who was watching the show from the stage decided to get up in the middle of a scene, walk across the stage, and talk to a friend. The actors, upset by this, drew their swords and drove the nobleman and his friends from the theatre. Unfortunately for them, the noblemen returned with the militia and burned the theatre down. In 1775, Sarah Siddons took on the role of Lady Macbeth and was nearly ravaged by a disapproving audience. It was Macbeth that was being performed inside the Astor Place Opera House the night of May 10, 1849, when a crowd of more than 10,000 New Yorkers gathered to protest the appearance of British actor William Charles Macready. (He was engaged in a bitter public feud with an American actor, Edwin Forrest.) The protest escalated into a riot, leading the militia to fire into the crowd. Twenty-three people were killed, 36 were wounded, and hundreds were injured. And it was Macbeth that Abraham Lincoln chose to take with him on board the River Queen on the Potomac River on the afternoon of April 9, 1865. The president was reading passages aloud to a party of friends, passages which happened to follow the scene in which Duncan is assassinated. Within a week, Lincoln himself was dead by a murderer’s hand.

In the last 135 years, the curse seems to have confined its mayhem to theatre people engaged in productions of the play.

· In 1882, on the closing night of one production, an actor named J. H. Barnes was engaged in a scene of swordplay with an actor named William Rignold when Barnes accidentally thrust his sword directly into Rignold’s chest. Fortunately a doctor was in attendance, but the wound was supposedly rather serious.

· In 1926, Sybil Thorndike was almost strangled by an actor.

· During the first modern-dress production at the Royal Court Theatre in London in 1928, a large set fell down, injuring some members of the cast seriously, and a fire broke out in the dress circle.

· In the early Thirties, theatrical grande dame Lillian Boylis took on the role of Lady Macbeth but died on the day of final dress rehearsal. Her portrait was hung in the theatre and some time later, when another production of the play was having its opening, the portrait fell from the wall.

· In 1934, actor Malcolm Keen turned mute onstage, and his replacement, Alistair Sim, like Hal Berridge before him, developed a high fever and had to be hospitalized.

· In 1936, when Orson Welles produced his “voodoo Macbeth,” set in 19th-century Haiti, his cast included some African drummers and a genuine witch doctor who were not happy when critic Percy Hammond blasted the show. It is rumored that they placed a curse on him. Hammond died within a couple of weeks.

· In 1937, a 30-year-old Laurence Olivier was rehearsing the play at the Old Vic when a 25-pound stage weight crashed down from the flies, missing him by inches. In addition, the director and the actress playing Lady Macduff were involved in a car accident on the way to the theatre, and the proprietor of the theatre died of a heart attack during the dress rehearsal.

· In 1942, a production headed by John Gielgud suffered three deaths in the cast—the actor playing Duncan and two of the actresses playing the Weird Sisters—and the suicide of the costume and set designer.

· In 1947, actor Harold Norman was stabbed in the swordfight that ends the play and died as a result of his wounds. His ghost is said to haunt the Colliseum Theatre in Oldham, where the fatal blow was struck. Supposedly, his spirit appears on Thursdays, the day he was killed.

· In 1948, Diana Wynard was playing Lady Macbeth at Stratford and decided to play the sleepwalking scene with her eyes closed; on opening night, before a full audience, she walked right off the stage, falling 15 feet. Amazingly, she picked herself up and finished the show.

· In 1953, Charlton Heston starred in an open-air production in Bermuda. On opening night, when the soldiers storming Macbeth’s castle were to burn it to the ground onstage, the wind blew the smoke and flames into the audience, which ran away. Heston himself suffered severe burns in his groin and leg area from tights that were accidentally soaked in kerosene.

· In 1955, Olivier was starring in the title role in a pioneering production at Stratford and during the big fight with Macduff almost blinded fellow actor Keith Mitchell.

· In a production in St. Paul, Minnesota, the actor playing Macbeth dropped dead of heart failure during the first scene of Act III.

· In 1988, the Broadway production starring Glenda Jackson and Christoper Plummer is supposed to have gone through three directors, five Macduffs, six cast changes, six stage managers, two set designers, two lighting designers, 26 bouts of flu, torn ligaments, and groin injuries. (The numbers vary in some reports.)

· In 1998, in the Off-Broadway production starring Alec Baldwin and Angela Bassett, Baldwin somehow sliced open the hand of his Macduff.

Add to these the long list of actors, from Lionel Barrymore in the 1920s to Kelsey Grammer in the 2000, who have attempted the play only to be savaged by critics as merciless as the Scottish lord himself.

To many theatre people, the curse extends beyond productions of the play itself. Simply saying the name of the play in a theatre invites disaster. (You’re free to say it all you want outside theatres; the curse doesn’t apply.) The traditional way around this is to refer to the play by one of its many nicknames: “the Scottish Play,” “the Scottish Tragedy,” “the Scottish Business,” “the Comedy of Glamis,” “the Unmentionable,” or just “That Play.” If you do happen to speak the unspeakable title while in a theatre, you are supposed to take immediate action to dispel the curse lest it bring ruin on whatever production is up or about to go up. The most familiar way, as seen in the Ronald Harwood play and film The Dresser, is for the person who spoke the offending word to leave the room, turn around three times to the right, spit on the ground or over each shoulder, then knock on the door of the room and ask for permission to re-enter it. Variations involve leaving the theatre completely to perform the ritual and saying the foulest word you can think of before knocking and asking for permission to re-enter. Some say you can also banish the evils brought on by the curse simply by yelling a stream of obscenities or mumbling the phrase “Thrice around the circle bound, Evil sink into the ground.” Or you can turn to Will himself for assistance and cleanse the air with a quotation from Hamlet:

Angels and Ministers of Grace defend us!

Be thou a spirit of health or goblin damn’d,

Being with thee airs from heaven or blasts from hell,

Be thy intents wicked or charitable,

Thou comest in such a questionable shape that I will speak to thee.

The Historical Macbeth

Macbeth, (1005 – 1057), king of Scotland (1040–57). He succeeded his father as governor of the province of Moray c.1031 and was a military commander for Duncan I. In 1040 he killed Duncan in battle and seized the throne. Possibly of royal descent himself, he acquired a direct claim to the throne through his wife, Gruoch; she was a granddaughter of Kenneth III, who had been overthrown by Duncan's ancestor Malcolm II. Macbeth represented northern elements in the population who were opposed to the ties with the Saxons advocated by Duncan. Scotland prospered under Macbeth and he visited Rome in 1050. The remains of Macbeth's hill top fortress Dunsinane lays just east of Strathearn, in Perthshire in central Scotland. Macbeth was defeated at Dunsinane in 1054 by Siward, earl of Northumbria, who regained the southern part of Scotland on behalf of Malcolm Canmore, Duncan's son. Malcolm himself regained the rest of the kingdom after defeating and killing Macbeth in the battle of Lumphanan in 1057. He then succeeded to the throne as Malcolm III. William Shakespeare's version of the story comes from the accounts of Raphael Holinshed and Hector Boece. Banquo (Banquho, "Thane of Lochabar") and Fleance are supposed to be the ancestors of the Stewarts (Stuarts), including some kings of Scotland and later Scotland-and-England. After Banquo's murder by Macbeth's assassins, Fleance fled to North Wales, and married one Nesta / Mary, daughter of Gryffudth ap Llewellyn, Prince of Wales. Walter the Steward, first "High Steward of Scotland" and the historical founder of the Stewart line, was supposedly their son. However, Walter's real name was "Walter Fitz Alan Dapifer", son of Alan Dapifer, the sheriff of Shropshire. The sheriff was the son of some ordinary folks. For some reason, perhaps to give his own Stuart king some more glamorous ancestors, Boece made up Banquo and Fleance.

Additional Sources:

Richard Huggett’s Supernatural on Stage: Ghosts and Superstitions in the Theatre (NY, Taplinger, 1975).

Roz Symon, RSC’s Macbeth play Guide, 2004: http://www.rsc.org.uk/macbeth/home/home.html

Robert Faires, The Curse of the Play, Austin Chronicle, October 123, 2003