A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS by Robert Bolt

role: Sir Thomas More

October 26 - November 11, 2012

at The Heritage Center

635 N. Delmorr Ave

Morrisville, PA

directed by Cheryl Doyle

staged by George Hartpence

stage manager - Hayley Rubins-Topoleski

set design - George Hartpence

lighting design - Andrena Wishnie

costume and sound design - Cheryl Doyle

Additional technical credits:

Set Construction: Lead Carpenter - John Helmke

Ass't Carpentry - Hugh Barton

Scenic Artist - Dale Simon

Additional Set Painting - Maryalice and Hayley Rubens-Topoleski

Sound Operator - Isaiah Davis

Costume Assistance - Vera Kunte, Fran Wilcox, Kyla Mostello Donnelly, Alice Topoleski

George Hartpence as Sir Thomas More

The title of the play reflects 20th century agnostic playwright Robert Bolt’s portrayal of More as the ultimate man of conscience. As one who remains true to himself and his beliefs under all circumstances and at all times, despite external pressure or influence, More represents "a man for all seasons." Bolt borrowed the title from Robert Whittington, a contemporary of More, who in 1520 wrote of him:

"More is a man of an angel's wit and singular learning. I know not his fellow. For where is the man of that gentleness, lowliness and affability? And, as time requireth, a man of marvelous mirth and pastimes, and sometime of as sad gravity. A man for all seasons."

Maryalice Rubins-Topoleski as Margaret More and James Banar as King Henry VIII

SETTING

A Man for All Seasons is set in the Reformation Period of Britain. The time was also considered to be part of the Renaissance. The time was from 1529 through 1535. It was during the reign of King Henry VIII, the second Tudor King of England (reigned 1509-1547).

The Sixteenth Century (the 1500’s) was an exciting time. Much was happening. The world, including Britain, was changing quickly. People were thinking and sharing new ideas. Examples of this sharing were the visits Erasmus, a Dutch humanist and writer, made to Sir Thomas More. Johannes Gutenberg had invented the printing press around 1450. Christopher Columbus had reached America in 1492. Michelangelo was still alive. Leonardo DaVinci had died in 1519.

Sir Thomas More's residence, where some of the action takes place, was in Chelsea. Chelsea is a district of London. Hampton Court, where other action takes place was the king’s residence. It too is in the area of London, on a bend of the Thames River.

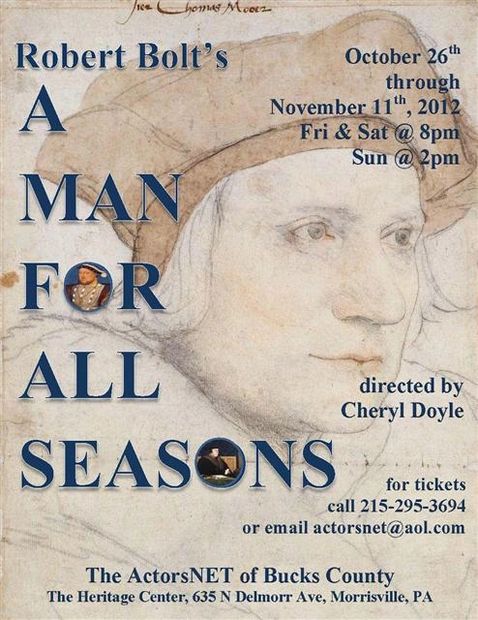

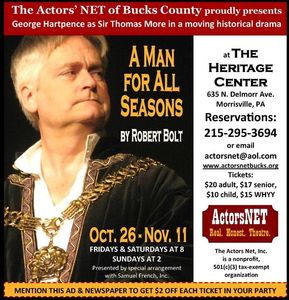

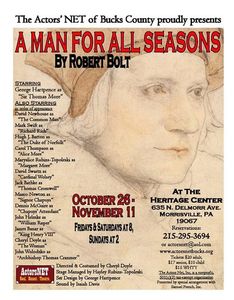

A Man For All Seasons posters and ads

preliminary poster

ad for local papers

final ActorsNET poster

Dramatis Personae

A Man For All Seasons - set design by George Hartpence

A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS - Act I

George Hartpence as Sir Thomas More

A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS - Character List

Sir Thomas More - The protagonist of the play. More’s historical refusal to swear to Parliament’s Act of Supremacy is the play’s main subject, but Bolt intentionally does not depict More as the saint or martyr of legend. Bolt does not see More as a person who takes a stand and sacrifices himself for a cause. Rather, Bolt’s More is a man who gives up his life because he cannot sacrifice his own commitment to his conscience, which dictates that he not turn his back on what he believes is right or on God. To More, a man’s conscience is his self, so he refuses to betray his own conscience even on pain of death. Significantly, More makes no move to speak out against King Henry’s divorce or to make any public gesture that indicates his opinion on the matter. Only after Cromwell condemns him does Thomas reveal his true opinions.

The Common Man - The Common Man sporadically narrates the play, and he plays the roles of most of the lower-class characters: More’s steward Matthew, the boatman, the publican (innkeeper), the jailer, the jury foreman, and the headsman (executioner). Bolt explains in his preface that he intends the Common Man to personify attitudes and actions that are common to everyone, but ultimately the Common Man shows that by common, Bolt implies base. In most instances, the Common Man plays characters who just do their jobs without thinking about the consequences of their actions or anyone’s interest other than their own. Therefore, most of these characters end up betraying their own personal moral values. Over the course of the play, the characters the Common Man plays become more and more guilt-ridden. In the end, the Common Man silences his guilty conscience by finding solace in the fact that he is alive. He ends the play by implying that most people do the same thing.

When he is not in a separate character, the Common Man helps set the scene for the audience. He talks to the audience directly.

Characters played by the Common Man

- Matthew, the Steward

Matthew is the Common Man character that makes the most appearances. He understands his position well. He knows what he should do, what he can do, what he should not do and what he is not required to do. What he should do is the work that is required by his position in the More household. What he can do is pass on unimportant information about his employer, Sir Thomas. What he should not do is pass on secret information about Sir Thomas. What he is not required to do is alert his employer that people are making enquiries about him. He also knows that he is not very important in the eyes of his employer, who has a tendency not to see him.

- Boatman

The boatman is mainly concerned with making a living. More tends to not see him; similar to the way that he does not see Matthew, the steward.

Publican

The publican, who runs a tavern or pub called “The Loyal Subject,” is willing to overlook suspicious activity with the expectation that he will be making some money by serving those involved. He is not a spy, as some people who actually are spies believe he is, but rather he is just trying to make a living.

- Jailer

The jailer is used as a witness to trap Sir Thomas. Then, an attempt is made to use him as a paid spy in an attempt to get information on Sir Thomas. The offer of money frightens the jailer, whose main concern now is keeping out of trouble and staying alive.

- Jury Foreman

The jury foreman is reluctant to take part in the trial of Sir Thomas. No good will come of it. But, he doesn’t have a choice. And, when the time comes to give the verdict, he does what is necessary to insure his safety; he says that Sir Thomas is guilty.

- Headsman

The headsman has only one line. By the time he does his job, we can easily guess why he beheads Sir Thomas. It is the way that he can save his own self.

Richard Rich - A low-level functionary whom More helped establish. Rich seeks to gain employment, but More denies him a high-ranking position and suggests that Rich become a teacher. Rich, however, goes to work for Norfolk instead and eventually obtains from Cromwell a post as the attorney general for Wales in exchange for perjuring himself at More’s trial. Like the Common Man, Rich serves as a foil, or character contrast, for Sir Thomas. In particular, Rich’s meteoric rise to wealth and power is simultaneous with More’s fall from favor. Unlike More, Rich conquers and destroys his conscience rather than obeying it. The repetition of the word rich in his name signals Rich’s Machiavellian willingness to sacrifice his moral standards for wealth and status.

Duke of Norfolk - More’s close friend. Norfolk is ultimately asked by Cromwell, and even encouraged by More himself, to betray his friendship with More. A large and rather simpleminded man, he is often too stupid to know what’s going on, and he is innocent relative to Cromwell.

Alice More - More’s wife. A conflicted character, Alice spends most of the play questioning why her husband refuses to give in to the king’s wishes. Her attitude shifts from anger to confusion. Eventually, More shows her that he cannot go to his death until he knows that she understands his decision. When she visits her husband in prison, Alice finally shows him unconditional love, saying that the fact that “God knows why” More must die is good enough for her.

Thomas Cromwell - A crafty lawyer who is the primary agent plotting against More. Whereas Rich and the Common Man are driven to their immoral actions (conspiracy, execution, and so on) somewhat reluctantly at times, Cromwell is motivated more by an evil nature. He facilitates More’s downfall with only a minimum of guilt.

Cardinal Wolsey - The Lord Chancellor of England, who dies suddenly following his inability to obtain a dispensation from the pope that would annul King Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon and permit him to marry Anne Boleyn. Though Bolt’s character descriptions claim Wolsey is ambitious and intelligent, Wolsey’s character is not well developed, and his primary function relates to the plot. Wolsey’s sudden death hangs over the rest of the play as a warning to anyone who would court the king’s disapproval.

Chapuys - The Spanish ambassador to England. Chapuys is loyal to his country and intent on assuring that the divorce between King Henry and Catherine, which would dishonor Catherine, does not go through. When questioning More, Chapuys displays his aptitude for hiding his political agenda under the guise of religious fervor.

William Roper - An overzealous young man who is a staunch Lutheran at the beginning of the play and later converts to Catholicism. Roper is also Margaret’s boyfriend and, after he converts to Catholicism, her husband. Roper’s high-minded ideals contrast with More’s level-headed morality, making Roper yet another foil for More. Each of Roper’s scenes shows him taking a public stance on a new issue, in opposition to More, who prefers to keep his opinions to himself. In a conversation with Roper, More argues that high-minded ideals, which he dubs “seagoing principles” are inconsistent at best, and he advocates human law as a better guide to morality.

Margaret Roper - More’s well-educated and inquisitive daughter. Also called Meg, Margaret is in love with and later marries William Roper. She shows that she understands her father perhaps better than anyone else in the play (except for More himself, of course). However, like her mother, Margaret questions her father’s actions.

King Henry VIII - The king of England, who only briefly appears onstage but is a constant presence in the speech and the thoughts of the other characters. It is very important to Henry that others think of him as a moral person, and he therefore cares greatly about what More, a man of great moral repute, thinks of him. Henry, who believes that he can force everyone, including the pope, into validating his desires, wants to put his conscience at ease by forcing More to sanction the king’s divorce from Catherine.

Woman (Catherine Anger) - The character referred to as Woman is given the name Catherine Anger. She is the person who tried to bribe Sir Thomas More with a silver cup causing him to want to get rid of it immediately. He gives the cup to Richard Rich. Later the cup and the woman are back in the action when Cromwell tries to use them to trap Sir Thomas. Finally, as More is walking toward the headsman, the woman tries to get More to say that she was right.

Attendant of Chapuys - The attendant of Chapuys appears to have a lot in common with the Common Man characters. He is basically someone to whom Chapuys can speak his mind.

Cranmer - Thomas Cranmer was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 1533 because King Henry VIII liked the course of action that he promoted to assure that the King succeeded in divorcing Queen Catherine. He served the King even when what he was asked to do revolted him. Later, after the time period of this play, he was the force behind the creation of the Book of Common Prayer.

George Hartpence a Sir Thomas More & James Banar as King Henry VIII

David Swartz as Cardinal Wolsey & George Hartpence as Sir Thomas More

A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS - Act II

Memorable Quotes from A Man For All Seasons

George Hartpence as Sir Thomas More

The Duke of Norfolk: Oh confound all this. I'm not a scholar, I don't know whether the marriage was lawful or not but dammit, Thomas, look at these names! Why can't you do as I did and come with us, for fellowship!

Sir Thomas More: And when we stand before God, and you are sent to Paradise for doing your conscience, and I am sent to hell for not doing mine, will you come with me, for fellowship?

Cromwell: Now, Sir Thomas, you stand on your silence.

Sir Thomas More: I do.

Cromwell: But, gentlemen of the jury, there are many kinds of silence. Consider first the silence of a man who is dead. Let us suppose we go into the room where he is laid out, and we listen: what do we hear? Silence. What does it betoken, this silence? Nothing; this is silence pure and simple. But let us take another case. Suppose I were to take a dagger from my sleeve and make to kill the prisoner with it; and my lordships there, instead of crying out for me to stop, maintained their silence. That would betoken! It would betoken a willingness that I should do it, and under the law, they will be guilty with me. So silence can, according to the circumstances, speak! Let us consider now the circumstances of the prisoner's silence. The oath was put to loyal subjects up and down the country, and they all declared His Grace's title to be just and good. But when it came to the prisoner, he refused! He calls this silence. Yet is there a man in this court - is there a man in this country! - who does not know Sir Thomas More's opinion of this title?

Crowd in court gallery: No!

Cromwell: Yet how can this be? Because this silence betokened, nay, this silence was, not silence at all, but most eloquent denial!

Sir Thomas More: Not so. Not so, Master Secretary. The maxim is "Qui tacet consentire": the maxim of the law is "Silence gives consent". If therefore you wish to construe what my silence betokened, you must construe that I consented, not that I denied.

Cromwell: Is that in fact what the world construes from it? Do you pretend that is what you wish the world to construe from it?

Sir Thomas More: The world must construe according to its wits; this court must construe according to the law.

William Roper: So, now you give the Devil the benefit of law!

Sir Thomas More: Yes! What would you do? Cut a great road through the law to get after the Devil?

William Roper: Yes, I'd cut down every law in England to do that!

Sir Thomas More: Oh? And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned 'round on you, where would you hide, Roper, the laws all being flat? This country is planted thick with laws, from coast to coast, Man's laws, not God's! And if you cut them down, and you're just the man to do it, do you really think you could stand upright in the winds that would blow then? Yes, I'd give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety's sake!

Sir Thomas More: I think that when statesmen forsake their own private conscience for the sake of their public duties, they lead their country by a short route to chaos.

Sir Thomas More: I trust I make myself obscure.

Sir Thomas More: Why Richard, it profits a man nothing to give his soul for the whole world... but for Wales?

Sir Thomas More: Listen, Meg, God made the angels to show Him splendor, as He made animals for innocence and plants for their simplicity. But Man He made to serve Him wittily, in the tangle of his mind. If He suffers us to come to such a case that there is no escaping, then we may stand to our tackle as best we can, and, yes, Will, then we can clamor like champions, if we have the spittle for it. But it's God's part, not our own, to bring ourselves to such a pass. Our natural business lies in escaping. So let's get home and study this bill. If I can take the oath, I will.

Cardinal Wolsey: You're a constant regret to me, Thomas. If you could just see facts flat-on, without that horrible moral squint... With a little common sense you could have made a statesman.

George Hartpence as Sir Thomas More & Carol Thompson as Alice More

George Hartpence as Sir Thomas More & Maryalice Rubins-Topoleski as Meg More