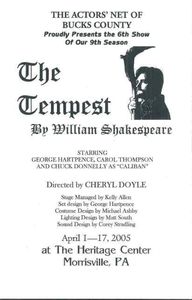

THE TEMPEST

by Wm Shakespeare

directed by Cheryl Doyle

set design by George Hartpence

April 1st through 17th, 2005

at The Heritage Center Morrisville, PA

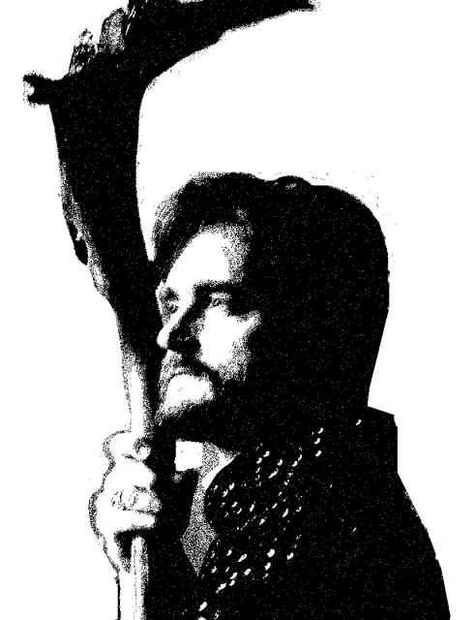

George Hartpence as Prospero - the right Duke of Milan

with

Carol Thompson as Ariel - a sprite

Kyla Marie Mostello as Miranda - daughter to Prospero

Jim Petro as Ferdinand - son to the King of Naples

Chuck Donnelly as Caliban - a savage

also featuring

C. Jameson Bradley as Gonzalo- an honest old Counsellor

John Shanken-Kaye as Alonzo- the King of Naples

Steve Lobis as Antonio - the usurping Duke of Milan

Aaron Wexler as Sebastian- brother to the King of Naples

Marco Newton as Trinculo - a Jester

Rupert Hinton as Stephano- a drunken Butler

including:

Tess Ammerman as Iris

Rachael Lavery as Juno

And as various creatures of the island, nymphs and sprites: Alex Bartlett, Gracie Coscia, Addy Coscia, Sommer Shanken-Kaye, Brenna Bajor, Arne Nelson, Scott Lutz, Carolyn Kelly, Danielle DiLorenzo and Haley Keister

Stuart Duncan writes for the Princeton Packet:

" You just plain aren't going to see a more charming and definitive production of The Tempest, probably in your lifetime. Don't miss it."

Ariel's "harpy" headpiece by:

Caroline (Cleo) Guyer at Cleo's Cave

Prospero's Staff custom designed by:

Mark Gaskins of Chigoe Creek Staffs

TEMPEST (2005) Photo Gallery

A BETTER WORLD

Program notes compiled for the ActorsNET production of Wm Shakespeare's The Tempest

above: George Hartpence (right) as Prospero with Kyla Mostello and Jim Petro as Miranda and Ferdinand.

Often seen as the playwright's farewell to the theatre world, Shakespeare’s The Tempest reveals a world of illusions and magic—where an angry sorcerer manipulates spirits and humans alike in his search for revenge. Banished to an abandoned island by his power-hungry brother, the Duke of Milan, Prospero seizes his opportunity for retribution in a powerful storm that shipwrecks the Duke and other nobles on the island. The story of a man who realizes that the sole way to regain his humanity is to relinquish his omnipotent control, The Tempest is a powerful tale that unites Shakespeare's celebrated themes of love, man's vulnerability and forgiveness.

The Tempest is usually listed among Shakespeare's Romances, those curious plays that critics cannot safely categorize as either comedy or tragedy - although if this play resembles any other of Shakespeare's, it is surely A Midsummer Night's Dream. In both, the manipulative power of magic is used with some mischief, but always with an eye toward setting the world to right, which indeed it seems to do in both plays. Why not call The Tempest a comedy, then? There is little overt suffering in this play. We are even given the happy union of a young couple of lovers, the hallmark of all of Shakespeare's lighter comedies. The magic of the island is a magic quite similar to the magic of the theatre itself. We, as the audience to Shakespeare and to Prospero, may be moved, frightened, awed, but are never really in any danger.

However, it is in this same magic, and the power it gives to Prospero, that the play's less comic elements emerge. For there is a darker mood to The Tempest that distinguishes it from Shakespeare's more playful works: at its heart, this is a story of revenge. Or perhaps, more aptly, a story about trying fiercely to avoid revenge. Shakespeare gives us every reason to expect a harsh comeuppance for those who betrayed Prospero, and certainly Prospero never suggests anything other than a vengeful anger toward them. His enemies are in his hands, and, all-powerful, he can do with them as he likes. It is a scenario ripe for a tragedy of revenge; despite the enchanted setting of the isle, full of "sweet airs, that give delight," a perfect setting for a fairy-tale comedy, Shakespeare has drawn us perilously close to the tragedy of a tyrant's wrath.

Of course, neither he nor Prospero ever quite succumb to that possibility. Nevertheless, we should keep that darker possibility in mind as we watch this play, even though Caliban’s cramps and Ferdinand’s unhappy chores appear to be the utmost of Prospero's cruelty. For a man with near omnipotence, he shows self-restraint in his governance, but the cliché of absolute power should not be forgotten, even as Prospero attempts to exercise justice with that power.

For it is justice, not revenge, which Prospero seeks in this play. His goal throughout is to reform, to improve, not simply to punish. Though he could easily resort to extreme measures in this goal, he refrains. And in refraining, he risks failure - he risks the refusal of those he encourages to better themselves. The ending of this play is one of troubled peace; Prospero's treacherous brother, Antonio, is forgiven, but shows no gratitude, no reconciliation, and no remorse. Ferdinand and Miranda seem destined for happiness; however, their sudden union - a love born largely out of the fact that her experience of the opposite sex is decidedly limited - might not support such optimism. And what of Caliban? He vows to "seek for grace," but from whom? Who knows what his future holds? The play concludes and yet it does not end - much is left undecided, and not all matters have been turned for the better.

But consider Prospero's alternative. To force a happy ending would be precisely the kind of tyranny he seems to try to avoid. Enforced virtue is not virtue; it is resentful obedience - the sullen conformity of Caliban confirms this. For these characters to reform truly, they must be left to do so of their own free will. And we, Shakespeare's audience, are no different. We cannot simply rely on the magic of the theatre to set us at our ease. We cannot allow its magic to point us toward a vision of the world as a place where problems and failures are solved by a wave of a wand. We may wish to - indeed, we may prefer the world of the theatre, with its spectacular pleasures and easy solutions - but Shakespeare is all too aware that such temptation is addictive, and directs us away from our true responsibilities as human beings.

And surely that is Shakespeare's goal here - to create a work that seeks to inspire, not awe. After centuries of deifying him, we have come to think that Shakespeare can do no wrong. The Tempest shows that the man himself would reject such an assessment. Like his on-stage equivalent, Prospero, he recognizes that his art has limits - and that it can lead his audience astray. Caliban, after all, is the product of Prospero's authority - first taught, then punished, then deluded by his master, he emerges as "a thing of darkness" that Prospero, in a moment of harsh self-judgment, must acknowledge as his own. Caliban, once his own king, is reduced to dreams of riches and to licking the boot of a drunken butler - a poor product of Prospero's tutelage. But left to his own devices, Caliban learns to discriminate between the substantial and the illusory - it is he, after all, who recognizes as "trash" the fine clothes Prospero lays out as bait for the comic conspirators, and who acknowledges his own folly by play's end. Such improvement, however small, is more substantial because it comes unforced.

If The Tempest is Shakespeare's farewell to the theatre - a final recognition of the limits of art's magic and of the need for its magicians to allow humanity to pursue its own course, either to wisdom or to folly - then it need not be a rueful farewell. For surely Prospero's mercy is an act of optimism, which springs from a belief that though human nature cannot be cured in an instant, it can be cured. If Shakespeare leaves us with this play, and abandons us to the real world, he does so in the hope that we, as much as Caliban, will seek to be wiser from now on. Despite its tone of finality, this play, more than any other of Shakespeare's, looks forward to a better world than the one found on a small desert island.

Sources:

The Tempest at the University of Utah web site: http://www.cc.utah.edu/~mp2434/325tem.html

David Kathman’s article on “Dating The Tempest” at The Shakespeare Authorship Page: http://www.shakespeareauthorship.com/tempest.html

Stephen Greenblatt, “Will In The World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare”, W.W. Norton & Company 2004

Marjorie Garber, “Shakespeare After All”, Pantheon, 2004

Virginia Mason Vaughan (Editor), Alden T. Vaughan (Editor) “The Tempest”, Arden Shakespeare 1999

THE TEMPEST (2005) at ActorsNET

Miranda beholds the shipwreck. Kyla Marie Mostello as Miranda & George Hartpence as Prospero

Critical Praise for THE TEMPEST (2005)

Stuart Duncan writes on April 13, 2005 for the Princeton Packet:

The current production of The Tempest at Actors' NET in Morrisville, Pa., is one of the best examples of what a truly dedicated company, armed with intelligence and imagination, can do with good material.

George Hartpence once again shows why he is a consummate Shakespearean performer — stunning diction, tempered with genuine emotion, so that every word is not only said and heard, but understood in context. One moment will suffice (and strangely, it's a moment I never felt before through several dozen different stagings by various companies). It comes late in the show, when Ferdinand already has claimed his Miranda and Prospero realizes that he may be gaining a son-in-law, but surely he is losing a daughter. It is an expression rather than a mere speech and it drives deep into the heart.

Carol Thompson is more than just a sprite; she is a whirlwind of joy, leaping around the stage in search of spells to cast.

You just plain aren't going to see a more charming and definitive production of The Tempest, probably in your lifetime. Don't miss it.

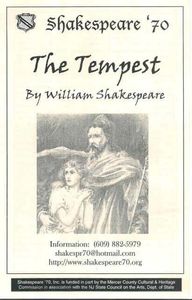

THE TEMPEST for Shakespeare`70 (2001)

George Hartpence (center) as King Alonzo

Shakespeare`70 production

June 7th - 16th, 2001

at the Washington Crossing Open Air Theater

directed by Frank Erath

featuring:

Dale Simon as Prospero

Steve Kazakoff as Caliban

Kay Potucek as Ariel

Shakespeare`70 "The Tempest" program cover

no other photos or production information available

THE TEMPEST (1999) for Villagers Theatre

George Hartpence as evil, uncle Antonio

October 15 - 23, 1999

directed by Ana Kalet

for Villagers Theatre in Somerset,NJ

Rob Pherson as Prospero

Catherine Rowe as Gonzala

Faith Agnew-Dowgin as Ariel

Amy Metroka as Miranda

Scott E Costine as Alonzo

Marc Scott as Caliban

Warren Lieuallen as Ferdinand

Jon Paradise as Sebastian

Chris Lowry as Stephano

Elizabeth A. Durkin as Trincula

Edward Gonzalez as the boatswain

Mallory Pherson as Ceres

Christine Havala as Iris

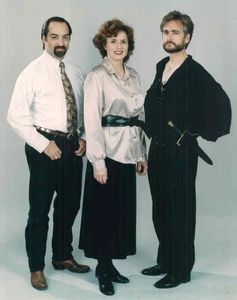

from left: Scott E. Costine as Alonzo, Catherine Pherson as "Gonzala" and George Hartpence as Antonio

cast photo

THE TEMPEST (1999) at Villagers Theatre

Prospero demands his dukedom of his brother. Rob Pherson (left) as Prospero, George Hartpence (center) as Antonio & Catherine Rowe (right) as Gonzala