The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

by Wm Shakespeare

George Hartpence as Brutus

directed by Steve Kazakoff

April 3-5, 1998

at The Kelsey Theater

on the campus of the Mercer County Community College

George Hartpence as Julius Caesar

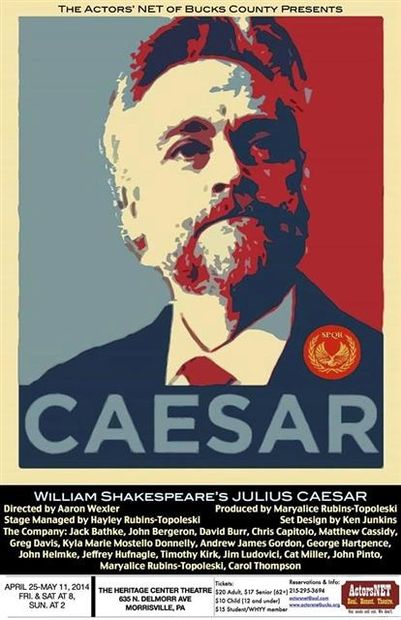

directed by Aaron Wexler

April 25 - May 11, 2014

at The ActorsNET

in the Heritage Center Theatre in Morrisville, PA

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar (2014)

by Wm Shakespeare

directed by Aaron Wexler

produced by Maryalice Rubins-Topoleski

stage management by Hayley Rubins-Topoleski

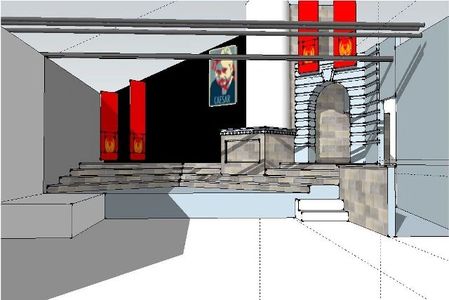

set design by Ken Junkins

lighting design by Andrena Wishnie

sound design by Aaron Wexler

at The ActorsNET of Bucks County

in The Heritage Center

Morrisville, PA

Critical Praise

Anthony Stoeckert writes for the Princeton Packet TimeOff entertainment section:

Mr. Hartpence’s Caesar is noble, and humble even though he’s clearly confident. He also shows real shock and hurt (not just physical hurt but the feeling of being betrayed) as he is murdered. The line “et tu Brute” is so clichéd, but Mr. Hartpence finds the truth in it.

Critical Praise

Wren Workman writes for STage Magazine:

George Hartpence (Julius Caesar) was very well cast, his Caesar was, charismatic, confident and commanding. He spoke with a cool and calming voice. Hartpence is a long time Shakespearean actor and it shows in all the best ways. In his moments on stage you can believe him to be the symbol of hope that Marc Antony speaks of.

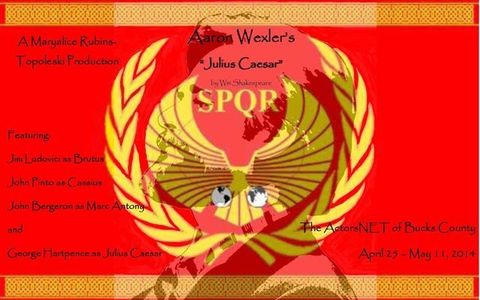

Promo Video for the ActorsNET production of JULIUS CAESAR

George Hartpence as Julius Caesar

Jim Ludovici as Marcus Brutus

John Bergeron as Marc Antony

John Pinto as Cassius

Dramatis Personae

JULIUS CAESAR - Part I - Caesar Lives

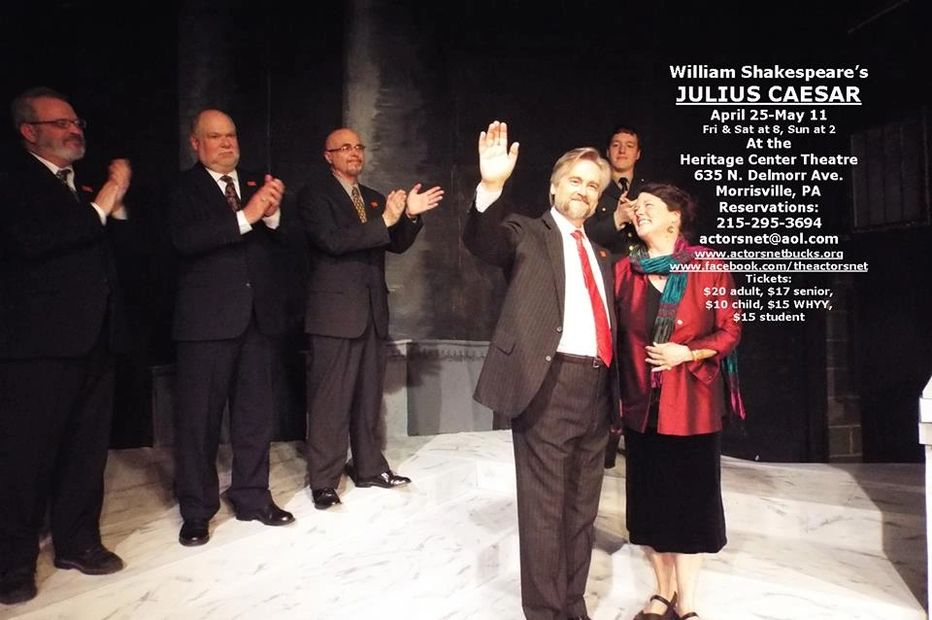

Caesar works the crowd: George Hartpence (foreground) as Julius Caesar & Carol Thompson as Calpurnia

Julius Caesar at ActorsNET

see the assassination scene from the ActorsNET production of Julius Caesar

JULIUS CAESAR - Part II - Great Caesar's Ghost

John Bergeron as Marc Antony - delivering Caesar's eulogy

"Nor heaven, nor earth hath been at peace tonight."

George Hartpence as Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar THE TIME AND PLACE

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar depicts Rome’s transition from a republic to an empire. According to ancient historians, the republic dates back to 509 B.C., when the last Roman king was expelled and two consuls shared control of Rome’s military. Each year a new pair of consuls had to be elected. The Senate was the republic’s most important political institution. It was composed of several hundred members of Rome’s leading families, who could serve for life. Two citizen assemblies made laws and elected Rome’s magistrates, including consuls. Although the Senate was supposed only to advise the magistrates and the assemblies, it actually held most of the power.

Over several centuries, Rome greatly expanded its territories in a series of foreign wars, but these conquests created internal tensions. Some politicians began to challenge the Senate’s authority. Often they gained support from disgruntled veterans and other neglected members of society. Beginning in 133 B.C., Rome was plagued by widespread corruption and civil warfare.

In 60 B.C., Rome came under the control of the wealthy politician Crassus and two military leaders, Julius Caesar and Pompey. This coalition was known as the First Triumvirate. In 53 B.C., Crassus received command of the armies of the East but was defeated and killed by the Parthians, and soon Pompey and Caesar were at odds with each other. After Pompey tried to strip Caesar of his powers in 49, Caesar crossed into Italy, forcing Pompey to flee. Pompey was killed the next year in Egypt. Caesar continued to meet resistance from Pompey’s sons. He finally defeated them in 45 and returned to Rome, where he had himself appointed dictator for life. Shakespeare’s play opens in 44 B.C., when it appeared that Caesar might topple the republic and reestablish a monarchy.

On February 15, 44 B.C. at the feast of Lupercalia, Caesar wore his purple garb for the first time in public. At the public festival, Antony offered him a diadem (symbol of the Hellenistic monarchs), but Caesar refused it, saying Jupiter alone is king of the Romans (possibly because he saw the people did not want him to accept the diadem, or possibly because he wanted to end once and for all the speculation that he was trying to become a king). Caesar was preparing to lead a military campaign against the Parthians, who had treacherously killed Crassus and taken the legionary eagles; he was due to leave on March 18. Although Caesar was apparently warned of some personal danger, he nevertheless refused a bodyguard.

On March 15th - 3 days before his scheduled departure for another long military campaign - Caesar attended the last meeting of the Senate before his departure, held at its temporary quarters in the portico of the theater built by Pompey the Great (the Curia, located in the Forum and the regular meeting house of the Senate, had been badly burned and was being rebuilt). The sixty conspirators, led by Marcus Junius Brutus, Gaius Cassius Longinus, Decimus Brutus Albinus, and Gaius Trebonius, came to the meeting with daggers concealed in their togas and struck Caesar at least 23 times as he stood at the base of Pompey's statue. Legend has it that Caesar said in Greek to Brutus, “You, too, my child?” After his death, all the senators fled, and three slaves carried his body home to Calpurnia several hours later. For several days there was a political vacuum, for the conspirators apparently had no long-range plan and, in a major blunder, did not immediately kill Mark Antony (apparently by the decision of Brutus). The conspirators had only a band of gladiators to back them up, while Antony had a whole legion, the keys to Caesar's money boxes, and Caesar's will.

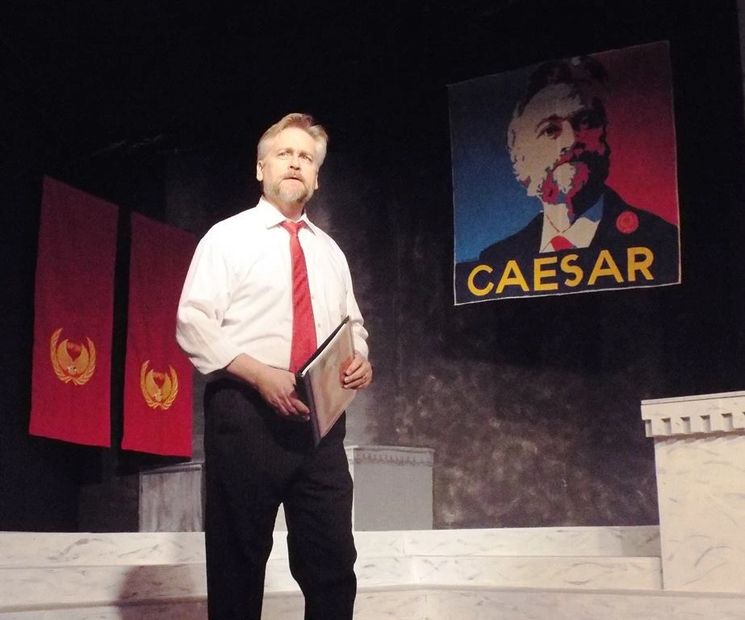

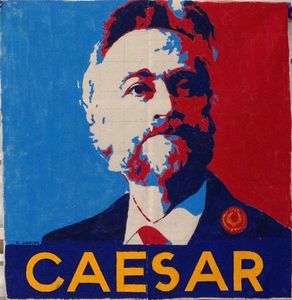

Caesar banner painted by Ken Junkins and designed to be torn down and ripped in half for each performance

The History of The Tragedy of Julius Caesar by Wm Shakespeare

Written around 1599, Julius Caesar is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. The play is based on historical events surrounding the conspiracy against the ancient Roman leader Julius Caesar (c.100-44B.C.) and the civil war that followed his death. Shakespeare portrays Caesar's assassination on the Ides of March (March 15) by a group of conspirators who feared the ambitious leader would turn the Roman Republic into a tyrannical monarchy.

Julius Caesar was most likely the first play performed at the Globe Theater. Shakespeare wrote the play around 1599, just after he had completed a series of English political histories. Like the history plays, Julius Caesar gives voice to some late-16th-century English political concerns. When Shakespeare wrote Caesar, it was pretty obvious that the 66-year-old Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) wasn't going to produce an heir to the throne, and her subjects were stressed out about what would happen upon the monarch's death. Would chaos ensue when Elizabeth died? Who would take the queen's place? Would the next monarch be a fit ruler or a tyrant? In other words, Julius Caesar asks its audience to think about the parallels between ancient Roman history and contemporary politics.

Shakespeare' s main source for the play is Plutarch's famous biography The Life of Julius Caesar, written in Greek in the 1st century and translated into English in 1579 by Sir Thomas North. This is no big surprise, since Shakespeare and his contemporaries were completely obsessed with Roman culture and politics. (In fact, Elizabethan schoolboys spent most of their time reading and translating ancient Roman and Greek literature.)

Today, along with Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar is often taught in 9th grade classrooms as an introduction to Shakespeare. The relatively straightforward language and simplicity of plot make it a good starting point for students new to 16th-century drama.

CAESAR set design by Ken Junkins

Director's Notes: Aaron Wexler (April 2014)

What is it about Shakespeare that keeps us coming back to him year after year, decade after decade, century after century?

It’s not simply the beauty of his poetry, though that remains an irreplaceable aspect of the Shakespearean experience. No, it’s the timelessness of his themes and subject matter, and the universality of his remarkably complex characters. Shakespeare tapped into a vein of human experience so rich that every subsequent generation has found something to relate to no matter how removed they are from his own time.

Only a few generations after Shakespeare’s death, theaters in England were adjusting their performances to account for the advent of the proscenium stage and the neo-classical approach to drama (which led to some questionable decisions - including altering some of the tragedies to give them happy endings!).

By the late 19th century, a desire for historical accuracy and verisimilitude led to Shakespeare’s plays being performed in Elizabethan garb, with elaborate sets that required scene changes so long that much of the text was cut to keep the performances from running too long.

In the early decades of the 20th century, theatre artists began to approach Shakespeare from a more contemporary perspective, updating the setting of his plays while retaining the language, to highlight the still-relevant themes within Shakespeare’s works.

A notable example of this is Orson Welles’ production of Julius Caesar in 1937 based on the Nazi rallies at Nuremberg. This aesthetic has become more and more popular so that these days it is rare to see Shakespeare performed in Elizabethan garb and the eye towards historical accuracy that was the fashion in Queen Victoria’s day.

Only a few years ago, the Royal Shakespeare Company itself produced an interpretation of Julius Caesar set in an African junta. With that in mind, we have chosen to set our production in a version of Rome that looks and feels very much like our contemporary Washington, DC.

The faces you see on our stage may be different than the faces you see on the news every day, but the themes of power, ambition, duty to one’s friends and one’s country, and the danger of a mob mentality remain as relevant today as they were 400 years ago. We are just the latest in a long line of artists interpreting these words.

Long after we’re gone, cultures and societies we can’t even dream of will be finding something of themselves here.

Shakespeare will outlive us all.

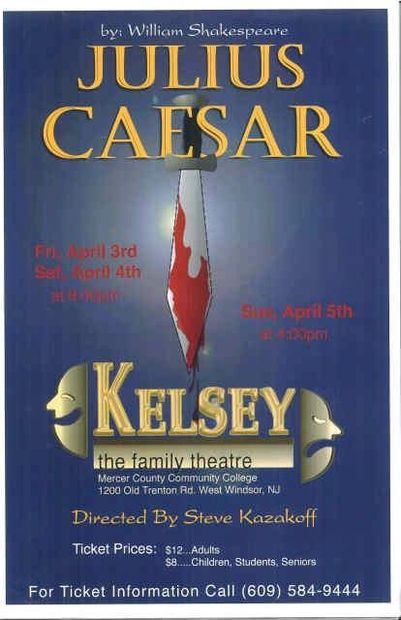

The Tragedy of JULIUS CAESAR (1998)

George Hartpence as Marcus Brutus

directed by Steve Kazakoff

April 3-5, 1998

at The Kelsey Theater

on the campus of the Mercer County Community College

Julius Caesar stills (1998)

George Hartpence (right) as Brutus & Erik Farber (left) as Marc Antony