CANDIDA by G.B. Shaw & THE CONSTANT WIFE by W. Somerset Maugham

CANDIDA by George Bernard Shaw

role: Rev. James Mavor Morell

Directed by Mort Paterson

an ActorsNET of Bucks County Production

October 28 - November 13, 2011

with

Carol Thompson as Candida Morell

George Hartpence as Rev James Mavor Morell

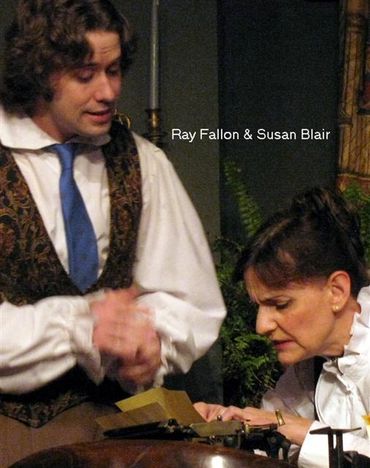

Ray Fallon as Eugene Marchbanks

Susan Blair as Prossy

David Swartz as Mr. Burgess

Fred Halperin as Lexy

Candida, a classic comedy of the modern English-language theater, was written in 1894 by George Bernard Shaw, the prolific Irish-born dramatist who became one of the most widely-produced playwrights of the twentieth century.

Critical Praise for this production:

Packet Publications' Time Off, critic Bob Brown notes that The NET has a "near-perfect ensemble" performing George Bernard Shaw's Candida. He writes, "All the actors in this production, directed by seasoned professional Mort Paterson, are pitch perfect. Ms. Thompson and Mr. Hartpence, familiar in regional theatre productions, play particularly well off each other. Ms. Thompson's Candida is a woman confidently in control." Mr. Brown has high praise for the rest of the cast -- Ray Fallon, David Swartz, Susan Blair and Fred Halperin -- as well.

As for the play, Mr. Brown writes, "Candida is a lighthearted, amusing probe of our assumptions about love and marriage, and about the effects of impulsive attraction....This is a very entertaining production, well handled all around by a talented cast and production crew."

Carol Thompson as Candida

Set in London's East End during the Victorian era, Candida is about the domestic turmoil that ensues when an impetuous young poet comes between a progressive-minded clergyman and his charismatic wife. Though the story is centered on a classic romantic triangle, the questions it raises about the nature of love, fidelity, and the imagination of the artist are as provocative and enduring as ever, thanks to Shaw's vigorous wit and argumentative spirit.

Cast Photos

Cast List

Plot Summary

Carol Thompson as Candida and George Hartpence as Rev. James Morell

The play begins in October of 1894 in the drawing room of St. Dominic's parsonage in the East End of London. Reverend James Morell, a Christian Socialist minister, discusses his busy schedule with his efficient typist, Miss Proserpine Garnett ("Prossy").

Burgess, Morell's father-in-law, a successful but unscrupulous businessman from a working class background, visits the Morell home for the first time in three years. While Burgess cannot convince Morell that he has changed his nature, he impresses Morell with the news that he has raised the wages of his underpaid workers. Morell's wife Candida returns home accompanied by the 18 year-old poet Eugene Marchbanks, whom Morell has recently rescued from the streets. Once alone with Morell, Marchbanks reveals that he is in love with Candida. His nervousness fades as he speaks of Candida's beauty and how Morell does not deserve her. As Act One ends, the Reverend Morell, shaken by Marchbanks' accusation, nonetheless insists that the young man stay for lunch.

At the start of Act Two, Marchbanks is left alone with the typist Prossy. While she tries to work, he speaks of the plight of the poet and attempts to get her to confess her ardor for Morell. Flustered by Eugene's insinuations, she strikes out instead at Burgess, who has wandered in, accusing him of being a "silly old fathead."

Meanwhile, Candida senses her husband's growing discomfort on the subject of Marchbanks and pulls him aside to talk. She tries to tease him but ends up reinforcing his insecurities about their marriage and his vocation. Candida suggests that his popularity as a speaker has more to do with his personal charm than his message. Frustrated, Morell considers canceling his evening's speaking appointment. He reconsiders, though, and decides to leave Candida alone with Marchbanks as a kind of test.

At the top of Act Three, Marchbanks and Candida near the end of their evening together - an evening spent in poetry reading. Seeing that Candida is bored with the verse, Marchbanks is on the verge of declaring his love when Morell arrives home. Morell and Marchbanks size each other up, and Morell insists that Candida choose between the two of them. Candida takes up the challenge, asking each man to make his case. They do, and Candida, in a surprising turn of events, demonstrates that Morell is the weaker of the two, and therefore more deserving of her love. Marchbanks, realizing his future lies elsewhere, leaves Morell and Candida behind.

Carol Thompson as Candida, Ray Fallon (kneeling) as Eugene & George Hartpence as Rev. Morell

David Swartz as Mr. Burgess - Candida's father

CANDIDA Preview Photos

Fred Halpern as Lexy, Susan Blair as Prossy, and George Hartpence as Morell

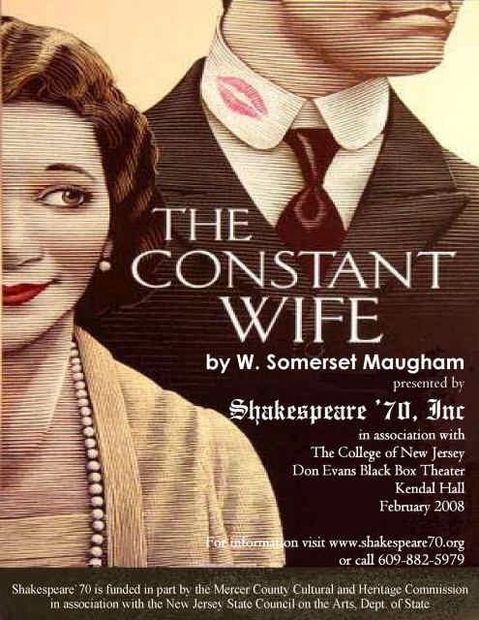

THE CONSTANT WIFE by W. Somerset Maugham

Carol Thompson as Constance Middleton & George Hartpence as John Middleton

a Shakespeare`70 production

February 14 thru 24th, 2008

presented in the Don Evans Black Box Theater

on the campus of The College of New Jersey

Carol Thompson as Constance Middleton

"The Constant Wife" plot synopsis

by Dr. Roberta E. Zlokower

(in reference to the 2005 Roundabout Theater Company production)

The Constant Wife, a comedy of manners, set in a 1926 London drawing room, decorated in the finest floral fabrics and green lacquered Chinoiserie, performed with the finest of British accents and mannerisms, and illustrating the chic, fine fashions of the era, concerns the known and unknown relationships of a prissy and proud mother of a daughter, “well-married” to a surgeon, the “well-married” wife, a business tycoon and his wife (who happens to be the surgeon’s lover), an international financier, the financier’s old flame (who happens to be the surgeon’s wife), a sophisticated “spinster” sister, and a successful businesswoman (interior decorator). A butler, named Bentley, (reincarnated as the maid Edith for this S`70 production) rounds out this British cast of characters.

But, this is neither Feydeau nor Moliere, with French doors opening and closing and lovers hiding in closets. This is a British play of fashionable and fascinating language, with the action, repressed as it may be (one set, and it’s the very polished drawing room), mostly in one’s imagination. We might be shocked, not by the marital infidelities and bold behavior, but by the concept that in 1926 Maugham wrote such a modern play of a woman’s right to equality through financial freedom. That financial freedom would come from accepting an offer to join a small decorating firm and the resulting opportunity to pay her husband for her “keep”.

George Hartpence as John Middleton, FRSC

CRITICAL PRAISE

Review by Anita Donovan for The Trenton Times

"Constant Wife" Dazzles

"... the show is a must-see for theater buffs and/or students of cultural change."

"... in the last analysis, this is Constance's play, and Carol Thompson carries it off with spirit."

"Her Constance is constant indeed, full of tolerance, humor, with and generosity of spirit."

The Signal - TCNJ campus student newspaper:

"Constant Wife delivers Constant Laughter"

by Caroline Russomanno (excerpts)

While the play was a company effort, a few of the actors' performances stuck out from the crowd.

Carol Thompson was a pure joy as Constance. She is one of those actresses who delivers a line and it takes the audience a moment to realize it's a terribly funny joke because she said it with such a straight face. "I think husbands and wives tell each other far too much nowadays," she said after discovering her husband's infidelity. Her stage presence and smile lightened an already luminous play.

George Hartpence, playing Carol Thompson's husband John Middleton, was funniest when he wasn't speaking. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then his facial expressions are worth a million.

Tracy Hawkins was the perfect sarcastic but caring mother as Mrs. Culver. She had some of the best lines in the play, including her philosophy on telling whether one is in love with a man or not: "Could you use his toothbrush?"

Recent College graduate Gina Yanuzzi, who played Martha Culver, Constance's unruly but worried sister, was annoying enough to leave little doubt that she was, in fact, Constance's little sister. Meanwhile Heather Duncan, sophomore English major, didn't have a large role as the Middletons' maid, Edith, but her scene dragging luggage across the floor was one of the funniest in the play.

CAST and CREW

THE CONSTANT WIFE - Act I - The Middleton Household

Tracy Hawkins (left) as Mrs. Culver & Gina Yanuzzi (right) as Martha Culver

THE CONSTANT WIFE - Act II - a fortnight later

Dale Simon (right) as Bernard Kersal and Gina Yanuzzi (left) as Martha Culver

THE CONSTANT WIFE - Act III - 11 months later

Constance discusses her Italian holiday plans. Gina Yanuzzi (left) as Martha, Celeste Bonfante (right) a Barbara, Carol Thompson (center) as Constance

Programme Notes compiled for the Shakespeare`70 production

The Author

W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM (1874-1965), though now better known as a novelist and short-story writer, was one of the world's most successful playwrights in the first third of the twentieth century. A prolific writer, Maugham produced some thirty plays, nineteen novels, numerous short stories, and some highly-regarded travel books and memoirs. His detached satirical tone and his skill at story-telling often invited film adaptations: over 100 movies and TV series have been based on Maugham's works, including his most famous novels Of Human Bondage (1915), The Moon and Sixpence (1919), Cakes and Ale (1930) and The Razor's Edge (1944). In fact, his best-known dramatic character came from a short story that others adapted to the stage and screen, Miss Sadie Thompson in "Rain" (1921). Maugham, too, habitually adapted his stories into plays, and vice versa.

Though Maugham took medical training, he knew in his teens that he wanted to be a writer. He loved the theatre, and he began writing novels because he thought it would be good training in how to write plays. His first novel, Liza of Lambeth (1897), drew on his experiences as a medical intern among London's poor, and attracted the attention of Henry Arthur Jones, one of the most successful playwrights of the day. Maugham later fell in love with Jones's daughter Sue, and had an eight-year affair with her that ended only when he finally proposed marriage. In 1915 he had a daughter by Syrie Wellcome, whom he married two years later, but his subsequent relationships were mostly with men.

Maugham's first produced plays, beginning with A Man of Honour in 1904, were mainly witty comedies set among the aristocracy, structured as "well-made plays" in the tradition of French writers such as Scribe and Sardou. The pinnacle of Maugham's popularity as a dramatist came early, in 1908, and caught even him by surprise: in that year four Maugham plays were running simultaneously in the West End - Lady Frederick, Jack Straw, Mrs. Dot and The Explorer - a feat that has never been surpassed. The plays of his maturity, however, are considered his best and are the most frequently revived, especially The Circle (1921) and The Constant Wife (1926).

Production History

The Constant Wife premiered on Broadway on November 29, 1926, in a production that ran for almost 300 performances and starred Ethel Barrymore (famously depicted the next year in The Royal Family). One of Maugham's favorite stories was of the first our-of-town preview of the play, when Barrymore had trouble with her lines, improvised badly, and even added lines from other plays. Furious, Maugham rushed backstage to confront her, but Barrymore deflated him by saying, "Oh darling, I've ruined your beautiful play, but it'll run a year." Added Maugham, "She had and it did!"

The London premiere came in April 1927, in a production that featured Fay Compton and ran for only 60 performances. The play’s failure resulted in part from a disastrous first night when a row of stall seats were mistakenly opened to the holders of pit tickets and chaos ensued. There was, however, another and more fundamental problem: the English audiences were simply not yet ready to accept Maugham's portrait of marriage and the role of the modern wife. London's leading theatre critic, James Agate, panned the play, and Herbert Farjeon, writing in The Graphic, questioned whether even Compton's glamour would "entirely blind audiences to the ethical questionability of her stage conduct."

The Constant Wife’s great success in the United States can in part be ascribed to societal climate. As the economic liberation of women was more advanced in America, both audiences and critics found the play's arguments more palatable - the critic Robert Benchley observed that it had "a great many lines of high comedy and not a few of wisdom." For many people, that wisdom gained more relevance in the feminist climate of the latter part of the twentieth century when, like A Doll's House, The Constant Wife was frequently revived on both sides of the Atlantic. Most notably, Ingrid Bergman played the lead in productions in both London and New York in the 1970's, and since 2005 the play has several new productions in the U.S., including a Broadway revival starring Kate Burton and Michael Cumpsty, plus a season long run at the Shaw Festival in Canada. It is perhaps not an exaggeration to say that the ideas in The Constant Wife were too advanced for Great Britain in the 1920's and that it took forty years for the play to find a truly responsive audience there.

Programme Notes

In his thirty-odd years as a successful playwright, Somerset Maugham's plays were mostly about two things: the middle or upper-middle class, and marriage. He believed that by studying the class system from the inside, and especially the marriage contract, fresh insight could be had on how men and women relied on its rules and regulations to guide their actions inside the patriarchal structure. In his early plays, it is the achieving of the marriage contract that drives the action. In his middle period it is the struggle to maintain the sanctity of marriage that the plots revolve around. And in his late period, including The Constant Wife, the marriage contract is revealed as an essentially flawed concept that binds women to a moral life that is foreign to their nature.

To Maugham, marriage is not religious and not romantic: it is social. It was a middle-class patriarchal construct, the purpose of which was to ward off the primal interactions of human folly and its resultant chaos, which lay just around the corner for any civilization. The fact that the marriage contract put all its power in the hands of men left its women in various stages of social imprisonment, both sexually and spiritually. Maugham's comedy takes a fresh look at Ibsen's A Doll's House, which had premiered in England only forty years before. Constance, like Nora, comes to see the bondage of her marriage as something to be resisted; but unlike Nora, Constance does not turn her back on marriage and home and family. She merely rearranges the nest's psychic furniture more to her liking.

Wry, witty, and with themes that are still very much with us, The Constant Wife is a comedic admonition to all those who rely on love and sentiment to ward off the lazy middle-class habit of infidelity.

Additional Notes

In The Constant Wife, written in 1926, Somerset Maugham shows a woman achieving financial independence by embarking on a new career in interior design. He did not have to go far to find a model for this transformation, as his soon-to-be-divorced wife Syrie Maugham was then on the verge of becoming London's most fashionable interior designer.

When the Maughams married in 1917, both had been married before (Syrie serially) and their daughter Liza was almost two years old. This marriage, too, quickly deteriorated. "It was a marriage of convenience on both sides," a friend said. "Willie knew about her past and her lovers, and Syrie knew about his homosexuality... The trouble was she fell in love." Maugham felt he had been pressured into getting married, resented her continued demands on him, and considered his ten years with her a misery. Syrie had always been interested in antiques and interior decoration, and in 1923, partly to console herself for another failing marriage, she opened a small shop in Baker Street. (Maugham was dismayed that his wife had "gone into trade," and described her dismissively as selling chamber-pots to millionairesses.)

The Maughams' story has odd parallels in The Constant Wife. Like the Middletons, Maugham was a doctor, Syrie an interior designer. But in their real life, it was the husband who went on extended travels with another man.

Though Somerset Maugham was a leading playwright in the theatres of London, New York and Paris from 1908 to 1933, he became convinced that prose drama was the most ephemeral of all the arts. In particular, he believed that plays of ideas - even those by Ibsen and Shaw – become museum pieces when social attitudes change and the ideas become familiar and accepted. "Now that everyone admits the right of a woman to her own personality," he claimed, "it is impossible to listen to A Doll's House without impatience." Looking at his own plays, Maugham gave them a performing life of about twenty years.

Maugham was forgetting, of course, that great plays of ideas are made up of much more than thesis and argument: they can be rich in character, brimming with wit, and fascinating in their construction. Moreover, if the play actually challenges its opening-night audiences with advanced social thinking, rather than simply mirroring the mores of its time, it will have a relevance and a life until that thinking becomes universally conventional.

So even today, certain vestigial aspects of the inequality between the sexes still cause this play to resonate with modern audiences.

Incidental Music for this production

The music chosen for this production is from a recording entitled Forgotten Dreams – Archives of Novelty Piano, 1920s-1930s, produced and performed by Dick Hyman and John Sheridan (Arbors Records).